If you piled up all the books that feature one-dimensional Islamist characters, you would have a veritable mountain of thrillers, detective novels, faux memoirs and pop political science. As you climbed toward the summit, you would find that in most of them Islamist is synonymous with a “bad-guy terrorist” who is also backwards, unenlightened, fanatical and violent.

A second stack of literature would be dwarfed beside it: In this smaller pile, you’d find books that render complex portraits of the men and women allied with political Islam. These books give Islamist characters varied backgrounds and fully human traits.

The more complex books do exist, and are perhaps developing into a literary subgenre. Islamism has been a recurring theme in books shortlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction: Syrian novelist Fawwaz Haddad’s “God’s Soldiers,” shortlisted in 2010, portrays Islamists without easy judgment; Islamists also appeared in Egyptian novelist Khaled al-Berry’s “Middle Eastern Dance,” shortlisted in 2011, and in Moroccan writer Mohammed Achaari’s “The Arch and the Butterfly,” 2011’s co-winner.

But these are still the minority. Most popular portrayals of Islamism in Egyptian fiction and film have been caricatures. Abir Hamdar, who helped organize the “Islamism in Arab Fiction and Film” conference earlier this year, noted, “some sources indicate that the films [about Islamism] were part of a larger strategy by the then-Mubarak regime in the early nineties to crack down on Islamists in the country and to mobilize the public against them.”

Books have generally had an easier time with government censors. However, Hamdar said that she and other project organizers noticed that the number of Egyptian films that dealt with Islamism “was far larger than novels and short stories.”

Nonetheless, there is Egyptian literature that looks beyond the long-beard-and-short-gallabeya stereotype.

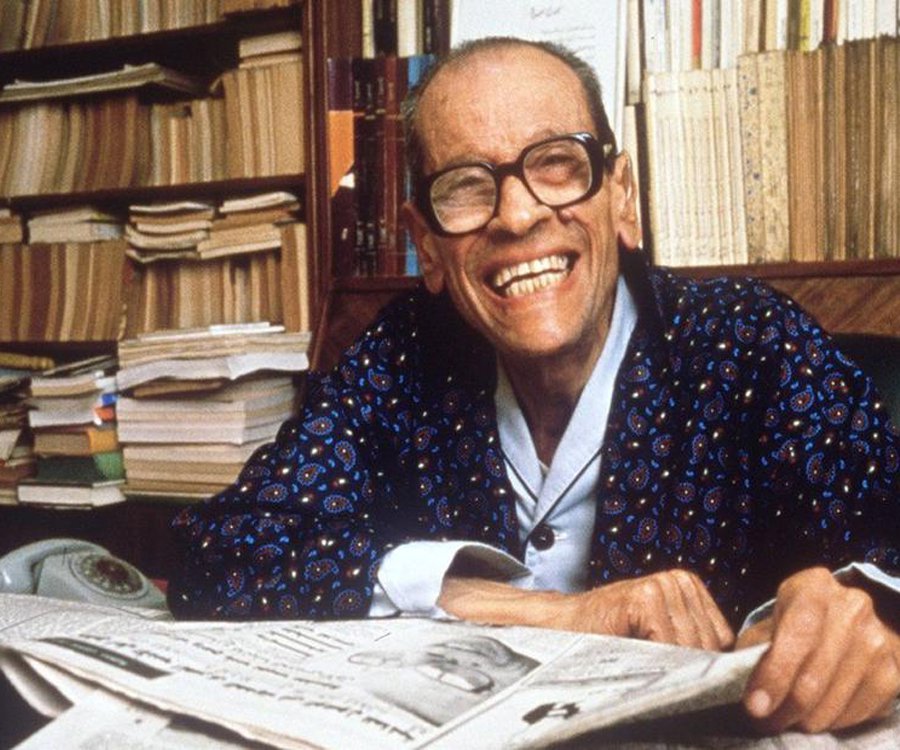

‘Mirrors’, Naguib Mahfouz, trans. Roger Allen. 1999

Mahfouz’s semi-autobiographical novel, “Mirrors,” is set in mid-century Cairo and was originally published in 1972. The book features a character modeled after Egypt’s leading Islamist thinker of the 1950s and 60s, Sayyed Qutb. The portrait, although often regarded as critical, also has sympathetic warmth to it. It opens: “Today he is a legend, and as a legend, interpretations vary.” It continues: “Although he always showed me generous fraternity, I was never comfortable with his face or the look in his bulging, serious eyes.”

Later, when the character refuses to review work by a Coptic writer, the narrator asks if he has become a fanatic. The character modeled after Qutb says: "Don't threaten me with clichés, they don't move me.”

Mahfouz also discusses political Islam in his memoir, “Naguib Mahfouz at Sidi Gaber: Reflections of a Nobel laureate, 1994-2001.” In 1995, a year after he was stabbed in the neck by a young Islamist, Mahfouz wrote, “The crisis of Islam and modernity – what to do? We must raise living standards and facilitate greater political participation, which means nurturing a greater democracy. We must allow anybody to form a political party. It is, after all, the people who must decide.”

‘Moon over Samarqand’, Mohamed Mansi Qandil, trans. Jennifer Peterson. 2009

Sayyed Qutb is portrayed quite differently in Qandil’s varied and wonderful “Moon over Samarqand”, which originally appeared in 2005. The novel follows a number of different characters, both in Uzbekistan and in Egypt, who are fired by the desire to institute political Islam. It is set during the period before Qutb’s execution by former President Gamal Abdel Nasser.

In “Moon”, political Islam has both ups and downs, particularly in its complicated dance with power. But Qutb’s character is warm and charismatic: “Endless rings of people of all colors encircled him, shaking his hand, kissing him, and taking him into their embrace. One wave after another – Africans and Asians, Baskhirs and Bosnians. He was at the center of them all. The sheikhs of Al-Azhar stood by, impotent, sensing that the rhythm of the conference had slipped through their fingers.”

‘A Child from the Village’, Sayyed Qutb, trans. Dr. John Calvert and William E. Shepard. 2004

Although “A Child from the Village” was written just prior to Qutb's conversion to the Islamist flag, it highlights the social and political concerns that underpin his philosophy.

Other interesting autobiographical works by Islamists include “My Journey with the Muslim Sisters”, by Fatma Abdel-Hadi (2011), published by Dar al-Shorouk.

'Live is More Beautiful than Paradise', Khaled al-Berry, trans. Humphrey Davies. 2009

Khaled al-Berry’s memoir, “Life is More Beautiful than Paradise,” takes place two decades after Qutb’s execution. It opens when Berry is 14 and is discussing local Islamists with his peers. Parroting his father, Berry says that “Abdel Nasser understood them and imprisoned them. If he’d let them alone, they’d have killed him the way they did [former president Anwar] Sadat.”

A friend who is affiliated with the Jama’a al-Islamiya reproaches Berry for condemning those who he doesn’t know. This friend portrays the Jama’a al-Islamiya as heroes defying a corrupt government. The friend has seen Berry shy from a fight, and promises to make him a gift of a bicycle chain. Berry writes: “I spent the night dreaming of the bicycle chain, just the way I used to dream that I was Bruce Lee, after seeing a movie of his, or Muhammad Ali Clay, after seeing a movie about him.”

Slowly, the adolescent Berry is drawn into the world of political Islam, until he is eventually a leader in the group, is imprisoned, and then finds his way out again.

‘The Smiles of Saints’, Ibrahim Farghali, trans. Andy Smart and Nadia Fouda-Smart. 2007

Ibrahim Farghali’s “The Smiles of Saints” sheds a fictional light of some of the same themes that animate “Life is More Beautiful than Paradise.” The narrator, Hanin, is raised abroad and returns to Egypt, where she is given her father Rami’s notebooks. The young Rami was active in the Islamist movement, but after Sadat’s assassination he withdrew into literature.

The book is complicated by more unusual aspects: Hanin has a Jewish lover who wants her to move to Israel. But this complication also helps to reveal the boundaries that surround and define us.

Critic Rasheed al-Enany has said that “No Arabic writer can really write about religion.” But some writers are certainly making the attempt to raise real questions about the intersection between politics, conscience and religious belief.