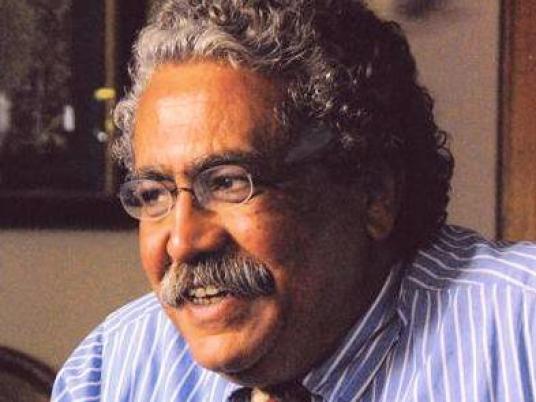

On Sunday, former editor-in-chief of Ahram Online Hani Shukrallah, bid his final farewell to the organization, after a series of measures by the Brotherhood-administered media institution that chipped away at his authority along with his salary, arguably aimed at silencing English-speaking media.

“The deed is done: the MB has now fulfilled its resolve to drive me out of Ahram,” Shukrallah posted on his Facebook page, explaining that he hung on after decisions to cut his salary in half, force him into early retirement and cut the remaining half of his salary by two-thirds.

“Just today I found out that in a meeting with a committee formed by Ahram Online staff to negotiate with the management, they were told that my status was ‘too complicated,’ and that (despite previous denials that it'd all been a bureaucratic mistake) the third of one half would remain in place, while my connection with Ahram Online would depend on the wishes of the new editor (who's yet to be named),” Shukrallah wrote.

Ahram Onlne, an English-language news portal launched in 2010, is part of the state-owned Ahram Institution.

He explained he was leaving the institution with “zero savings,” and would have to sell his car to pay back Ahram what he owes.

“But fools! I have something immeasurably more precious: my dignity and self-respect. What do you have?”

Local English-language media continues to face political and economic blows as it struggles to survive in an Arabic-speaking country.

Nonetheless, although grossly outnumbered by Arabic counterparts, local English-language media can sometimes have more influence in terms of readership and the topics tackled. While expats constitute a large portion of their audience, these outlets act as a vital resource for diplomats, policymakers and think tanks, both in Egypt and abroad.

Almost 50 percent of the traffic on English news websites comes from outside of Egypt. For Abdel-Rahman Hussein, who has worked as a reporter for Daily News Egypt, Egypt Independent and as a foreign correspondent for The Guardian, Egypt’s local English-speaking media is the most vital source of news.

“It manages to avoid the pitfalls of both the Arabic and foreign press, while offering a depth rarely afforded in the other two,” he explains. With a few exceptions, he finds local English-language media to be “the complete package,” offering in-depth news with a nuanced understanding of the political, social and cultural contexts.

“It also tends to portray the most accurate narrative of events on the ground, not the pastiche-laden narrative ubiquitous in the Arabic press, nor the nonchalant narrative processed through a different prism that is sometimes found in the international media,” he adds.

But despite its local and global importance, independent English news outlets in Egypt face numerous obstacles, in particular, the lack of a sustainable business model.

Economic and political hardships

In 1996, prominent publisher Hisham Kassem launched the now-defunct independent English-language magazine Cairo Times. He recalls a conversation with a major advertiser who told him that a full-page ad in the Cairo Times, which only printed 5,000 copies, had more reach than one in the state-owned daily Al-Ahram.

Rania Al Malky, former editor-in-chief of Daily News Egypt, says Cairo Times was a “unique experiment” that boldly tackled taboo topics. “It came out during a time when it was impossible to say what they were saying and impossible to speak to the people they were speaking to,” she says.

English-speaking local media were the first to cover human rights violations under former President Hosni Mubarak. These outlets were also credited for highlighting labor movements and workers’ rights, topics long absent in other mediums.

Kassem recognizes the need for local English media to thrive, but says it depends on feasibility. “There is state-owned media and there’s the private sector,” Kassem says. “The private sector is dependent on the economy, which is why Daily News Egypt closed down.”

In April, seven years after its conception, the Daily News Egypt staff were abruptly informed that the paper would no longer be printing for economic reasons. After the staff was let go, the brand was later sold to a local investor, and it started printing again.

Economic hardships were also the reason behind Cairo Time’s demise, but with a political twist. The magazine never shied away from criticizing Mubarak’s regime, but ultimately lost its showdown with the censors.

“It came to a point where I was verbally banned to print in Egypt,” Kassem says. He would fly to Cyprus and return with the copies as cargo. “We would print and they would confiscate,” he says.

This tug of war continued until the powers-that-be shifted their attention to advertisers, and, Kassem says, starting threatening them. This took a toll on revenue, and after seven years of printing, Cairo Times announced its bankruptcy.

Nonetheless, Kassem is confident that these repressive practices will not be repeated with post-25 January media. “Even with all the Muslim Brotherhood’s absurdity,” he says, “if they tried to tighten their grip on the media, they won’t succeed.”

Kassem says the Brotherhood was able to force Shukrallah out of Ahram Online because it is still considered state-owned media. “But what can they do with publications like Egypt Independent, for instance?” he asks.

While even state-owned English-language media enjoy a greater degree of freedom of expression than their Arabic counterparts, they’re still vulnerable to some restrictions, says Rasha Sadek, reporter at Al-Ahram Weekly.

Under Mubarak, this was true “especially when it came to … incidents of torture practiced by the interior ministry, and other human rights violations,” Sadek says.

She cites an incident where an award-winning report uncovering torture inside prisons cost the editor-in-chief his job at a newspaper she preferred to leave unnamed. A National Democratic Party member subsequently replaced the editor, she says, and this was how the regime maintained its grip on media.

After the revolution, Sadek says, English local media managed to remove more red lines, but “how long it can maintain this margin of freedom is anyone’s guess.”

That is not to say that President Mohamed Morsy and the Brotherhood are not concerned about their image abroad, even more so than Mubarak. Unlike Mubarak, however, the Brotherhood does not understand the dimensions of the international scene, Kassem says.

“I’ve been through it all … and I can say that things are opening up,” he continues, explaining that with social media and blogging, “even technology alone has defeated censorship.”

Local vs. foreign media

Local publications’ survival also depends on whether they can face the competition. “Local English-speaking media is like a luxury item no one wants to invest in,” Malky says, explaining it faces fierce competition from international media, whose level of interest and coverage of Egypt has skyrocketed since the revolution.

While Malky acknowledges the necessity of offering expats, diplomats and policymakers this kind of content, she says it is increasingly becoming available on several platforms, chipping away at local media’s niche market.

“We want to give readers a nuanced news perspective from a local point of view in English — this need hasn’t changed, but there’s a lot more competition,” she says.

Kassem considers local independent English news outlets a better resource for readers who seek to understand Egypt than The New York Times, for instance. “Local journalists know the country inside and out. They have more credit,” he says.

For David Kenner, associate editor at Foreign Policy, it is also an issue of trust. He explains that problems faced by foreign and local media are different, adding that foreign reporters often face the problem of “access.”

“It can be difficult to reach certain groups or parts of the country that an Egyptian journalist might be able to contact easily. This is partially due to trust — a foreign reporter, of course, is always vulnerable to being the target of smears that they’re a spy.”

Nonetheless, he admits that it also comes down to “knowledge.”

“A foreign journalist’s stint in Egypt is limited, and they won’t have the social and professional network that a local journalist would, by virtue of having spent his or her life in the country.”

For Sadek, local English media has an edge because it is “locally made.” It requires, she says, “a certain degree of understanding of the mechanisms and dynamics of Egyptian society and culture to be able to accurately report on certain events. Without this, foreign reports can often be misleading,” she says.

Kenner says that local reporters, on the other hand, are more vulnerable politically. “They’re not distant observers of Egypt’s political scene, but engaged every day in the drama of their country’s political life,” he says.

And although English-speaking local media is becoming difficult to sustain, Kassem says it still maintains a higher professional level than Arabic media.

Malky also sees this discrepancy, pinpointing a difference in the newsrooms culture. “Arabic press has become more partisan, as opposed to its English counterpart, which is more professional in covering stories,” she says.

Hussein also believes English-language media is less prone to hyperbole and more likely to be accurate. But for it to survive, Malky says, it needs to create an edge by focusing on investigative journalism, which is not prevalent in Arabic media.

This piece appears in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.