When President Bashar al-Assad turns from the wreckage of Aleppo to assert his authority across a fractured Syria, it will be as a figure who is virtually unassailable by rebels, but still faces great challenges in restoring the power of his state.

The expected fall of Aleppo would mean rebels have almost no chance of ousting Assad, but their revolt has left him in hock to foreign allies, resigned to the loss of swathes of his country for the time being and with tough pockets of resistance still to crush.

"Certainly it is not the end of the war … But when you take Aleppo, you control 90 percent of the fertile areas of Syria, the regions that hold the cities and markets, the populated regions," said a senior pro-Damascus official in the region.

However, the battlefield victories that seem – for now – to have secured Assad's rule have been won in large part not by his own depleted military, but by Russian warplanes and a shock force of foreign Shi'ite militias backed by Iran.

Assad will rely on Moscow and Tehran to take back more territory, and to hold and secure it, meaning he will have to balance his own ambitions with theirs.

At the same time, as the insurgents lose ground and as the jihadists among them grow more dominant, conventional warfare may give way to an era of guerrilla attacks and suicide bombings within areas held by the government.

Aggravating this, the war has taken on sectarian dimensions that will resonate for generations; the uprising identifies itself with the Sunni Muslim majority, and the state led by a minority Alawite draws on the backing of Shi'ite Islamists.

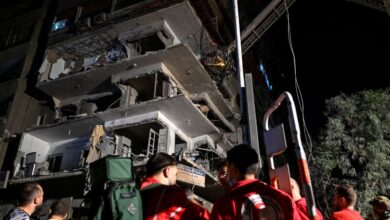

Worst of all, nearly six years of war have killed hundreds of thousands of Syrians, displaced around 11 million, of whom nearly half have fled the country, and laid waste to much of the infrastructure needed to resurrect a shattered economy.

In rebuilding, Assad will also have to contend with Western sanctions on much of his government and with isolation from some of his main previous trading partners – the European Union, Turkey, Gulf monarchies and Jordan. The Gulf states in particular may also continue to fund insurgents.

"Syria has suffered such wounds that there will always be, in my expectation, a day of reckoning," said Nikolaos Van Dam, a former Dutch diplomat and author of a book about Syrian history and politics, speaking about the future of Assad's state.

INDISPENSABLE

To his supporters, Assad is the one, indispensable figure standing between his country and absolute chaos, the resolute leader of a war against foreign-backed jihadists who wish to slaughter minorities and launch attacks on other states.

Without him, they say, what remains of the Syrian armed forces and security services will crumble, rendering the country a failed state and a danger to the world for decades to come.

Convincing enough allies – including Moscow and Tehran – to see him in that light has been Assad's "political masterpiece", said Rolf Holmboe, research fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute and a former Danish ambassador to Syria.

But to his detractors, Assad is the man who burned Syria rather than allowing power to slip from his grasp, a dictator whose prisons are wallowing in the blood of his opponents and whose cities lie ruined by the bombs of his military.

In Assad's swift use of force against protesters in 2011 and his deployment of artillery and air power against Syrian towns and cities, critics see his reliance on the example of his father, Hafez al-Assad, who ruled from 1970-2000.

Hafez's crushing of an Islamist insurgency that began in 1976, culminating with the massacre of thousands in the city of Hama in 1982, set the template for his son's response to the Arab Spring protests in 2011 and the subsequent war.

"They have no other solutions and that's it. They implemented the same manual. They took it from the drawer and implemented it," said Ayman Abdel Nour, a former friend and pro-reform political appointee of Assad who left Syria in 2007.

For Abdel Nour, Assad at war was a far cry from the man he first knew at Damascus University in the early 1980s, long before the death of an elder brother put him in line to succeed his father as president.

"He was like any other person: very humble, very nice, very modest because he was not supposed to be president," he said.

Assad's early years as president after succeeding his father in 2000 raised hopes of political and economic reforms, but they mostly faltered, something that was blamed at the time on an old guard of security chiefs.

RAQQA WRITTEN OFF FOR NOW

The president and his allies have focused their campaign on the populous, fertile, west of his country and few people expect him to lavish limited military resources on quickly retaking the eastern deserts or Euphrates valley area from Islamic State.

The senior pro-Damascus official said that Assad had for now written off Raqqa, which has become the de facto Syrian capital of Islamic State, often referred to by the Arabic term Daesh, regarding the jihadist group as Washington's problem to fix.

"The regime forgot about Raqqa a long time ago and made it the responsibility of the Americans. Let those alarmed by Daesh go and remove it," the official said.

Still, Assad himself signaled in a December television interview that in the end he intended to restore Damascus' sway across the country. Asked about a "federalist" system that Kurds have implemented in parts of north Syria from which the central state has retreated, he dismissed their local councils as "temporary structures".

In making further military gains after Aleppo, Assad will continue to rely on both Moscow's air power and the ground force supplied by Iran and the Shi'ite militias it sponsors, foremost among them the Lebanese group Hezbollah.

Several thousand foreign militiamen have already died fighting for Assad, often in the fiercest fronts of the war, and Assad's regional enemies believe that will make him little more than a vassal for stronger allies who have their own agendas.

Abdulaziz al-Sager, Saudi head of the Jeddah-based Gulf Research Centre and the man asked by Riyadh to mediate talks between Syrian opposition groups last year, believes this has left Assad too weak to rule effectively in the long term.

"My opinion from day one is that Bashar al-Assad is in a losing battle. Even if he gains some position, who is really today ruling Syria? It's the Russians and the Iranians. He has very little role to play there," he said by phone.

Assad himself said in the television interview that he consulted with Russia daily, adding that "no decision is issued without discussions between the two countries".

In Moscow, Vladimir Dzhabarov, a retired Russian special services general and a deputy chairman of the international affairs committee of Russia's upper house of parliament, said his country had no ulterior motives in Syria. "Our leadership has always been saying that we don't support Assad but the rule of law in this country," he said.

Still, Assad is not without power in his dealings with his allies; both Moscow and Tehran are relying on his presence to keep the government and security forces intact and justify their massive outlay on the war, given few people believe there is a plausible alternative to him among the senior ranks of his administration or military.

"Iran and Russia and Hezbollah, they also need him. Russia and Iran are quite limited in their possibilities of influencing him," said Van Dam.

SECULARISM

One consequence of the fall of Aleppo could be that nationalist rebel groups – the ones that Western countries feel able to support – will be weakened while militant jihadist ones come to dominate the insurgency even more.

"Assad is one step closer to his aim of making sure the rebel landscape is more terrorist, in his language, which in his strategic view will be a way to reach out to the West to fight terrorists together," said Holmboe, the former ambassador.

In making that argument, Assad has always emphasized the secular nature of his ruling Baath party, a socialist, pan-Arab movement embraced by his father, who seized power in a coup and first built Syria's alliances with Moscow and Tehran.

But critics say that while Assad has contrasted the secular nature of his party's ideology with the Islamist beliefs shared by his own domestic opponents and militants who threaten other countries, his actual policies have been highly sectarian.

The Assads are members of the Alawite sect, a minority Shi'ite offshoot that hardline Sunni Islamists regard as heretical and whose members have been given many of the top posts in the bureaucracy, military and internal security forces.

"In a certain way, still the regime is secular but the composition is not secular," said Van Dam, who added that any hopes for future reconciliation between Syria's sects would be hard to achieve "for many, many, many years".

Some of his foes used to hope for an internal coup that might allow a more compromising figure to emerge but as his government secures more victories, it is hard to see why or how other figures within the state would remove him.

"He always put rumors against each one of them. Everybody hates each other. Every officer of the intelligence, his deputy is totally against him. So that's it. No one can move. No one can do anything," said Abdel Nour.