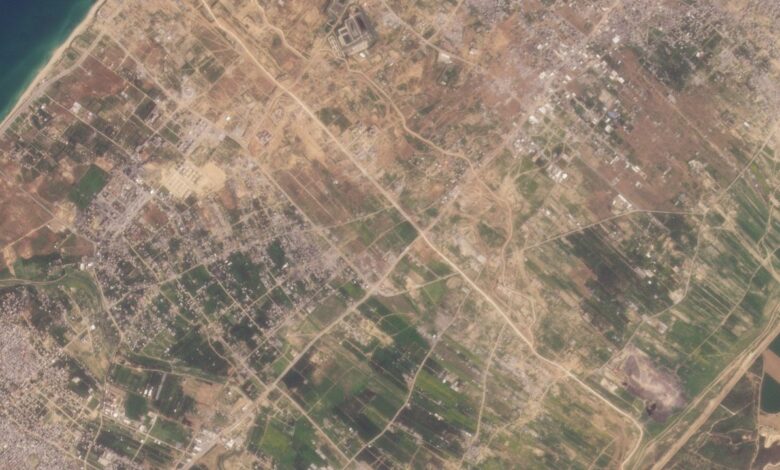

A satellite image from March 6 reveals that the east-west road, which has been under construction for weeks, now stretches from the Gaza-Israeli border area across the entire roughly 6.5-kilometer-wide (about 4-mile-wide) strip, dividing northern Gaza, including Gaza City, from the south of the enclave. About 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) includes an existing road, while the rest is new, according to CNN’s analysis.

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) told CNN they were using the route to “establish (an) operational foothold in the area” and allow “the passage of forces as well as logistical equipment.” When asked about the route’s completion, the IDF said the road existed before the war and was being “renovated,” due to armored vehicles “damaging it.” It added that there was: “No beginning and ending.”

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu unveiled a plan, obtained by CNN, to his security cabinet on February 23 for a post-Hamas future for Gaza, including the “complete demilitarization” of the enclave, and the overhaul of its security, civil administration and education systems. Palestinians living in Gaza fear Israel’s post-war security plans will further restrict their freedom of movement, remembering the days of Israeli occupation prior to 2005, when checkpoints were placed between neighboring villages and exclusive bypass roads were built to link Israeli settlements to each other and to Israel.

Named after the former Israeli settlement of Netzarim in Gaza, the “Netzarim Corridor” intersects one of Gaza’s two main north-south roads, Salaheddin Street, to create a strategic, central junction. It also appears to connect with Al Rashid Road, which runs along the coast, satellite imagery shows. Palestinians told CNN that they remember the so-called “Netzarim junction” existed before 2005; back then, it was largely only accessible to Israeli settlers.

Israeli Minister for Diaspora Affairs Amichai Chikli told CNN that the new road will “make it easier” for the Israeli military to launch raids north of Gaza City and south, to the central area of the Gaza Strip.

The road, which he said will be used for at least a year, will have three lanes: one for heavy tanks and armored vehicles, another for lighter vehicles and a third for faster movement. It will be possible to drive on the Netzarim Corridor from Be’eri, an Israeli kibbutz near the Gaza border, to the Mediterranean Sea in seven minutes, he said.

Chikli is not involved in Israeli military policy. But, in January, Chikli, along with other members of Israel’s parliament, the Knesset, proposed a plan to defeat Hamas that included steps to gain control over strategic parts of the strip. In it, they said that the Netzarim Corridor would be used “to enable treatment of the underground infrastructure of Hamas and its resistance pockets in the north of the Gaza Strip.”

“The residents of the Gaza Strip should not be allowed to return to the north at least until the demolition of all the underground infrastructure and the complete demobilization of the area,” they said in the proposal. It also included a second corridor further south that he called the Sufa Corridor. The plan has not been adopted by the IDF, but it includes elements that are coming into existence, including the Netzarim Corridor.

Cutting the strip in two

A series of satellite images from before and after October 7 show how Israel is extending an existing road to build the corridor. An image from February 29, provided by Maxar Technologies and reviewed by CNN, shows newly bulldozed sections of road to the east and the west of the existing one. And the satellite image from March 6, provided by Planet Labs, shows the new construction reaching all the way to the coast.

The Israeli military began bulldozing a path for its armored vehicles soon after declaring war against Hamas on October 7, following the militant group’s attack on Israel. Satellite imagery from November shows the tracks emerging, at a time when the military’s focus turned to surrounding Gaza City, advancing from the east. In early October, Israel ordered the evacuation of 1.1 million people from northern Gaza to south of Wadi Gaza, a strip of wetlands bisecting the enclave.

The Israeli military gave right-wing Israeli TV Channel 14 a tour of the Netzarim Corridor in February, revealing what it called a “buffer” that is being worked on around the road. The report showed forces from the Israeli Engineering Corps operating tractors, trucks and engineering tools.

Lt. Col. Shimon Orkabi, commander of Battalion “601” of the Combat Engineering Corps, told Channel 14 that the soldiers were busy destroying any remaining infrastructure in the buffer area. “It basically opened up this entire space of territory to us, allowing us to control everything that happens in this corridor,” he said.

He added that the Israeli military used a “large amount of mines and explosives” to demolish buildings in the buffer zone, and that the remaining buildings in the area will “probably disappear soon.”

The Channel 14 report shows the Turkish-Palestinian Friendship Hospital, about 380 meters (about 1,240 ft) away from the road, partly in ruins and soldiers operating in the area.

In a video shared on TikTok, geolocated and verified by CNN, Israeli soldiers can be seen destroying what appears to be the entrance of the Turkish-Palestinian Friendship Hospital. Posted by an Israeli soldier on the social media platform on February 22 and since deleted, the video also shows troops in an armored vehicle driving into the medical complex.

The IDF told CNN it had destroyed part of a “tunnel network” beneath the Turkish-Palestinian Friendship Hospital, which it claimed was “connecting the north and south of the Gaza Strip.”

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk said in February that the IDF’s reported destruction of residential buildings and other civilian structures elsewhere in the Gaza Strip, within a kilometer of the Israel-Gaza fence to create a buffer zone, could amount to a war crime.

‘A barrier of humiliation’

Emily Harding, director of the Intelligence, National Security, and Technology Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, DC, told CNN that the Netzarim Corridor is an attempt “to control population movement.”

A road splitting the strip will make it easier to “screen people moving back and forth between the north and south and try to figure out if any of them are Hamas fighters,” she added.

Harding said Israel’s biggest challenge since they started the operation in Gaza is to try to root out Hamas militants hiding amongst a civilian population: “The only way you do that is with really good tactical on the ground intelligence, and then preventing them from actually moving around.”

Many people in Gaza remember what such controls on movement were like before Israel withdrew from the strip.

During a Palestinian uprising against the Israeli occupation from 2000 to 2005, known as the Second Intifada, the so-called “Netzarim junction” was closed off entirely, Jamal Al-Rozzi, a teacher from Gaza City, told CNN. It became known as a hotspot for clashes between Palestinians and Israelis, he said.

“Israeli soldiers were stationed at the junction full-time, and because Israeli settlers used it, we Palestinians mostly could not,” he said.

During this period, Israel tightened its “internal closure” policies, mostly for the security of settlements, according to a 2004 Human Rights Watch (HRW) report, leaving only one route between the northern and southern halves of the Gaza Strip. Along this route were the Abu Holi and Matahen checkpoints, which severely limited movement.

“The Abu Holi checkpoint was notorious,” Al-Rozzi said, recalling a route from Gaza City to the southern city of Khan Younis that “took days” to travel.

“They placed a traffic light there that would only turn red. From red to red. Can you imagine? I remember it vividly.”

Abu Holi was seldom open, Munther Al-Ashi, a lawyer from Gaza City, told CNN. He grew up there and recalls the “almost impossible” movement along the checkpoint in the early 2000s. “It was a barrier of humiliation.”

“I remember at that time my brothers and I were selling clothes. We used to go out very early in the morning to head southward. The checkpoint would be open sometimes, but on the way back, we would spend eight or nine hours on average. Sometimes it would remain closed, and people would spend their nights in the streets,” he said.

“The memories of that checkpoint are painful,” he said. “Imagine 200 to 300 cars waiting at the checkpoint to be granted passage by Israeli soldiers.”

The Israel-Hamas war has displaced both Al-Ashi and Al-Rozzi from the north to the southern city of Rafah.

“If our house in Gaza City has not been shelled, I would like to go back to it. How am I going to do that if there are gates and checkpoints in my way?” Al Rozzi said.

“More so, how do we function there if I manage to cross back in? Will there be infrastructure left? Roads I can use?” he said. “I am a teacher. Will there be schools I can teach at? Am I going to be able to access them?”

CNN’s Ibrahim Dahman and Gianluca Mezzofiore contributed to this report.