Safa Babikir was sleeping in her aunt’s house in Khartoum when she was woken by gunfire. At first, she thought it was the sound of children playing with fireworks. Then, she says, “the screams started.”

Desperate to escape the fierce fighting in Sudan’s capital, Babikir soon made a decision to flee the country on a treacherous bus journey to neighboring Egypt.

The 28-year-old educator had traveled from the United States to Sudan to celebrate the Islamic holy month of Ramadan with her family when intense battles between the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) broke out in mid-April.

More than 400 people have been killed and thousands more injured so far in the fighting between forces loyal to two generals: RSF leader Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo and SAF chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. The two are former allies but tensions between them arose during negotiations to integrate the RSF into the country’s military as part of plans to restore civilian rule.

While foreign governments are evacuating their diplomats, civilians such as Babikir say they were left behind, enduring rapidly deteriorating conditions and aerial bombardment.

Even as both sides declared a 72-hour truce on Monday for the Muslim holiday of Eid, UN Secretary General António Guterres warned the lack of available evacuation routes could lead to “catastrophic conflagration within Sudan that could engulf the whole region and beyond.”

With few routes out of Sudan, CNN spoke to locals who have made the grueling and dangerous bus journey north seeking safety and refuge, but at the risk of perhaps never seeing their country or family members ever again.

‘Staying was not an option’

“It was a very difficult decision (to leave),” Babikir told CNN. “The biggest factor was that if we stayed it was a death sentence.”

Babikir says she saw pick-up trucks of armed men at Khartoum International Airport, which was shut down after the conflict erupted on April 15.

The closure of one of Sudan’s main transport hubs left many people trapped or scrambling to find alternative exit routes out of the country.

Initially, Babikir says she wanted to gather her loved ones, who all live in the same neighborhood, but nobody could leave their homes for fear of being hit by a stray bullet.

Her family of nearly 30 people was able to congregate in one house, including the elderly, infants and those with underlying health conditions. Their water and electricity supplies were then cut when a pipe was hit by gunfire.

“As soon as we could feel the house shake, and the windows began to shatter in the upper levels, that’s when we knew that staying was not an option,” she says, adding that a neighbor died after her house was ruined.

“Even though taking the road, and the risk we took, was no easy feat… staying was equally unsafe… Our house would have been completely destroyed.”

Khartoum to Aswan

Many Sudanese are making the arduous bus journey to Aswan, a major city in southern Egypt with accessible transport links to the rest of the country.

Muhammad al-Idrisi, an Egyptian tribesman from Aswan who has been helping people fleeing Sudan cross into Egypt, said that people are enduring a 21-hour trek from Khartoum’s Kandahar bus station to the border, traveling over the Arqin crossing toward Karkar bus station in Aswan.

He told CNN that tribal links between people in northern Sudan and southern Egypt mean that tens of thousands of Sudanese people already work and live in the city, making it a favorable destination for those escaping the fighting.

In Sudan, bus drivers are avoiding areas under RSF control, according to al-Idrisi, as they try to avoid skirmishes between the armed forces and the paramilitary group.

Babikir says she saw large amounts of weapons, cars still ablaze, burned buildings and dead bodies while traveling through northern Sudan.

“I think the most terrifying thing of the journey was just thinking about who would bury us if we were to get killed,” she said. “The darkest thought I had was, am I going to get killed in front of my family? Or are they going to get killed in front of me? And if so, who’s going to bury the body?” she said.

“I can’t express how terrible it is to see that the Sudanese people are being left behind… this conflict has nothing to do with civilians,” Babikir continued. “We’re just caught in the middle of two very armed groups of people. Imagine… your special forces and your army going to war against each other in the same country they’re supposed to defend.”

And people are still traveling north to escape the fighting. The number of arrivals from the Sudan “increased by a remarkable percentage” on Monday, al-Idrisi said, adding that transport companies have taken advantage of the situation and raised the prices of tickets to Egypt, which range between 160,000 to 200,000 Sudanese pounds ($280 to $350).

He expects the number of Sudanese people arriving in Egypt to reach 50,000 to 70,000 within a week.

Only women, children and men over the age of 50 have permission to cross into Egyptian territory, al-Idrisi added. Men between ages 18 and 49 must obtain an entry visa in order to set foot in Egypt from Sudan, according to official visa requirements.

“Leaving Sudan is still difficult, particularly in areas controlled by the RSF, but there are quiet areas, making it somewhat safe,” al-Idrisi said.

‘I’m traumatized’

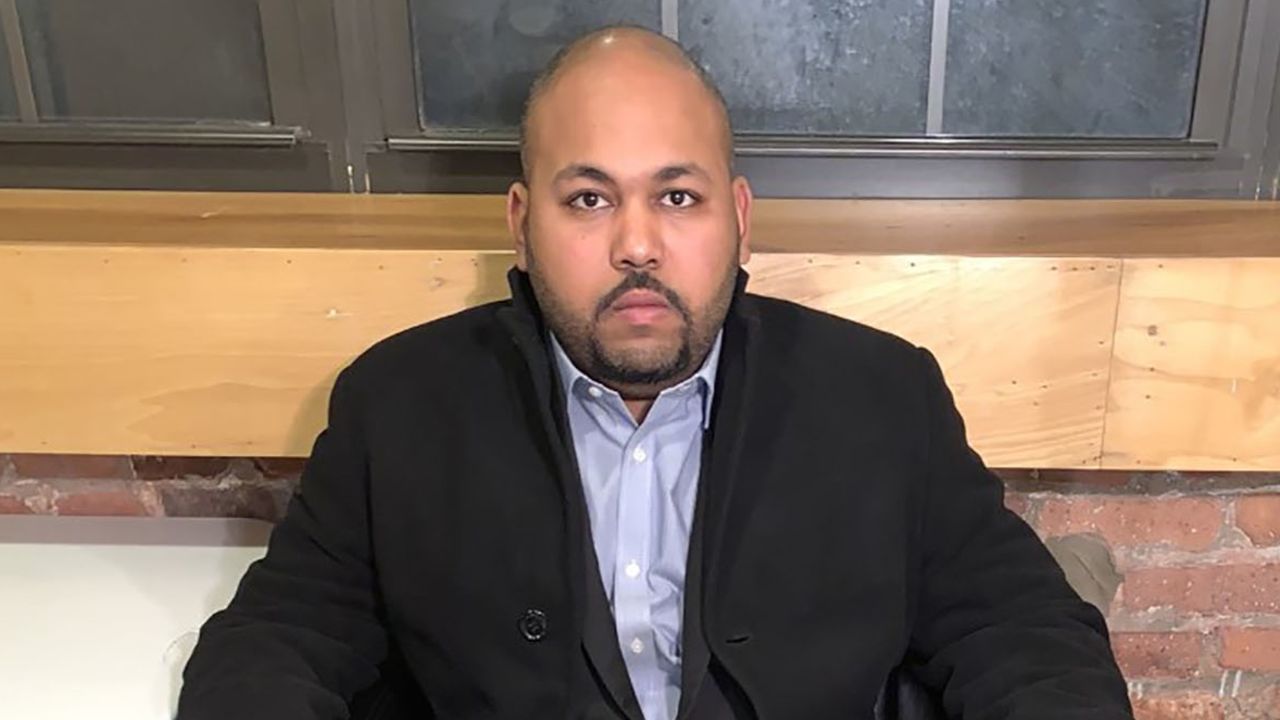

Ahmad Hasan, a 32-year-old international business consultant, says he decided to risk the perilous route because he lived in an area of Khartoum where “the fighting was especially bad.”

Hasan remembers that he was working when he first heard shooting, then decided to stay in the office with some of his colleagues, living off tuna and cheese from local supermarkets. He could hear machine guns and airplanes flying low near his building. Once the group ran out of food, he and his colleagues decided to go their separate ways.

He drove some of them to their homes, then rented a minivan to a bus station and embarked on a three-day journey to Aswan. Even though he found relief when he arrived in Egypt, he is worried for the safety of those stuck in Sudan.

“I feel hand-tied that I cannot really help the people that I know, back home in Sudan, and I don’t know what really is going to happen to them,” he says.

“My eyes are full of tears… I’m traumatized… I honestly cannot see any light or hope… The army and RSF, they have to be forced to stop the war immediately. People are damaged – even healthy people – they will not be able to survive in the next coming days.

“So, it’s a disaster by every meaning that you can actually think of… No one is going to gain anything from the war.”

Imad, a 36-year-old Sudanese man living in the US, said his parents are traveling to Aswan from Khartoum. He last heard from them on Monday after they arrived in the city of Dongula, northern Sudan. It had taken them 14 hours to get there from Omdurman, which lies just outside the capital, a journey that should have taken less than half that.

“Ultimately they were able to escape Khartoum; which seems to be the ultimate mission for a lot of people,” Imad said. “We contacted the consulate in Egypt and they said the border control should cooperate with them.”

“I have never experienced such intensity as I did in the past 24 hours,” Imad added. “The international network of individuals providing vital information, coordinating efforts, and aiding each other in the rescue of their loved ones is unlike any other network I have ever been a part of.” Individuals all over the world are collaborating to find safe routes, arrange transportation, create carpools and link up with embassy evacuation plans, he said.

Babikir and her family eventually made it to the Egyptian capital of Cairo, after staying in a stranger’s house with dozens of other Sudanese people who fled the conflict.

The pain of leaving her uncle behind, as he would not have got a visa, is still raw, however.

“I am relieved that those that traveled with me are alive and that I’m alive, but it is heartbreaking that we may never see our country again and we may never see family members again.”