As the first anniversary of the Egyptian revolution approaches, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) is continuing to issue shrill warnings of a plot to topple the state. The most direct came from Field Marshal Hussein Tantawi himself, when he said last week, "Egypt is facing grave dangers it has not seen before." He added, "The armed forces are the backbone that protects Egypt. These schemes are aimed at targeting that backbone."

Tantawi is right. There is a plot to topple the state. Egypt's revolution has evolved from an uprising that ousted President Hosni Mubarak into a deeper struggle aimed at uprooting the military regime that has ruled the country for the past 60 years and served as the backbone of its modern autocracy. Since 1952, the army has enjoyed a special autonomy in Egypt, both political and economic, above any civilian control or oversight. It is this very autonomy and privilege that the revolution is now targeting and has the military council talking of a threat to destabilize the country.

Over the past few decades, the army has burrowed itself ever deeper into Egypt's economy, building a sprawling business empire that utilizes a mass conscripted labor force and includes vast real estate holdings in the north and on the Red Sea coast. Army divisions make everything from television sets and off-road vehicles to olive oil, bottled water and fertilizer. Estimates of the military's share of the economy vary widely, ranging from 15 to 40 percent of gross domestic product, a testament to the cloak of secrecy that conceals their financial affairs. Meanwhile, senior army officers live a life apart in self-contained military cities, complete with their own housing, sports teams and supermarkets selling foreign goods at a discount.

Since Gamal Abdel Nasser and the Free Officers overthrew the pro-British monarchy in 1952, every president — not to mention many governors, ministers and other senior civilian positions — has been drawn from the top ranks of the armed forces. In Nasser's era, the military was a regular presence in the daily lives of Egyptians, arresting and torturing dissidents while police forces played a relatively minor part. After the military defeat of 1967, Nasser's death and Anwar Sadat's rise to power, the army began to retreat from public view while state security forces grew to play a larger role in suppressing dissent. This trend continued under Mubarak until the military eventually became a shadowy element in public life and a silent partner to the dictatorship.

The 2011 revolution reversed that phenomenon and brought the military back to the forefront of the political sphere. The army was the first deployed to Cairo and cities across Egypt last year on 28 January, perhaps the most decisive day of the revolution yet, when millions of Egyptians flooded the streets in unprecedented numbers and overwhelmed the Interior Ministry's security forces within a matter of hours.

The military enjoyed widespread praise as "the protector of the revolution" and was applauded for not opening fire on protesters, a dubious accolade in and of itself. Chants of "The people and the army are one hand" were ubiquitous in Tahrir Square during the 18-day uprising. In the days and weeks that followed, any criticism of the military generally, or the SCAF in particular, was widely denounced as heresy.

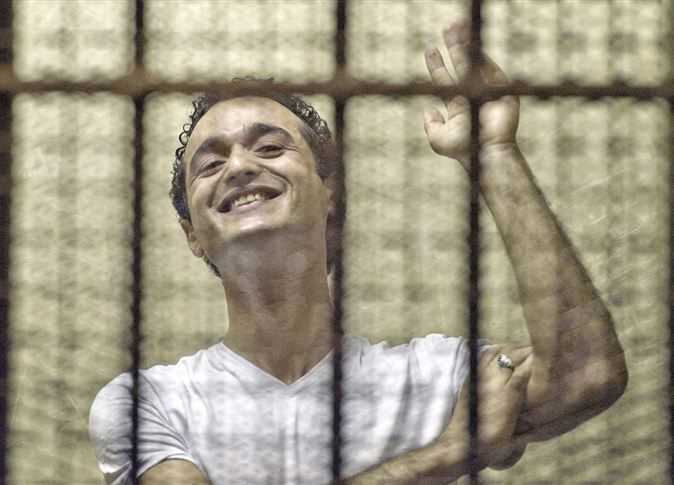

But the afterglow has since faded away. Over the past year, the military has killed, wounded, imprisoned and tortured protesters. The single bloodiest day since Mubarak's ouster came at the hands of the army — not Interior Ministry forces —when soldiers fired live ammunition and drove armored personnel carriers into a crowd of Coptic protesters and their supporters, killing 27 people. The December clashes centered on Qasr al-Aini Street marked the longest sustained battle between protesters and the army since the revolution began and will be forever remembered by the notorious image of three soldiers dragging and stomping on an unarmed woman.

Meanwhile, erratic and confusing decision making by the SCAF throughout the transitional period combined with its complete denial of any wrongdoing and high-handed attitude toward any criticism has done serious harm to its legitimacy. Namely, the military leaders have seemed unwilling to govern and unwilling to let anyone else do so.

While the revolution may have brought the SCAF to the helm of political power, over the past 12 months it has grown to challenge the military's dominance within the state. Despite increasing levels of state-backed violence, the protest movement has continued its resistance, helping to bring the political elite and the greater body politic out of paralysis to begin confronting issues that were formerly taboo. Transparency and oversight of the military budget are now openly discussed, the army's annual receipt of US$1.3 billion in annual military aid from the US is being questioned, and even notions of a civilian defense minister are being cautiously whispered.

That's not to say any of these policies will be changed anytime soon. The army, backed by a dutiful state media apparatus, still enjoys widespread support and is working hard to engineer a handover of government back to a civilian authority that would preserve its special status. The post-Mubarak lower house of Parliament, the People’s Assembly, is dominated by the Muslim Brotherhood, a group that has sought to avoid confrontation with the military council at every juncture over the transitional period. The People's Assembly convened for the first time on Monday behind four walls the army has erected in the heart of the capital, shielding the main institutions of government from Tahrir, the epicenter of the revolution.

While the SCAF remains in a relatively comfortable position, its continued warnings about a growing threat to the state is the revolution beginning to knock at their door.

Sharif Abdel Kouddous is an independent journalist based in Cairo. He is a correspondent for the TV/radio show Democracy Now! and a fellow at the Nation Institute.