By Schneider, Anna-Sophie for Spiegel Online

Marcella Hansch is afraid of fish, but she loves diving nonetheless. When fish swim toward her, she begins to breathe more quickly, causing her oxygen tank to deplete rapidly. But during a 2013 dive in Cape Verde it wasn’t a fish that alarmed her but a plastic bag. This startle led Hansch (who was studying architecture in Aachen) to come up with an idea for her university thesis project – a concept that could ultimately solve one of our planet’s biggest environmental problems: plastic pollution.

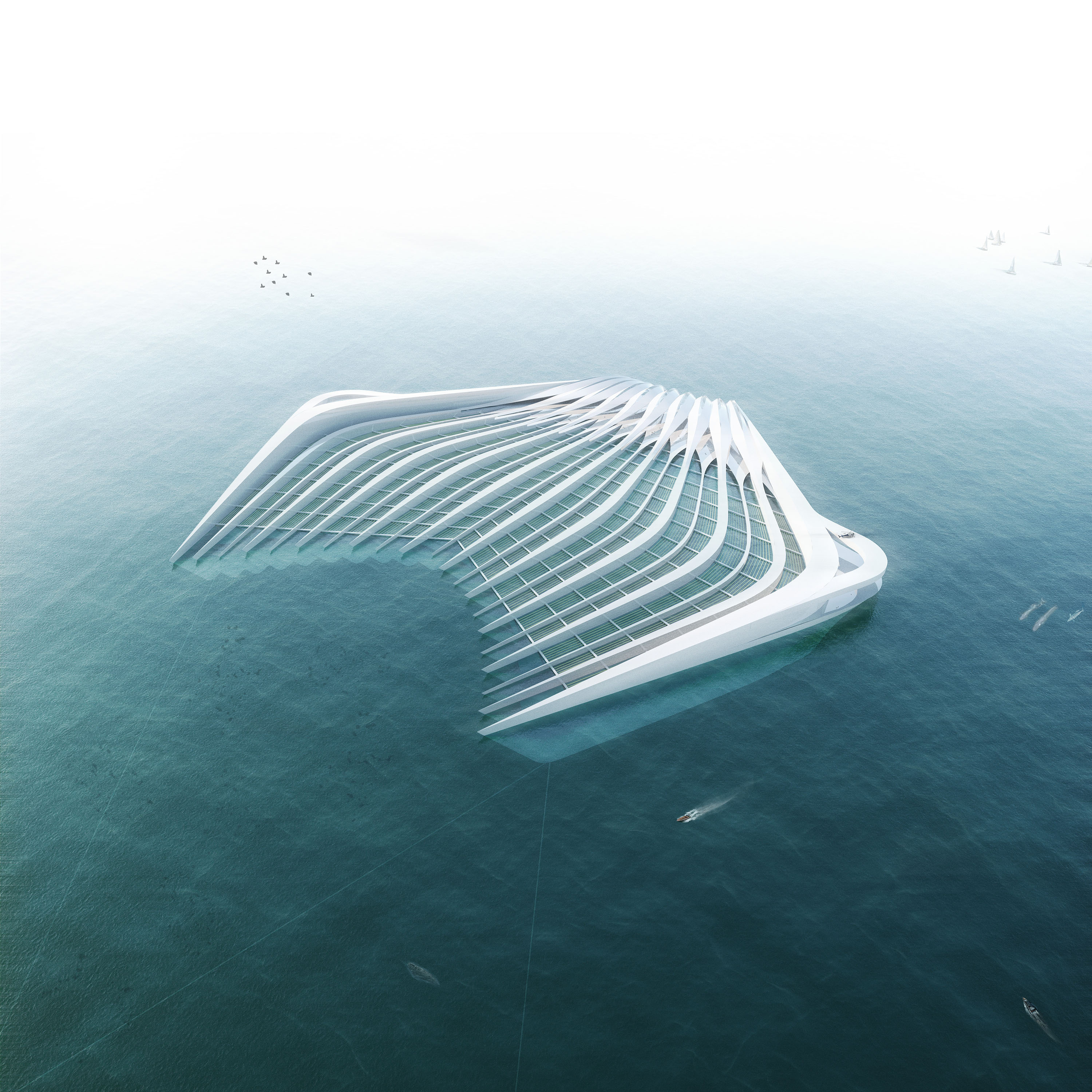

Her underwater encounter left a lasting impression. Oceanic researchers estimate that between 4.8 and 12.7 million tons of plastic waste wind up in the world’s oceans and seas each year. “If this continues, there will be more plastic in the ocean by 2050 than fish,” she said. For her project, the German set out to conceive a platform to filter plastic waste from the water. “I wanted to do something that would be really fun for me,” she said.

Thesis projects are generally not ever implemented. But Hansch’s project may have a future. A team is currently participating in an effort to bring it to life, after all, it would have been a shame for her idea to just disappear into a filing cabinet.

She becomes quite animated when explaining how her project started to take shape and how it became increasingly scientific, even though she said she is “more of an artistic person” and never really had much of a scientific bent. For this project, though, Hansch dared to go beyond the boundaries of her own field of study. She attended lectures on engineering, calculated ocean currents and learned about algae. The result was a system that functions as a closed loop and produces no waste at all.

Microbeads, also known as microplastic, are lighter than water so they tend to be found on or near the surface, though ocean currents can drag the bits of plastic as deep as 30 meters (100 feet) beneath the surface. Hansch’s calculations indicated that a bulbous shape and a system of underwater channels would calm the ocean currents, allowing the plastic particles to rise and be skimmed off the water surface by the platform.

Hansch speaks quickly and gesticulates with her hands as she explains her idea. She has presented her concept countless times – at her university, at conferences and in front of scientists. “The molecular structure of the plastic pieces that are filtered out of the water have been destroyed by salt water and cannot be reasonably recycled,” she explained. But Hansch still wanted to find a way to use the waste.

Her original plan called for the plastic waste to be run through a plasma gasification process to convert it to hydrogen and carbon dioxide. The hydrogen could then be used as an energy source for the fuel cells that power the platform. Meanwhile, the carbon dioxide could be used as a nutrient for the algae cultures grown on the platform. The algae biomass would then serve as the raw material for environmentally friendly, algae bioplastics.

While she kept the idea of a closed loop, not all of Hansch’s approaches proved to be realistic. The idea of plasma gasification has since been abandoned. Her team of researchers is currently investigating other possible solutions. “But even those should create hydrogen and carbon dioxide,” Hansch said, adding that the search for a practicable solution is ongoing.

“Does that make sense?,” Hansch asks after she finishes her explanation. It does – a conclusion by the many loved one who’ve supported her so far.

After graduating, Hansch began her career as an architect. During her lunch break one day, she visited the Institute of Hydraulic Engineering and Water Resources Management at RWTH Aachen University, where she presented her project. “I thought they would surely laugh at me,” she said. But nobody laughed. Instead, there was widespread interest in her work and ideas.

It was followed by invitations and the institute called on other students to do related thesis papers that could help Hansch advance the project. More people became involved.

For a long time, progress was painstakingly slow. At one point, Hansch even came close to throwing in the towel, but then she agreed to give one last presentation. It could have been the last speech she ever gave on the subject, but during the delivery, she had an epiphany and realized just how important it had become to her. “It became clear to me that I couldn’t just leave it behind,” she said.

A short time later, Hansch and her fellow campaigners started a non-profit organization called Pacific Garbage Screening. The NGO is composed of roughly 35 members, including engineers, environmental scientists and biologists. Together they are working towards the day when the platform can finally be deployed. They perform research on a voluntary basis and cover most of the costs out of their own pockets.

Although Hansch states it’s difficult to set a schedule for the project, she hopes that all the research underpinning it will be completed within the next five years.

Hansch said she is also taking pains personally to produce less waste. “I don’t run around lecturing people, but I do use humor to try to point a few things out.”

Photo credits: Marcella Hansch/Pacific Garbage Screenings.