Many of Iraq’s Egyptian migrant workers share a similar sentiment, looking back on their time in Iraq with fondness and nostalgia.

A popular tale that speaks to migrants’ close association with the country tells of an Egyptian worker who was arbitrarily blamed by a wealthy Iraqi for dirtying the latter’s brand-new car. The Iraqi proceeded to beat the Egyptian, until, by chance, Saddam Hussein — who just happened to be driving by — intervened, sending the Iraqi to prison and handing the Egyptian a match to set the car alight.

Far-fetched as it sounds, this is one of the many urban myths circulated among the at least 1 million Egyptians who worked in Iraq two decades ago, prior to the series of invasions, sanctions and occupation that has since kept them out.

Ten years after the second US invasion, Egyptians who worked there share their memories about the country and its effect on their lives.

Lasting memories

Mohamed Abdel Gawad, a 48-year-old microbus driver from Minya, left Iraq after Iraqi troops invaded Kuwait in 1990. He says he tried to return, but has not been able to because the situation there is still too dangerous.

He worked there as a truck driver on a route between Ramadi in western Iraq and Basra in the south. Iraqi food, in particular, has not left his memory, he says, fondly recalling a roadside restaurant he frequented along his route.

While talking about the relationship between Egypt and Iraq, he stops and holds up his finger.

“You know, I wanted to marry my landlord’s daughter,” he says. “I loved her, she loved me. But when Saddam invaded Kuwait, I thought of returning to Egypt because the situation was quickly deteriorating.”

Had the country been safe enough to work in for the past 20 years, Abdel Gawad says, his life and those of many other Egyptians would be very different.

Many express anger toward the US government for initiating its long war in Iraq, and for the continued state of violence and danger in the country.

Saddam’s dictatorial state brutally suppressed marginalized Iraqis such as Kurds and Shias, particularly during the 1991 uprisings in the country’s north and south, as well as others who opposed or posed a threat to his regime. Bodies of Iraqis who were killed during this time have turned up more than a decade later in mass desert graves.

But while many Egyptians who worked in Iraq acknowledge such suppression, they also remember the autocrat’s affection for Egypt, a country where he lived in exile for four years and which played a prominent role in his political ideology. Saddam is said to have once declared that anyone who caused problems for Egyptians caused problems for him.

In one telling scene toward the end of the 1980s, Saddam appeared on television, visiting an Egyptian family in Baghdad. He spoke with the family, enquiring after their living situation and opened their refrigerator to ensure they had food.

While there are those Egyptians who express admiration for Saddam and tend toward his brand of pan-Arab nationalism, others feel an affinity toward Iraq because of their adherence to Shia Islam, which the majority of Iraqis but only a small number of Egyptians, practice.

Mahmoud al-Shibra of Assiut named his son Haydar, a common name in Iraq, especially among Shias in Karbala, where he worked in construction for five years, eventually saving enough to marry and buy a home.

Now 53, Shibra works for a tourism company. He returned to Egypt after the 1991 Gulf War.

The Egyptian economy lost a lot of support when workers returned, he says. Faced with a more difficult living situation in his native country, Shibra traveled to Libya and to the Gulf, but claims not to have received the same treatment as in Iraq.

The path to Iraq

Two main factors opened the door for Egyptians to work in Iraq. First was a gradual easing of Egyptian migration policies from the 1950s to 1970s. Second was the Iran-Iraq War.

The Egyptian government may have viewed relaxed migration policies as a win-win situation. Egyptian workers abroad would have the opportunity to earn more money for their families, while remittances would help boost foreign currency levels and opportunities in foreign markets could help ease unemployment and overcrowding.

Hassan Ahmed Obeid, economics professor at the Cairo University Faculty of Economics and Political Science, says Iraq was the highest source of remittances for Egypt in the 1980s, and, as such, “played a huge role in Egypt’s economy.”

In September 1980, Iraq attacked Iran after a series of border disputes and amid fears sparked by the recent — ideologically Shia — Islamic revolution. The eight-year war forced masses of Iraqis to fight and resulted in a diminished workforce.

Estimates of the total number of Egyptian laborers in Iraq during the 1980s vary greatly, ranging between 1.25 million and 5 million.

According to Egyptian Foreign Ministry estimates compiled by economic cooperation expert Gil Feiler, by 1983, the number of Egyptian migrant workers in Iraq had reached 1.25 million, compared with 50,000 in 1978.

State-owned newspapers in Iraq and Egypt — without specifying a particular year — put the number during the 1980s at 3 million and 5 million, respectively, though it is also unclear whether these numbers account only for migrant workers.

Notably, Al Jazeera reported that in the late 1980s, 42 percent of Egyptian workers abroad were based in Iraq.

Osama Tawfiq, administrative representative from the Egyptian Consulate in Baghdad, says the consulate has no exact figures on the number, adding that the 2003 war disrupted its services and it no longer has these records. Representatives from the embassy in Baghdad and the Egyptian Foreign Ministry also could not verify the information.

Estimates also vary for the number of Egyptians in Iraq now, with sources citing figures ranging from 25,000 to 150,000. But only 116 Egyptians registered to vote from the country during last year’s presidential election, according to the Egyptian Foreign Ministry.

During the Iran-Iraq War, some Egyptians volunteered to serve in the Iraqi army. Feiler estimates that Egyptians comprised about 50 percent of foreign Arab fighters during the war — putting the number of Egyptian fighters at between 12,000 and 15,000.

Among those fighters was Ali Ismail Ali, 56, who now runs a small hotel in the coastal Sinai city of Dahab. He says he fought in the Nasrat al-Arouba brigade with other Arab fighters.

With Egypt’s tourism sector still facing difficulties after two years of political upheaval, Ali feels nostalgic about Iraq. He lived there for seven years, and worked in Basra as well as Baghdad.

Shahin, who worked as a cook alongside Ali in Sulman Bak, a neighborhood in southeast Baghdad, also volunteered in the war.

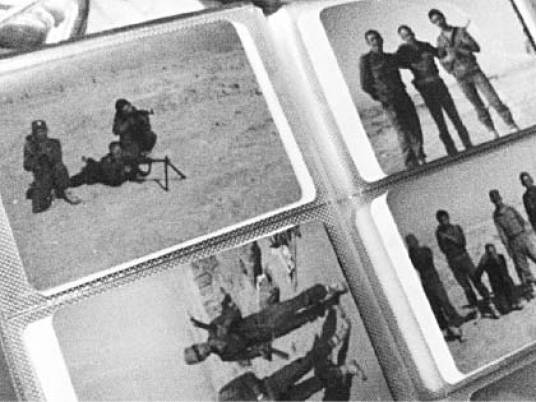

He carries around a keychain made from an Iraqi coin and treasures a commemorative military magazine from his time in the army, as well as a photo album with images of himself and other uniformed fighters.

With the 1988 cease-fire, mistreatment of Egyptian workers increased as Iraqis came back from the war. By 1989, news reports indicate that thousands of Egyptian workers began leaving Iraq.

The exodus continued with the start of the Gulf War a year later. Egypt’s participation in the US-led coalition force fighting Iraq worsened already testy relations between the two countries.

Following the invasion, the UN imposed economic sanctions, which proved catastrophic for migrant workers.

“The flow of Egyptian workers to Iraq stopped and the flow of remittances to Egypt stopped, so this siege affected Egypt dramatically,” Obeid says.

More than half a million workers are still waiting, more than a decade later, to receive US$409 million in remittances, according to an Egyptian joint-government committee.

Yet Ali still fondly remembers and lists the names of his Iraqi friends, though he hasn’t been in contact with them since he left. He says he feels sure that if the situation in Iraq improved, many Egyptians would choose to return.

“I wish, by God, I could return to Iraq,” Ali says, repeating “I wish, by God” three more times.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.