BARCELONA — The appointment was at 11 am last Friday in downtown Barcelona. The protest had been organized in secret, so nobody else — and certainly not the Catalan police force — was expecting it.

Everybody arrived on time, for they were going to perform a new “prank,” this time, perhaps a little wilder than before. A hundred members of the Iaioflautas collective, composed of older activists, “occupied” the city’s stock exchange.

Wearing their yellow waistcoats and armed with banners and whistles, their chants echoed among the employees and computer terminals: “Hands up, this is a holdup!”

“We came here today because the stock market is a symbol of the economy. We are not going to pay the debt. We are for bailing the people out, not the banks,” says 62-year-old Celestino Sanchez.

Last night, 25 September, police in Barcelona used truncheons to disperse a crowd of thousands who had formed a human chain around the Congress building. It wasn't an isolated protest, however, but a moment in a movement which traces its lineage back to the massive protests that took place across Spain in spring of last year. Egypt Independent spoke to participants about the movement.

Sanchez is one of the youngest and best-known members of the Iaioflautas collective, which emerged in Barcelona a year ago alongside the encampment in Catalunya Square. They call themselves “the children” of the Indignados (the outraged) movement, despite the fact that the majority of them far exceed the age of 60. They are retired, they are “iaios” — grandparents, in Catalan — and they are veterans of long-term activism.

The rebel grandparents are one of the many diverse groups active under the Indignados umbrella, which was itself created on the Internet by a citizen-based, digital platform, Democracia Real Ya (Real Democracy Now), in February 2011. Indignados launched its first street protest across Spain and some European cities on 15 May.

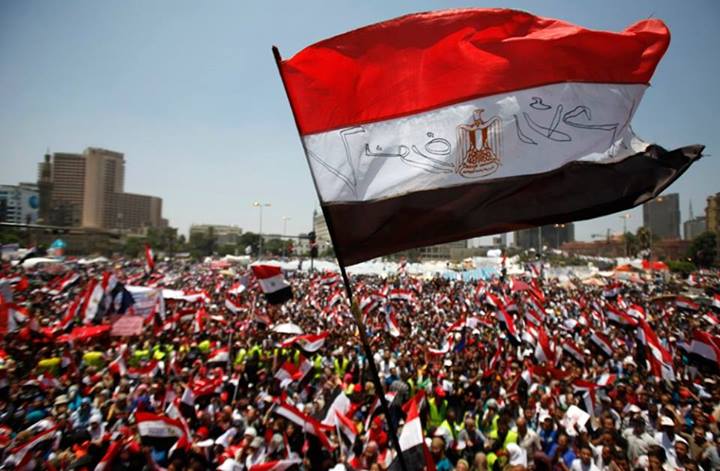

The 15-M, as the movement is called in Spain, grew out of social discomfort with the management of the economic and financial crises, and was inspired by the revolts in both Iceland and the Arab world. It drew from the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions the use of digital tools for organizing and the occupation of key public spaces. An area of Barcelona’s Catalunya Square camp was named “Tahrir.”

The 15-M launched two clear messages, able to unite a broad spectrum of citizens: “We are not goods in the hands of politicians and bankers,” and “They call it democracy but it is not.”

Sixteen months later, the list of political and economic reasons that took the Indignados to the streets is even longer, and the bases for social explosion are there. Youth unemployment is more than 50 percent, the highest in the European Union. University fees have doubled, and Bankia, one of Spain’s biggest banks, is about to receive a multibillion bailout from the public purse while austerity measures have pushed the country back into recession.

The 15-M movement is not just about defending the health and education systems or resisting bank bailouts and mortgage foreclosures. Its members are also asking for a better, more participatory and direct democracy. Other reasons for outrage include political corruption, the privileges of political parties and the fact that citizen participation in public affairs is almost completely limited to voting every four years.

Since it began, the movement has evolved through different stages. Joan Subirats, political science professor and researcher at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, says one of the key moments was when the movement realized that “maintaining the occupation of the squares was going to be difficult and withdrew into the neighborhoods.”

The movement went local, and since then hundreds of small groups and assemblies in villages and neighborhoods — with a myriad of blogs, Facebook pages and Twitter feeds — have kept the flame alive. These groups have taken up many causes, from welfare cuts and the fight against immigrant detention centers to stopping forced evictions.

A poll in El Pais newspaper in May showed that 51 percent of Spaniards sympathized with the movement, although this had fallen from 64 percent a year ago.

“The movement has the capability to remain active. Every time it was pronounced dead, it reappeared,” Subirats says.

The impact of the 15-M movement on traditional politics is not negligible. It has generated a new atmosphere and a process of re-politicization, which have delighted the Iaioflautas, who were dreaming of going out into the streets to fight again for the rights they had fought for before.

“It has generated a momentum for change and shown that politics can go beyond political parties,” Subirats says.

One example of this is the Platform for Those Affected by a Mortgage, which was created in Catalonia in 2009 to try to find a solution to the drama of forced evictions. It has become stronger and more effective in the past year. Another 15-M-affiliated network is taking Bankia to court.

Just like the anti-eviction groups, Iaioflautas groups have spread to other parts of Spain.

“When I get older, I would like to be an Iaioflauta” was trending in the Spanish Twitter sphere as they occupied Barcelona’s stock exchange.

Sanchez says that the 15-M movement is now in the process of recentralizing and beginning a “constitutional process.” It began Tuesday, 25 September, under the Twitter hashtag #25S, with the Surround the Congress, or Rodea el Congreso, initiative in Madrid.

The manifesto of the organizing group demands the dismissal of the entire government and the beginning of a process to write a new constitution to replace the one from 1978, which was agreed upon during the transition from Franco’s dictatorship.

“The Spanish Constitution was not voted for by the last generations. It is not respected, and last year it was amended all of a sudden,” says one protest organizer from Madrid.

The Spanish Constitution has been reformed only twice, with the second time being a year ago, an effort to limit the deficit.

“We are asking for a participatory people’s constitutional process. It will be a long-term process, but it is clear that people have said ‘enough.’ It is beginning, not ending, on 25 September,” the organizer says.

The Surround the Congress campaign began two months ago in the form of citizens’ assemblies, held mostly online and in Retiro Park in Madrid.

“Nobody launched it — it emerged and was a success. It was a totally distributed decision,” says Antonio, a young activist who prefers not to give his real name, as a means to reject a position of leadership.

Antonio, like Sanchez, traveled to Madrid last weekend to participate in the protest, which brought thousands to the streets on Tuesday.

The protest does not aim to prevent MPs from accessing the building or interfere with the normal activity of the parliament, but is nonetheless discomfiting for the conservative government of Mariano Rajoy, whose People’s Party triumphed in November elections.

Four people were detained during another demonstration next to the Prado Museum last week; they were holding a banner referring to the planned Surround the Congress protest.

Around 1,300 police were deployed to defend Congress on Tuesday.

“From the beginning, they tried to criminalize us. What they want is to scare the people, but what is happening is the opposite: More people are joining,” explains a member of the organizing group. Speaking to Egypt Independent last week, Antonio was concerned that police might try to provoke protesters to fuel confrontation.

During the event, at least 34 people were arrested and 64 injured, including 27 policemen.

Social media is another strong feature of the 15-M movement. Antonio is among those who actively use social media as a tool to organize, coordinate and spread news in real time.

But the government is moving to restrict online organizing. Its proposed reform of the Spanish Penal Code contains a new article that would make it an offense to contribute to the disruption of public order through using the Internet.

“The goal is to create a new offense, supporting street protests on the Internet, so that people would be afraid to express themselves freely on Twitter,” says well-known lawyer Carlos Sanchez-Almeida, a specialist in Internet freedom.

The new technologies, as Subirats points out, seem to be responsible for this new way of doing politics, with a distributed, less mediated structure. It’s a structure, he says, that defined the Arab revolutions, the 15-M movement and others which followed, such as the Occupy Movement in the US and “I’m 132” in Mexico.

“What is new about 15-M is that instead of asking the political system to change, it considers that the system and the politicians are the problem — that is, the demand is about the way of doing politics,” he says. “One era is changing into another now, it is called crisis but it is not, and it cannot be explained without the Internet.”

The older activists who make up Iaioflautas combine some of the tools they learned to use in the anti-Franco era — labor unions and local or left-wing fights — with new technology.

“Technology has accelerated and changed everything, but the objectives are the same: a society in which we as people can live freely, in which we can have homes, transportation and in which we can study,” says Celestino Sanchez. “This is what we wanted 30 years ago, and it continues to be the case.”