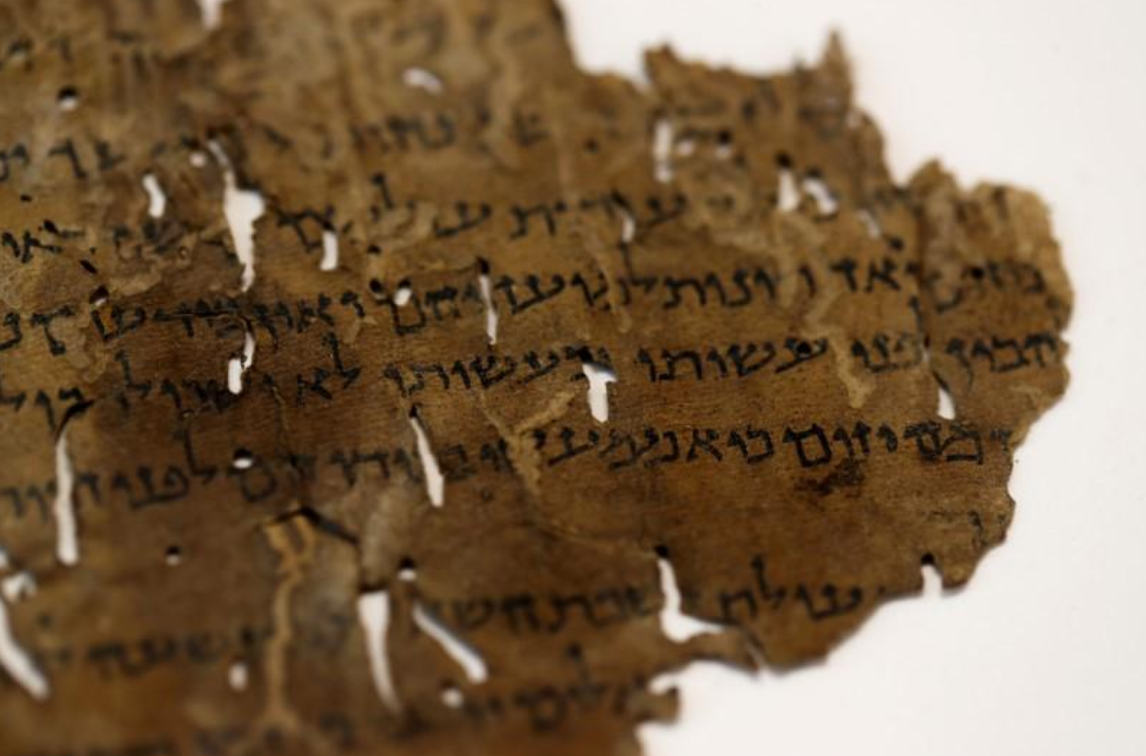

JERUSALEM (Reuters) — Genetic sampling of the Dead Sea Scrolls has tested understandings that the 2,000-year-old artifacts were the work of a fringe Jewish sect, and shed light on the drafting of scripture around the time of Christianity’s birth.

The research — which indicated some of the parchments’ provenances by identifying animal hides used — may also help safeguard against forgeries of the prized biblical relics.

The Dead Sea Scrolls, a collection of hundreds of manuscripts and thousands of fragments of ancient Jewish religious texts, were discovered in 1947 by local Bedouin in the cave-riddled desert crags of Qumran, some 20 km (12 miles) east of Jerusalem.

Many scholars believed the scrolls originated with the reclusive Essenes, who had broken away from the Jewish mainstream. But some academics argue the Qumran trove had various authors and may have been brought from Jerusalem for safekeeping.

DNA sequencing conducted by Tel Aviv University and the Israel Antiquities Authority has allowed for finer matching or differentiation among the scrolls.

While the sheepskin of some of the scrolls could be produced in the desert, cowskin — found in at least two samples — was more typical of cities like Jerusalem, where Jews, at the time, had their second temple and were under Roman rule.

“The very material, the biological material of which the scrolls are made, is as telling and as informative as the content of the text,” Noam Mizrahi, Bible studies professor at Tel Aviv University, told Reuters.

The Israeli researchers, assisted by a Swedish DNA lab, determined that two textually different copies of the Book of Jeremiah were brought to Qumran from the outside.

Such findings, the researchers say, indicate that the wording of Jewish texts was subject to variation and interpretation — contrary to later views of holy writ as fixed.

The lesson, Mizrahi said, is that “Second Temple Jewish society was much more plural and multifaceted than many of us tend to think”.

Tiny slivers of parchment — or just dust — were taken for testing. The process could prove a godsend for spotting counterfeits, such as five supposed Dead Sea Scrolls that were removed from the Museum of the Bible in Washington in 2018.

“Since we can distinguish scrolls that originated from Qumran from other scrolls, we think that maybe in the future it could help identify real versus false scroll pieces,” said Oded Rechavi, neurobiology professor at Tel Aviv University.

___

By Dan Williams, Rinat Harash

Writing by Dan Williams; editing by Philippa Fletcher

Image: A fragment of the Dead Sea Scrolls that underwent genetic sampling June 2, 2020. (REUTERS/ Ronen Zvulun)