While state employees have historically shied away from street politics, some have begun to engage in protests in front of key government agencies over the last four years.

In the wake of the 25 January uprising, employees in many sectors–including state-owned publishing houses and the supply directorate (rations)–took to the streets for the first time. While their demands were primarily economic, they also included pleas against corruption and nepotism.

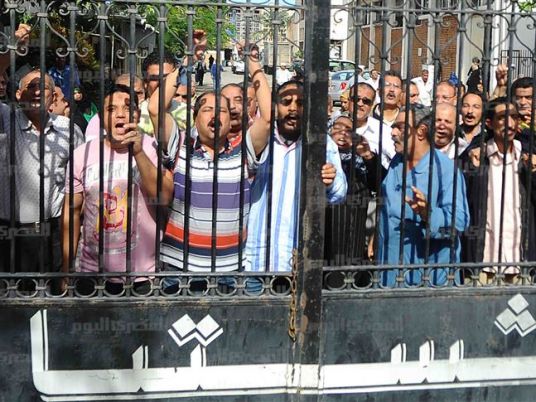

In the last few days, Cairo's Kasr al-Aini Street has formed a nexus of labor dissent. On 14 February, around 90 employees from Cairo’s Directorate of Supply, along with employees from other governorates, organized a demonstration in front of the Council of Ministers building.

On 13 February, approximately 70 employees of the Dar al-Shaab Foundation, a state publisher, staged a protest in their office courtyard. Also, a group of journalists from Al-Massa’iya newspaper are continuing to take legal measures to contest what they say was their unfair dismissal.

These protests are taking place despite the current military government’s attempts to persuade the Egyptian public to leave the streets and return to business-as-usual. Analysts say public sector employees are capitalizing on the momentum brought about by the large-scale popular uprising that ultimately led to the resignation of longstanding President Hosni Mubarak on 11 February.

Although protesters have clear economic grievances, they primarily lament what they perceive as unfair procedures, either in regard to unequal pay among employees of various government institutions or the arbitrary dismissal of workers. Supply employees also complain of the government’s failure to implement a court-mandated, LE1200-per-month minimum wage, pointing out that those with 25 years of working experience still often earn only LE450 per month.

Beyond this, protesters have also taken steps to expose corruption at the higher levels of administration, sometimes implicating longstanding regime officials.

Protesters’ most prominent demand, however, is for employees to receive pay and benefits equal to those of employees with similar jobs in other government agencies. “Employees of the Ministry of Social Solidarity receive 250 percent in bonuses, while we get a mere 75 percent,” says Mohamed Abdul Fatah Mohamed of the Cairo Directorate of Supply.

Employees of the Dar al-Shaab Foundation, meanwhile, demand that they be paid on an equal basis with employees of the National Company. They say that many of them earn only LE400 per month, while their colleagues in the National Company earn thousands.

Notably, the assets of Dar al-Shaab and Dar al-Ta’awun, another state publisher, were merged in May 2009 into the National Company. The merger conditions mandated that all employees and journalists would retain their jobs and their rights. But employees of both institutions argue that these conditions have been completely ignored.

Their second major concern has to do with the arbitrary dismissal of employees and the failure to honor agreements concerning hiring and firing. Dar al-Shaab employees complain that, following the merger, the National Company pressured employees to leave by forcing them to accept early retirement packages, and that the administration used several unfounded pretexts to arbitrarily dismiss fixed-contract employees. They point to the fact that only 500 employees–out of an original 1200–still have their jobs.

“Chairman Bahghat Hassan has refused to make new hires, even though the state mandated that all those with contracts should be hired,” said one Dar al-Shaab employee.

Dar al-Shaab employees also lament the fact that the National Company administration has imposed all the negative sanctions mandated by the merger–such as the cancellation of seven days emergency vacation–without granting them any of the benefits.

Beyond these grievances, protesters are also taking steps to expose and document alleged corruption in their respective institutions. Dar al-Shaab employees, for example, claim there is rampant corruption in the National Company, with some pointing out that National Company members received 12 months worth of profits and chalets worth some LE 18 billion.

Similarly, a group of Al-Masa’iya journalists is planning to file a complaint to the Attorney General against newspaper editor-in-chief al-Rashidi and officials of the ruling National Democratic Party on the grounds that they sold land belonging to Dar al-Ta'awun for one third of its true value in early 2009.

“We intend to take the necessary steps to stop corruption in the institution and put an end to the theft of public funds,” said one dismissed journalist, who preferred to remain anonymous.

After 25 January, many workers and government employees who felt repressed before are now finding the courage to express themselves, says Kamal Abu Eita, head of the Independent Union for Tax Collectors. The tax collectors union, formed in 2008, represents Egypt's first independent syndicate for state-employees.

Abu Eita attributes the haphazard nature of the current round of labor protests to the absence of a representative union system in Egypt. “Those who want to stop these protests should open the door to independent unions,” he says.