Dozens of environmental activists and desert lovers peacefully demonstrated in Wadi al-Rayan last Friday to show their disapproval of a wall they say spoils one of the country’s most beautiful natural reserves.

The valley has been threatened since a group of monks started building churches and monasteries on its land, surrounding them with a 10-kilometer-long concrete wall.

A unique protected area in Fayoum Governorate, Wadi al-Rayan attracts nearly 190,000 tourists each year. Because of its biological, geological and cultural resources, the government designated it a protected area in 1989. UNESCO declared it a World Heritage site in 2006.

In 1996, three monks resorted to the area’s mountain caves to worship. They reached an agreement with the Wadi al-Rayan administrators to live in some of the caves.

This agreement stipulated that the monks could live in the caves as long as they did not harm the area or use land to build on.

“We used to visit those caves and sit with the three monks as a beautiful part of our trip in the valley,” says Gary Garbis, one of the main protest organizers. “A few months before the revolution, the number of those monks increased in a strange way. They started some building and cultivating activities that partly destroyed the place. Therefore, the administrators of the reserve refused to renew the old agreement.”

Garbis says the monks rapidly started to build churches and monasteries, expanding more and more on the reserve’s land. In addition to cultivating crops such as wheat, sucking up the area’s limited groundwater, they started breeding rabbits and hens.

When the revolution began, they seemed to take advantage of the police absence, and started building the wall to prevent anyone from breaking into the monastery. In front of the wall, they put a sign that carries the name, “The Monastery of Alexandrian St. Macarius in Wadi al-Rayan.”

Khaled Sobhy, an environmental activist and another main protest organizer, says the illegal wall extends between the eastern and western Manakeer Mountains, surrounding a space that exceeds 30 square kilometers, or 9,000 acres.

The activists say that in addition to the wall’s unattractive appearance, it seriously threatens the local ecosystem. There are four water springs called “magic springs” because they are considered the only water source for all the wild animals that live in Wadi al-Rayan, Sobhy explains.

“The valley contains some rare endangered species that exist only in Egypt, such as the white and Egyptian gazelle, and red and sand fox, in addition to some unique species of rabbits,” he says. “This wall prevents the animals from reaching water sources, which will lead to their death and extinction.”

Sobhy says the Fayoum governor decided to demolish the wall and the other legal constructions on the protected area land on 1 October last year. Nine months ago, the Armed Forces came to demolish it and took down a small part, but couldn’t finish it because the monks confronted them.

The monks then started rebuilding the wall and expanding it, he says. He adds that civil engineers have estimated the cost of building the wall at more than LE8 million, and wondered where the monks would get that kind of money.

“Who will benefit from the destruction of this natural reserve? Why wasn’t the governor’s decision implemented until now?” Sobhy asks.

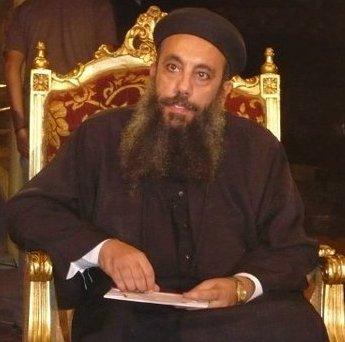

One of the monks, Pachomius, was commissioned by the monastery to confront the demonstrators.

“By building these churches and monasteries, we aim at protecting our Coptic Christian heritage,” he says. “The old manuscripts show that our Coptic ancestors had an old monastery here in the 14th century.”

He says that the monks work in cooperation with the Environment Ministry to welcome tourists who visit the valley, and that the building of the monastery was supervised by the Coptic Orthodox Church.

In a previous interview with Egypt Independent, Father Eisha, one of the monks at the monastery, had said the wall was a necessary security measure. Since the revolution, he said, Bedouins threatened many of the monks, and police were unable to defend them.

“That is why we had to build this wall, to protect ourselves,” he said.

But Arafa al-Sayed, administrator of the protected area, says these claims aren’t true.

“There had never been any monasteries on the reserve land, and they didn’t get permission from the Environment Ministry,” he asserts. “On the contrary, the reserve administration submitted many complaints against those monks in the past years, and some of them were sentenced to imprisonment.”

The constitution dictates that no one is allowed to cultivate, build or pave roads in natural reserves. The valley the monks occupy, Arafa says, is one of the most sensitive and fragile areas in the reserve.

Bassem al-Bayady, a Coptic environmental activist, says he visited the Coptic Orthodox Church to find out if the monks had been given permission to take over the protected area and build religious buildings on part of it.

“The church described them as ‘dissident monks,’ declaring that they don’t belong to the [church], which has no responsibility for their actions,” Bayady says.

Sophie Allahony, who owns a tourist cafeteria in Wadi al-Rayan, says the wall construction enormously affected tourist projects in the area.

“We used to take the tourists on tours on camels and horses to show them the water springs and the rare animals,” Allahony says. “Now, the wall surrounds the springs, and the monks don’t allow anyone to enter the place.

Many animals have died, Allahony adds, saying this has influenced eco-tourism in the area and made it lose its value.

Sobhy says he doesn’t want this problem to cause sectarian problems.

“People must know that it has nothing to do with religion. Half of the demonstrators are Christians,” he says. “This case can open the door for anyone to steal our natural reserves. Thus, we have to stand hand-in-hand to prevent this individual case from turning into a phenomenon.”

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent’s weekly print edition.