The years I worked as a translator were some of the most frustrating of my career. I would often spend hours upon hours looking up a single word. From one dictionary to the next, I would try to guess which synonym best communicated the author’s intentions. Having resolved the lexical issues in the text, I would then turn to the syntactical dilemma of making each sentence sound like it was originally written in the target language, not awkwardly put together.

When laboring studiously on an incomprehensible text or trying to gracefully break up a paragraph-long sentence, I often thought of myself as “The Unknown Soldier” whose efforts were going unnoticed. I hoped that these efforts would be revealed in due time; I pictured myself receiving a newly-founded Nobel Prize in Translation, for choosing the perfect synonym and breaking up the sentence flawlessly. Since I was translating newspaper articles at the time, the award hasn’t arrived — at least not yet.

But last week it was raining recognition for translators, not in the form of a Nobel Prize for myself, but rather when Sinan Antoon received the 2012 National Translation Award for his translation of Mahmoud Darwish’s “In the Presence of Absence.” Then later in the same week, the American University in Cairo’s Center for Translation Studies jumpstarted its celebration of the Translator’s Day (15 October, coinciding with the birthday of the founder of Egypt’s first house of translation Rifaa Tahtawi) with a lecture by Randa Abou-Bakr, Professor of English Literature at Cairo University. The lecture was entitled “Translating Poetry in the Age of Prose.”

Abou-Bakr is a brilliant scholar and translator, not only because she was one of my favorite professors as an undergraduate student, but her work speaks volumes about her experience with and passion for poetry, translation and literature in general. She has authored “The Conflict of Voices in the Poetry of Dennis Brutus and Mahmoud Darwish” and translated Ahmed Bekheit’s “Leila the Honey of Solitude.”

The two main questions Abou-Bakr tackled during her talk were, “Is translating poetry at all possible” and, “Why does translating poetry matter?” Although American poet Robert Frost once said, “Poetry is what gets lost in translation,” Abou-Bakr tells us that theoreticians have suggested several strategies to deal with the multi-layered nature of poetry in ways that are both meaningful and beautiful. One way is to prioritize and centralize one of its elements over the others; for example, the sounds, the meaning, or the meter. Others believe in approximating: adopting an approach of dealing with a large variety of elements all at once. Abou-Bakr however, subscribes to another school of translation, namely focusing on the emotional resonance of the poem.

“I like to keep my translations as close as possible to the originals in the sense that I do not try to be a poet on my own, but rather claim to myself that I am the prophet who has received a certain revelation — not a message — and I am now being trusted with the sacred task of transmitting it to others.” The smooth flow and rhythm of Brutus' original South African poem was indeed retained in Abou-Bakr’s translation into Arabic, which she shared with the audience.

As for the second question of why translating poetry matters, in order to answer it, Abou-Bakr had to explain why literary translation matters in the first place. Translation of literature, she argued, was “one of the most fertile areas of cultural exchanges: it is a tool for understanding how cultures are interconnected as well as fragmented.” The act of translation itself can manifest the dynamics between two cultures, such as when a translator chooses to either domesticate or exoticize the text as she renders it into the target language.

Abou-Bakr noted that literary translation remains focused on the novel, which is considered by critics to be the modern epic of the middle class, as well as being an archive of a nation’s everyday life and customs, although it is now being rivaled by other prose forms: the blog, the Facebook note and the tweet, as Abou-Bakr mentioned. But more importantly, there has been a surge in the production of Egyptian poetry recently, particularly colloquial poetry, with the January 2011 revolution.

Poets such as Fouad Hadad, Naguib Sorour, Ahmed Fouad Negm. Abdel Rahman Elabnoudy, and Tamim Elbarghouti have produced works whose language with its close proximity to that of everyday life has allied itself with ordinary people.

Translating this kind of poetry becomes important because it completes the archive of a people which is begun with the novel and also, as Abou-Bakr indicates, “it would be an extremely rich reflection of today’s social, political and cultural transformations in Egypt and the region. Making Egyptian colloquial poetry available in translation would introduce the genre to a world audience and at the same time contribute to the reconstruction of a more diverse canon of modern Arabic literature in world academic institutions.”

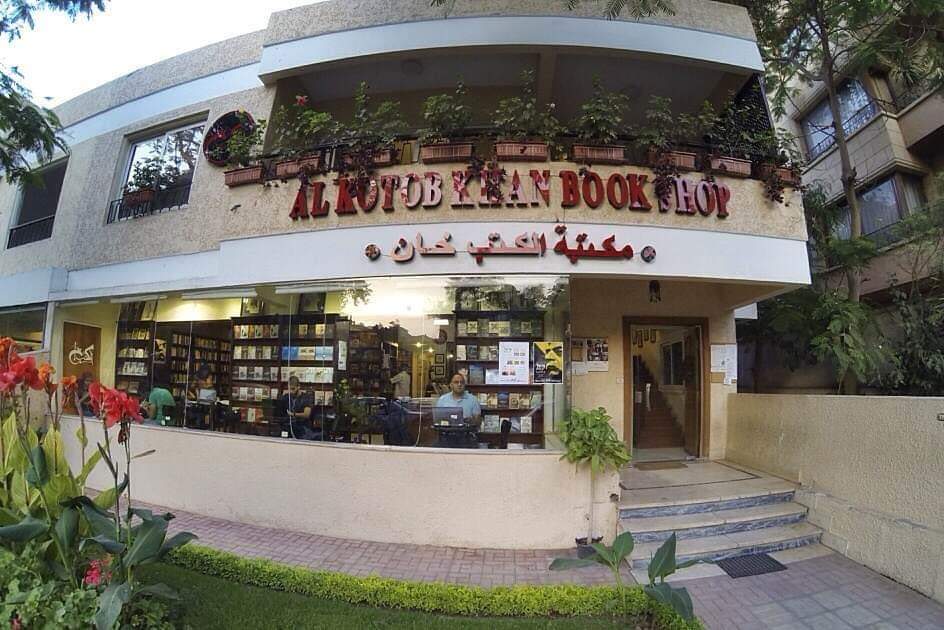

Poetry is indeed a neglected genre as Abou-Bakr indicated, not in translation, but also in publishing to begin with. Perhaps the new niches coming up, such as Jadaliyya — where Abou-Bakr has published her translated poems — can be the answer until publishing houses and academic institutions decide to pay more attention to it.

In the meantime, I am still waiting for my award.

The Center for Translation Studies is holding another lecture on the occasion of The Translator’s Day, the first in the AUC New Cairo Interdisciplinary Series entitled “Sharia Translated” by Dr. Amr Shalakany at the New Cairo Campus on Sunday at 1 pm.