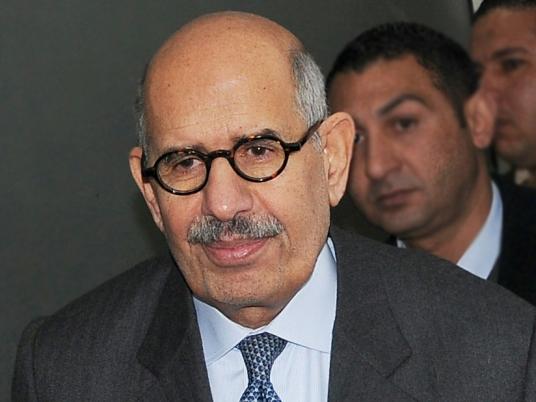

If Mohamed ElBaradei is really planning on challenging President Hosni Mubarak in 2011, he’s pursuing an interesting campaign strategy.

“I don’t want to be president of Egypt,” the former International Atomic Energy Agency chief said, in an interview published last week on the Foreign Policy Magazine website. “You can understand that after having this thankless job for 12 years, that I wanted to have some time to do other things, including spending time with my family.”

Nevertheless ElBaradei-mania appears to be running wild, and should peak later this month when he is supposed to visit Egypt. Supporters of an ElBaradei 2011 candidacy have made their presence felt on Youtube and Facebook—where a pro-ElBaradei group has more than 55,000 members. There’s even an unofficial campaign website.

A collection of opposition activists are already forming a welcoming committee to greet ElBaradei at the airport on 19 February.

"People are desperate to see something new and something true," said George Ishak, one of the founders of the Kefaya movement, who plans to be part of the welcoming committee. "He expresses the desires of the entire opposition. That’s why he has caused such excitement."

The 67-year-old ElBaradei, in a Foreign Policy interview, acknowledged the groundswell of support.

“This issue is coming to me by default; a lot of people are saying that they want me to be engaged in domestic politics,” he said.

It all adds to what should be a fascinating build-up to the 2011 vote. The early enthusiasm attached to a potential ElBaradei candidacy is curious for its sheer intensity– especially since most Egyptians don’t really know much about the man other than his CV. Meanwhile other more well-known figures such as Karama Party leader Hamdeen Sabbahi have already announced their candidacy to much less fanfare.

Columnist and blogger Khaled Diab, writing in the Guardian, speculated that ElBaradei-fever partially stems from the government’s successful campaign to neutralize all other viable options.

“ElBaradei’s popularity is not only a sign of his international standing but also indicates the Egyptian regime’s unofficial policy of engineering the political landscape so that Mubarak appears to be the only show in town,” Diab wrote.

Given the lack of credible choices, it seems likely that a diverse collection of political forces will attempt to rally around ElBaradei as a tent pole for a larger opposition coalition. What remains to be seen is whether ElBaradei will accept that role and whether the people will accept him in that role.

And not all opposition figures necessarily view ElBaradei the same way. Ghad Party chief Ayman Nour said he welcomes ElBaradei’s return and views him as probably qualified to be president. But Nour, who ran against President Hosni Mubarak in 2005, speculated that ElBaradei’s own temperament and desire to remain above the political fray make him more appropriate for a different role. He proposed that ElBaradei be offered the post of interim prime minister, serving through the presidential elections scheduled for next fall.

"That would conform with his own desire not to nominate himself and conform with his desire to remain independent and not join an official party," Nour said.

It will also be worth tracking how the regime responds, especially if ElBaradei continues his criticisms of Egypt’s domestic situation. Last fall, when he first started stirring the Egyptian pot, government-backed columnists dutifully launched a smear campaign. ElBaradei was portrayed as out-of-touch, meddlesome and possibly hiding a foreign citizenship.

Al-Ahram Editor in Chief Osama Soraya famously called ElBaradei "ill-informed," and labeled his entire one-man reform campaign as "tantamount to a constitutional coup."

ElBaradei seemed untroubled by the attacks, and said the government had already abandoned that strategy, which he said only "disgusted" people and enhanced his own stature. "I think they realized they made a terrible mistake because it backfired in their face," he said.

Ishak predicted that the government would shift tactics and make a show of welcoming ElBaradei back home with open arms. "They won’t do [a smear campaign] again," he said. "They tried it once and people thought it was inappropriate and rude."

Nevertheless the fact remains that ElBaradei probably won’t be a candidate in 2011. He has repeatedly stated that he will only run if a highly improbable set of demands are met. These include guarantees of free and fair elections under international supervision and the right to run as an independent candidate. Essentially ElBaradei is demanding that the constitutional amendment passed via national referendum in 2005 be completely torn up and rewritten.

That amendment, which established multi-candidate presidential elections, also came with rules designed to ensure that no independent candidates could crash the party. If he chose to run as a candidate without party affiliations, ElBaradei would have to secure the backing of 250 representatives in both houses of parliament and local councils–all of which are firmly controlled by Mubarak’s ruling National Democratic Party.

ElBaradei has acknowledged that securing his conditions for candidacy will be nearly impossible. Instead he seems to be embracing his role as an outside agitator, using his international stature and profile to pressure the government toward reform.

“I would like to be, at this time, an agent to push Egypt toward a more democratic and transparent regime,” he said. “If I am able to do that, I will be very happy because we need to achieve democracy in the Arab world as fast as we can.”

He already seems to be having an impact. Political analyst and influential Cairo-based blogger Issandr El Amrani speculated about the “ElBaradei Effect” on local politics.

Writing in the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Arab Reform Bulletin, El Amrani stated that ElBaradei’s phantom candidacy has “introduced an unpredictable new element into Egypt’s slow-moving succession crisis. For the first time in recent memory, a prominent member of Egypt’s establishment has spoken out against the Mubarak regime.”

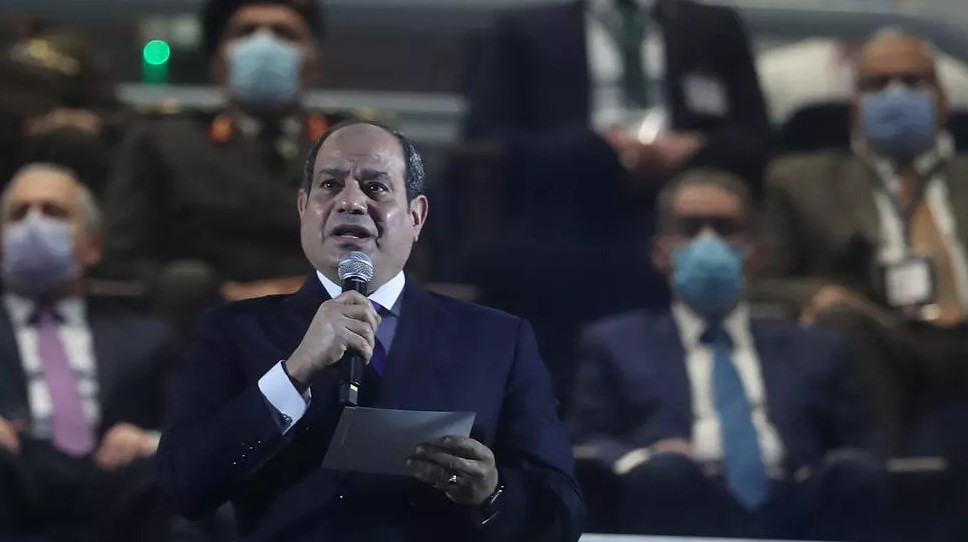

Regardless of whether or not he actually runs, ElBaradei has already positioned himself as a potential complicating factor to long-rumored plans for Mubarak to transfer power to his son Gamal. In opposing that scenario, ElBaradei is building on the foundation established by the Kefaya (Enough) movement—which first captured public attention in 2004 and 2005 by rallying around an anti-Gamal platform.

“Many of these arguments have been made before, but ElBaradei’s stature has given them new moral force,” wrote El Amrani. “His indictment of Egypt’s current predicament is all the more devastating because it comes from a man who appears eminently more qualified for the presidency than the heir apparent, Gamal Mubarak.”