The multitude of paintings that make up “ASA7BY,” Hany Rashed’s current exhibition at Mashrabia Gallery, may appear at first glance crudely painted and repetitive. Pencil lines are visible under the paint, and the limited palette consists of colors that look like they’re straight from the tube.

Backgrounds are plain blocks of color, there’s no attempt at depth and the same figures and faces appear over and over again. There doesn’t seem to be any sign of the artist delighting in the medium, and beauty doesn’t really come into it.

But as you go around the show, you realize these elements come together to form an overall style that directly correlates to the subject matter Rashed is tackling here, to great effect.

“ASA7BY” is the name of an Egyptian Facebook humor page, a rather inferior one that is famous for the abuse of visual Internet memes — funny images that spread virally and get reused in multiple contexts. The page is part of the boom in humor and politics on the Internet since the 25 January revolution began last year.

Rashed uses the same memes and their do-it-yourself aesthetic to reflect the post-uprising climate, the rollercoaster ride of hopes and tragedies, the discussions and absurdities. His apparently unmixed colors reflect the RGB of computer screens. The repetitiveness is reminiscent of the revolution’s crowds. This lo-fi style is combined with the artist’s ability to paint very evocative facial expressions.

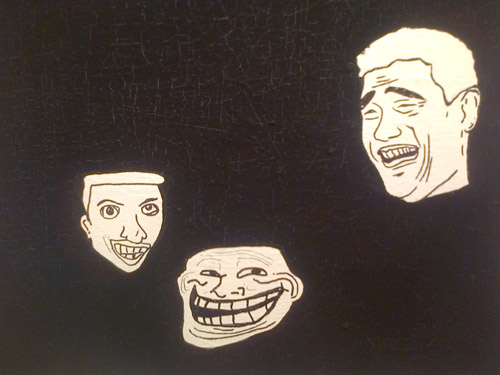

In one small painting, three monochrome meme faces float on a background of cracking black paint. Yao Ming, the Chinese basketball player whose laughing face has become associated with insensitivity and bad humor, is guffawing in a slightly embarrassed way. The blob-like Broblem meme has a mischievous smile, like he’s been caught in the act.

The Atef meme, representing underprivileged and rowdy Egyptian youth, has an excited, breathless look. The painting is titled “No Electricity,” and for some reason, without seeming to mean anything specific, it’s laugh-out-loud funny.

In “Okasha,” which must be named after rabid talk show host Tawfiq Okasha, two small people ride a large cockerel that has Yao Ming’s smiley head and, on its painterly body, the words “GO HOME.”

In “Passport,” the most cartoonish painting in the show, two figures are posed and painted in a way which suggests an old-fashioned, classic double portrait, but their heads are mask-like, black-and-white meme faces. An angry-looking one says (in Arabic): “It’s true that my mum has an American passport, but she’s not American.”

The other, sitting down, looks glumly at the floor. Is that Salafi leader Hazem Salah Abu Ismail’s mother? It’s not really clear, and that playful, undogmatic ambiguity — a sense of wonder that can be shared by the painter and his audience — characterizes the show.

Rashed has turned jokes from the Internet that are very obvious into small paintings that are vague, weird and dark, but still funny.

In a couple of larger paintings, though, which tend to be more carefully painted, the absurdity remains but the humor is gone. In “The Port Said Massacre,” faceless figures float above a green void and a curve of Toshiba, Coca Cola and Juhayna signs, beyond which is a gray void. The figures face every which way and variously seem to represent policemen, footballers, security guards and fans. On top are splatters of streaky paint.

The figures look like they are caught up in some bigger, messy game.

In “Traffic Officers,” faceless police officers float around, this time forming a more regular pattern on an orange void, but they are all almost identical, and in the same pose. There is a contrast between elements that look like they are copied from a photograph — the awkward pose and the rough, apparently traced outlines — and the figures’ cartoonish proportions. You wouldn’t keep that artificial look in a painting unless you wanted it there.

Many little groups abound in the paintings. There definitely seems to be an anti-political Islam vibe, but rather than a phobic fear of it, this is lighthearted, fun-poking criticism.

In one, a meme-like Mohamed Morsy is depicted as Napoleon on a horse (perhaps more relevant this week than when it was made). “Asahby is haram anyway,” says another, a phrase which has itself become a meme since a sheikh said the same of football after the Port Said stadium massacre.

“I’m not Brotherhood,” says the top of Yao Ming’s head in a third picture — another meme phrase echoing people who defend the Muslim Brotherhood at great length on social media sites and at the end put “by the way, I’m not Brotherhood.”

Hany Rashed has made an exhibition about a particular small corner of the Internet. It’s quite a brave thing to make a painting show about so specific a phenomenon, especially something that could be dismissed as silly, and to do so in a style that could almost be dismissed as doodling.

The paintings in “ASA7BY” are local and topical enough that many might not have universal appeal — it seems the artist has been deliberately focusing on communicating with young people in Egypt. The enigmatic and expressive qualities in some, however, create a surreal, evocative magic that may even hold the attention of the uninitiated.