When the United States withdrew its forces from Afghanistan after 20 years in the country, it did so on a promise that the Taliban once back in government would provide no haven for terrorist groups.

The Taliban pledge covered not only al Qaeda – the terror group whose presence in the country led to the US invasion in 2001 – but also the Taliban’s ideological twin next door, the Pakistani Taliban or TTP (Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan).

But the recent break down of an already shaky year-long ceasefire in neighboring Pakistan between the TTP and Islamabad raises some troubling questions over whether that promise will hold.

The end of the ceasefire in Pakistan threatens not only escalating violence in that country but potentially an increase in cross-border tensions between the Afghan and Pakistani governments.

And it is already putting links between the Afghan Taliban and its Pakistani counterpart under the spotlight.

As recently as spring last year Pakistani Taliban leader Noor Wali Mehsud told CNN that in return for helping to push the US out of Kabul his group would expect support from the Afghan Taliban in its own fight.

Like their erstwhile brothers in arms in Afghanistan, the Pakistani Taliban want to overthrow their country’s government and impose their own strict Islamic code.

In an exclusive interview with CNN this week, Mehsud blamed the ceasefire’s breakdown on Islamabad, saying it “violated the ceasefire and martyred tens of our comrades and arrested tens of them.”

But he was more guarded when asked directly whether the Afghan Taliban was now helping his group as he had once hoped.

His answer: “We are fighting Pakistan’s war from within the territory of Pakistan; using Pakistani soil. We have the ability to fight for many more decades with the weapons and spirit of liberation that exist in the soil of Pakistan.”

Those words should be of concern not only to Islamabad, but Washington too.

The FBI has been tracking the TTP for at least a decade and a half, long before they radicalized and trained Faisal Shazad for his brazen attack setting fire to a vehicle in New York’s Times Square in 2010.

Following the Times Square attack the TTP was designated a terrorist organization and is still considered a threat to US interests.

And while Islamabad is keen to play down the threat from the group – Interior Minister Rana Sanaullah says Pakistan can “fully” control conflict with the TTP and describes conversations with the TTP during the ceasefire as talks “which are held in a state of war” – its control of the situation pivots on the TTP remaining within Pakistan’s borders.

Attacks raise questions

There are growing questions about the TTP’s reach and Islamabad’s perception of the situation does not match Mehsud’s.

In April this year, the Pakistani military struck targets in Afghanistan warning that “terrorists are using Afghan soil with impunity to carry out activities inside Pakistan.”

And in late November, the day after the ceasefire broke down, Islamabad again claimed the TTP were using Afghan territory as a safe haven, sending Foreign Minister Hina Rabbani Khar to express its concerns to Kabul.

The very next day the TTP claimed responsibility for an attack in the border province of Quetta, where a suicide bomber had targeted a police van helping a Polio vaccination team, killing three and injuring 23.

When CNN pressed Meshud on Islamabad’s claims that he is getting Afghan help, asking him if the support is being kept secret, he rejected this, saying: “When we don’t need any help from the Afghan Taliban; what is the point of hiding it?”

Nevertheless, cross border Afghan/Pakistani government tensions are building and came to a deadly head again last week in an exchange between the two countries’ militaries near the Chaman/Spin Boldak border post, a vital commercial link between the two countries.

Six people were killed and 17 injured. While there is no evidence of direct involvement by the TTP – or at least, not yet – the end of the ceasefire has clearly raised the temperature.

The situation is only getting more combustible, with the TTP this week announcing another three jihadi groups had joined their ranks, all from along the troubled Afghanistan-Pakistan border region.

America versus the TTP?

The United States has also accused the Pakistani Taliban of using Afghan territory, doing so in a statement three days after the ceasefire ended in which the State Department named TTP defence chief Qari Amjad as a “Specially Designated Global Terrorist.”

That raises the possibility that the US could target TTP commanders found operating in Afghanistan – much as it killed al Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri with a drone strike in Kabul in September.

“The United States is committed to using its full set of counterterrorism tools to counter the threat posed by terrorist groups operating in Afghanistan, including al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent and Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), as part of our relentless efforts to ensure that terrorists do not use Afghanistan as a platform for international terrorism,” the State Department said in its statement.

Intriguingly, the Pakistani Taliban is the only terrorist group in the region to have acknowledged al-Zawahiri’s killing.

Yet in his interview with CNN, Mehsud was defiant saying he “did not expect America to take such action” against his group.

“America should stop teasing us by interfering in our affairs unnecessarily at the instigation of Pakistan – this cruel decision shows the failure of American politics,” he said.

But he also shot back with a threat, that “if America takes such a step, America itself will be responsible for its loss. The United States has not yet understood Pakistan’s duplicitous policy; Pakistan’s history is a witness that it keeps changing directions for its own interests.”

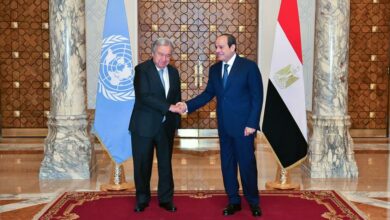

Washington, for its part, faces a quandary. Pakistan’s Foreign Minister Bilawal Bhutto is currently visiting the US and the TTP was likely on the agenda when he met United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres for a Security Council debate on the “maintenance of international peace and security” on December 14. It will also likely feature in his talks with US administration officials in Washington, DC, which are scheduled for December 19.

But as the United States has already discovered at its cost, there are no easy solutions in Afghanistan.

More than a year since its withdrawal and the humanitarian situation in the country continues to worsen, and despite the US recently easing controls that limit the Afghan Taliban’s access to international funds, the former terror-group-turned-government continues to fail even moderate international expectations of good governance.

The UN Human rights chief recently accused the Afghan Taliban of “the continued systemic exclusion of women and girls from virtually all aspects of life”, and in the past week they held their first public execution since coming to power.

Yet if the Afghan Taliban are shown to be helping the TTP, there is another troubling prospect for the US: it may face greater pressure to re-engage.