ROJ CAMP, Syria (AP) — It was night when Zakia Kachar heard the sounds of footsteps approach her tent in a detention camp for foreigners affiliated with Islamic State group extremists. With rocks in their hands, the wives of IS fighters had come for her.

She fled with her children to another area of the Roj Camp in northeast Syria. “They wanted to kill me,” she said.

Earlier that day, the dual Serbian-German national had fought back in an altercation with a camp resident disapproving of her wearing makeup. The woman had bitten her, and Kachar slapped her in defense.

Such clashes between hard-line IS supporters and those who have fallen away from the group’s extreme ideology are exacerbating security challenges for the U.S.-backed, Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, or SDF, which runs Roj and other camps for IS detainees.

The SDF had spearheaded the fight against IS, driving the militants from their last sliver of territory in 2019. Three years later, tens of thousands of foreign IS supporters remain in SDF-run camps and detention centers, with their home countries largely unwilling to repatriate them. The foreigners had come to Syria from around the world, some with their children in tow, to join Islamic State’s so-called “caliphate.”

The SDF now points to the lockups—crammed with restless detainees, some with a history of violence— as a chief source of instability across the region they control.

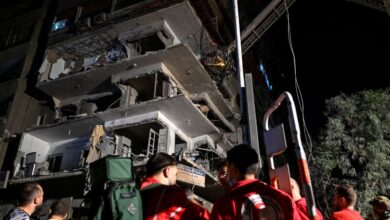

A deadly prison attack in the Gweiran neighborhood in the town of Hassakeh last month sharpened the focus on the foreigners’ uncertain futures and the limits of their Kurdish captors to supervise them. The assault killed 121 security personnel and took authorities nearly two weeks to contain.

Stretched thin amid an economic crisis and rising threats from IS sleeper cells, the Kurdish-led administration is renewing calls for countries to repatriate their citizens.

“We are struggling,” said Mazloum Abdi, the region’s top security chief and commander of the SDF.

NO WAY OUT

In Roj camp, home to some 2,500 women and children, a tune popular among youth in North America resonates.

For a few minutes, the melody cuts through the din of daily life, overpowering the sounds of U.N.-emblazoned tents flapping in the wind and children playing.

The music—a soulful song called “Later” by Somali-Canadian singer A’maal Nuux—came from the tent of Hoda Muthana, an Alabama native whose Supreme Court appeal to return to the U.S. with her 4-year-old child was denied last month. The lyrics describe the sisterhood of women on a long commute to visit their partners serving time in prison.

Her neighbor is Shamima Begum, a British-born woman stripped of her U.K. citizenship in a case that drew international attention and raised questions about the moral responsibilities of countries toward IS members.

Their days are marked by monotony. Mothers cook, clean and wait for word on their repatriation appeals.

Several women in the camp in Hassakeh province removed the black garb of IS wives, instead wearing jeans, baseball caps and makeup forbidden during IS’s brutal rule. They are kept separate from their hardline neighbors who frequently attack them.

Tents, made of flammable cotton canvas, have been burned down to sow chaos.

Neither Serbia nor Germany has given Kachar any indication they would be willing to repatriate her or her five children, ages six to 16.

Kurdish authorities said up to 200 security personnel have been added to maintain Roj Camp since the Gweiran prison attack.

“Our security forces are present, but the problem is the ideology of some of the women,” said one official in Roj, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to brief the press.

Kachar’s daughter was only 11 when they followed her husband to Syria from Stuttgart, Germany in 2015. “I want to go home, it is enough. My children need a normal life,” she said.

‘A SHARED RESPONSIBILITY’

It is al-Hol Camp, many times larger than Roj with 56,000 refugees and displaced people, where security is the most dire and humanitarian needs most acute.

There is no law and order and women there have been killed just for removing their niqab, the veil worn by conservative Muslim women, security officials said.

Most, though not all, non-Arab foreigners are housed in an annex of al-Hol. The United Nations says there are 8,213, of whom two-thirds are minors. Another 30,000 are Iraqi nationals.

Kurdish security officials and non-governmental organizations present in the camp said security began deteriorating in March 2021 with targeted killings of camp community leaders.

Many reported increased cases of extortion, blackmail and death threats toward security and NGO workers.

Kurdish authorities say the camp is a breeding ground for IS, with active sleeper cells. Aid workers attributed the growing criminal activity to desperation arising from widespread poverty, stigma and limited freedom of movement.

Recent violence spurred by the smuggling of weapons and other illicit activity has also raised questions over the complicity of SDF authorities. Abdi, the SDF commander, acknowledged there were some incidents of corruption.

“Some trucks for example, are supposed to be water trucks but they are smuggling out human beings. And of course, if they can take out humans, they can bring in weapons,” he said.

The SDF has been in talks with international NGOs over new security arrangements for al-Hol that would divide the camp into sections, limit movement between areas, and erect fences, checkpoints and watchtowers. Many aid workers fear this would turn the camp into a de facto prison for women and children.

To decrease the pressure on al-Hol, at least 300 families were recently transferred to Roj Camp. Another 150 families are expected this year.

“It has caused us more issues because these women are encouraging others to be radical like them,” the Roj camp official said.

Some countries are taking their nationals back, gradually. The Netherlands and Sweden recently repatriated several women.

Abrar Muhammed, 36, a detainee and former IS logistics manager, believes his wife may have been among them. The Swedish citizen was informed in passing by a prison guard, he said.

Muhammed hasn’t seen his wife since January 2019, when he fled the IS ranks and was detained at an SDF checkpoint, months before the fall of the group’s last territorial foothold, the village of Baghouz in northeastern Syria. He has been jailed in one of the 27 detention centers across northeast Syria ever since.

“I want to go back, face justice in Sweden,” Muhammed told The Associated Press in a facility in Hassakeh. “In a country with laws.”

Abdi said the international community has to take some responsibility for the prisons and camps.

“It’s not just our problem, we share the burden. This is our demand.”