Until the 1970s indoor air quality in the non-industrial sector – in homes and work environments, for example – was neither particularly studied nor a subject of concern. What gave rise to awareness was the outbreak of diseases caused by exposure to asbestos, a group of minerals with insulation capacities and a resistance to heat and chemicals that made it extremely useful for the construction industry.

Unfortunately, little has still been said about common indoor air quality, which can be extremely low quality and detrimental to human health, causing a wide range of illnesses including pneumonia, respiratory problems, allergies and infections.

“Indoor pollution mainly comes from outdoor pollution,” explains Hameed Awad, head of the air pollution department of the National Research Institute (NCR) in Dokki. A lot of particles enter homes and offices through air conditioning devices, or even through doors, agglomerated under the soles of shoes. Air conditioning not only enables these particles to enter buildings, but ventilation systems help them disseminate around a house.

The majority of building-related illnesses are thought to be caused by bioaerosols, which are airborne particles of microbial matter which can be inhaled deep into the lung. Bioaerosols are bacteria, fungi, enzymes, hair – indeed all kinds of living organisms suspended in the air small enough in size that they are easy to inhale and get embedded in the lungs. They contain a mixture of particles from different origins (plants, animal and microbes) and constitute the most common indoor air pollutant worldwide.

Having pets inside a household therefore increases the presence and the growth of fungi and fungal spores.

“If the surroundings of the building are covered in piles of trash, and have no paved roads, the amount of outdoor pollution that will make its way indoors is obviously much higher than in a cleaner environment,” Awad explains, adding that in Egypt, “there is a particularly high count of micro-organisms indoors compared to other countries because the local temperature is very suitable for them to reproduce.” Micro-organisms need two optimum conditions to thrive: moisture and high temperature.

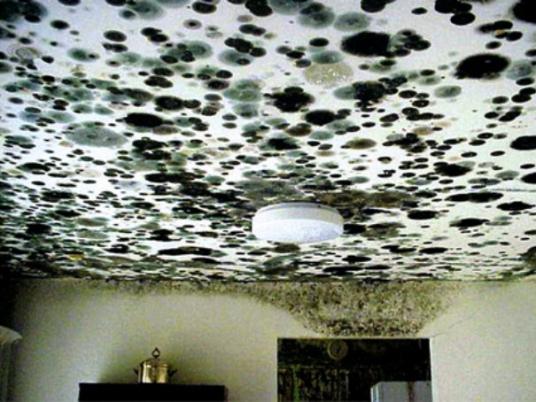

Additionally, many buildings in Egypt are not maintained properly, to the detriment of indoor air quality. Leakages are frequent, prompting the speedy reproduction of microbes and molds, and when steps are not washed regularly, dust and particles are brought into houses and offices.

“Sick building syndrome” describes a situation in which reported symptoms among a population of building occupants can be associated with their presence in that building. The most prevalent building-related illnesses are hypersensitivities, which include hypersensitivity pneumonitis, humidifier fever, building-related asthma, allergic rhinitis and infections. Headache, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, irritation and dryness of the mucous membranes, and skin problems are all symptoms which fade away when the person leaves the corrupt air quality of the “sick building.”

Building-related health issues pose many challenges to health professionals as it is a difficult task discovering the specific agent that caused a patient’s illness. “Doctors have a hard time relating a patient’s condition to indoor air quality specifically, because his condition is symptomatic of general exposure to environmental factors,” Awad explains, adding that the other challenge confronting indoor air quality studies is the lack of governmental standards to specify the acceptable concentration of indoor airborne fungi and bacteria.

Also, each individual will react differently according to his immune system, and while one will develop an acute allergy crisis, runny nose and irritated eyes, another will not respond physically to the presence of micro-organisms and bioaerosols.

The Stachybotrys, a common filamentous fungi also known as “black mold” appears after fungal growth on water-damaged building materials and forms dark circles on ceilings and walls. Depending on the length of the exposure to this fungi and the amount of spores inhaled or ingested, symptoms can manifest as chronic fatigue or headaches; fever; irritation to the eyes, mucous membranes of the mouth, nose and throat; sneezing; rashes; and chronic coughing. In severe cases of exposure or cases exacerbated by allergic reaction, symptoms can be extreme, including nausea, vomiting, and bleeding in the lungs and nose. “This fungi, which develops in humid cracks indoors, can also trigger bleeding in infants,” explains Awad.

There are basic solutions to limit the pollution inside a living environment, and this goes hand in hand with a change of habits, according to Awad. “Some people have wrong reflexes, they clean carpets indoors and enable all the particles to be released in the air and easily inhaled,” he says, adding that houses need to be more ventilated and better kept, hygiene-wise.