The scene looks almost post-apocalyptic. A convoy of Russian soldiers emerging from thick fog and moving towards the eastern Ukrainian city of Pokrovsk. Some of the troops are riding motorcycles and mopeds; others are seen standing up on the back of a dilapidated pickup truck. One group is riding a vehicle equipped with a strange cage-like contraption.

As bizarre as it seems, the short video clip, which was posted on social media and geolocated by CNN to just a few miles outside Pokrovsk, offers a glimpse of the shifting ways Russia is fighting its war in Ukraine.

If Pokrovsk falls to Russian forces, as now looks increasingly likely, it will be the largest city seized by Moscow since the capture of Bakhmut in May 2023.

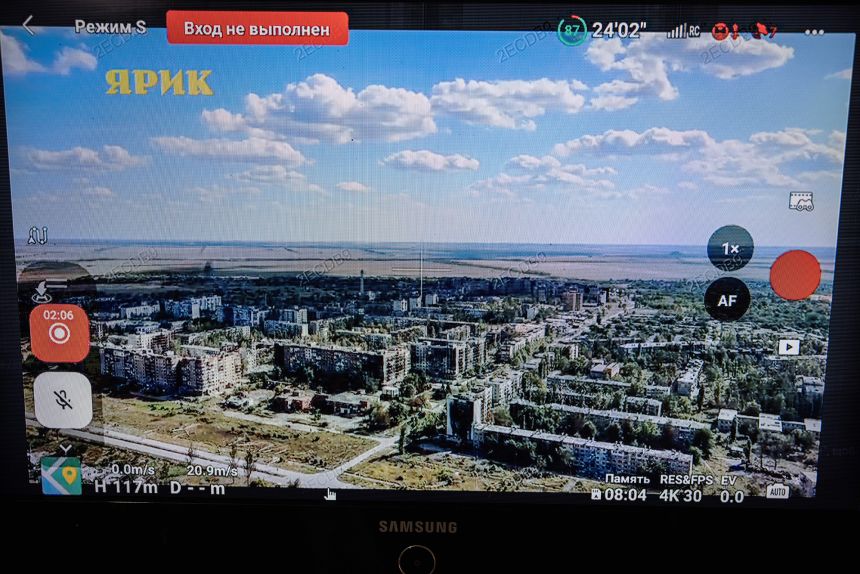

Like Bakhmut, Pokrovsk has been mostly reduced to rubble, and its strategic importance is now greatly diminished. But like Bakhmut before it, Pokrovsk has also become a symbol of Ukraine’s resistance.

That’s why Russian President Vladimir Putin seems prepared to pay almost any price for it – and why the Ukrainian army keeps trying to hang onto it even though the situation is becoming increasingly desperate.

While the fate of the two eastern towns might look very similar, soldiers on the ground, military observers and analysts say the way Russia has approached them is very different – and the change in tactics tells a story of how the war has evolved over the past two years.

The main reason for the transformation is the massive proliferation of drones, with recent technological advances making it possible to deploy many more of them across much larger distances. This has effectively extended the “kill zones” on either side of the front line between Russian and Ukrainian troops, making battlefield advances much more difficult.

Rather than using heavy armor to push through by force, Russian troops are increasingly looking to infiltrate Ukrainian areas with unconventional vehicles like mopeds and four wheelers.

One soldier from Ukraine’s 129th Brigade who is currently deployed near Kostiantynivka, northeast of Pokrovsk, told CNN that his unit’s first encounter with Russians on buggies was “extremely unexpected” but nevertheless made sense.

“It’s logical. We strike with drones, and it’s easier (for them) to move around (using) light transport,” the soldier said. He asked to remain anonymous because of security concerns.

The Ukrainian Ministry of Defense said on Tuesday that some 300 Russian troops were now estimated to be inside Pokrovsk, although it stressed that the fight was still ongoing.

Medical evacuations become impossible

Russia has been slowly advancing on Pokrovsk for nearly two years, after the breakthrough at Avdiivka further east in early 2024.

Mason Clark, the director of the Defense of Europe Project at the Institute for the Study of War (ISW), a Washington-based conflict monitor, told CNN that, just like the capture of Avdiivka, Russia had advanced to Pokrovsk “in order to force Ukrainian troops to eventually withdraw, or ideally encircle Ukrainian forces completely.”

“That is different from Bakhmut, which was much more of a grinding, direct frontal assault into urban terrain on purpose. (In Pokrovsk) the operational goal has been to surround the Ukrainian troops, rather than necessarily clear the city block by block,” he said.

While Moscow’s forces haven’t completely surrounded Pokrovsk, they have managed to sever Ukrainian supply lines.

One Ukrainian combat medic whose unit is currently fighting in Pokrovsk and the nearby town of Myrnohrad said extractions from the city are currently nearly impossible, with evacuation vehicles unable to get any closer than 10 to 15 kilometers (6 to 9 miles) from the city – and even that proximity remains extremely risky because of the drones.

“The seriously wounded don’t make it to the (medical) stabilization point. If someone (sustains) a moderate injury, they will arrive to me in serious condition, if they are lucky enough to make it at all. Minor injuries arrive as moderate,” he told CNN. He asked for his name not to be released because he is not authorized to speak to media.

“Right now, we have several people who have been in position with serious injuries for two weeks. There is one who has been in serious condition for a week, and we can’t get him out,” he added.

The Ukrainian military has been trying to use unmanned armored vehicles to extract casualties, but the medic working in Pokrovsk said that the vehicles attracted a huge amount of Russian fire – even though international law forbids attacks on unarmed and clearly marked medical transports.

Small groups sneaking in

The battle of Bakhmut in the first half of 2023 was marked by what the Ukrainians dubbed “meat grinder” assaults, in which waves of Russian troops would keep coming towards well-defended Ukrainian positions. The idea was that as Ukrainian troops opened fire, they would reveal their positions.

The tactic led to extremely high casualty rates among Russian troops who were essentially being sent forward to be killed. Those who wanted to turn back risked the threat of being shot by their own superiors.

Ukrainian soldiers fighting in Bakhmut told CNN of killing dozens of Russian personnel every day, their bodies left to freeze in the fields, as another wave of troops was sent on the same mission the following day. Eventually, by sheer weight of numbers, this Russian approach did work, exhausting the Ukrainian military after months of fighting.

Now though the tactics have shifted.

“In Bakhmut, the Wagner group would send personnel out in the open to draw Ukrainian fire, expecting them to be killed … now the intent is for as many of these personnel to get close to Ukrainian positions as possible. They’re not being sent out in order to be killed,” said the ISW’s Mason Clark.

The soldier from 129th Brigade old CNN that the Russian assault groups have also become smaller.

“In urban areas, they used to move around in groups of five to seven people. Now it’s a maximum of three. But they are difficult to track with reconnaissance drones, because there is less movement on the screen,” said the soldier, who asked not to be identified for security reasons.

Another fighter, from the Ukrainian ‘Peaky Blinders’ drone unit also said the Russians often move in groups of three, adding that attrition rates remain high. “(They are) counting on the fact that two will be destroyed, but one will still reach the city and gain a foothold there. About a hundred such groups can pass through in a day,” he told CNN last week, speaking on condition of anonymity.

The UK’s Ministry of Defence estimates that of the more than 1.1 million casualties Russia has suffered since it launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, a third were killed or wounded this year.

“This is feasible for the Russians because they’ve accepted a very slow pace of advance, and this sort of operational approach does move very slowly, whereas back in 2022 and 2023 they were still putting more of a premium on advancing quickly,” Clark said.