There is no doubt that technology has made our lives easier. From communicating with others despite miles of separation, to shopping with the touch of a button, technology has cut down the time we spend on certain tasks and allowed us to constantly stay connected with others.

However, the ease in which we obtain things or connect with people might be hurting our mental health and creativity. On a larger scale, it might be hurting society as a whole.

If one of the advantages and goals of technological progress is to increase production, create welfare, and achieve the highest possible levels of luxury, then I wonder: To what extent was Abd al-Rahman Ibn Khaldun right in his famous book “Muqaddimah” (Introduction), where he presented the reasons for the weakness and fall of states and the decay of societies?

Ibn Khaldun, a famous Tunisian scholar and historian of the 14th and 15th centuries, created a model for the history of states, which he said had a natural life of birth, maturity and death.

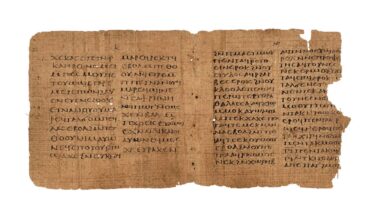

His Muqaddimah, published in Arabic in 1377, written as a prelude to an ambitious survey of global history, asserted that states go through three stages, always ending in failure.

He argued that states, just like humans, go through birth, growth and a fall. There is no escaping this natural cycle, he wrote, and each phase includes certain events and trends that can be identified and described.

Was he right? Well, that may depend on what you call a state. Some countries have been around for centuries and are still going strong. Japan has been an empire since the eighth century and is still headed by an emperor, albeit one shorn of power. France has been a recognized country, with a state, since the fifth century – but its government throughout the past 208 years has been characterized as republican, monarchical and imperial. So, it’s complicated.

However, the model certainly bears serious examination.

The first stage, which Ibn Khaldun calls the ‘establishment phase’, is mostly characterized by zeal: the link that brings together the founding members of the group and unites their forces to establish the foundations of their desired state. For example, the Prophet Mohamed needed zeal to expand the first Muslim state boundaries to the far reaches of Asia and North Africa.

Such enthusiasm, even fanaticism, can be seen at the birth of many states, especially ones born from revolution – as witnessed in the French Revolution from 1789, the Russian revolution in 1917, the American revolution against the British in 1775, and the Iranian revolution in 1978.

These struggles and the energy springing from them underpinned the first stage of the resulting states’ foundations. Their new citizens, comrades and patriots, especially once they gain full rights within a new state, are often the bedrock of its political stability. Their commitment to support their new state and willingness to pay a steep price (even their lives) for its advancement and defense against all threats, gives these new states form and dynamism.

Of course, as these new states settle down, and established order starts to coalesce, a second stage of the state’s life cycle, one of mature stability, means such zealotry is not always welcome. Governing elites start to value economic and scientific progress over blind loyalty to the beliefs that created the state in the first stage. And states may regard such purists as fanatics who need to be tamed.

Trotsky’s grisly assassination by ice pick in 1940 as a political irritant that Stalin could not abide is a case in point. At this stage, said Ibn Khaldun, rulers tend to organize and establish bureaucracies and armies that are run by rules, not emotion. These officials and soldiers need paying for this work, so rulers need to nurture a state’s economy and education to build a sustainably rich society that will support the maturing order.

Such strengths can help a state adapt and attain a ripe old age. The UK, born officially in 1707 with the union of Scotland with England, transformed itself into the world’s largest empire and then back into being a multi-national compact island state.

The British, thus far, seem to have followed Ibn Khaldun’s theories, building up rational support and civic depth, enabling the UK to slow its life cycle and not move to the third stage of decline, weakness and collapse. That said, opponents of Britain’s ‘Brexit’ departure from the European Union (EU), have pointed to risks that this may denude UK financial power and political influence, alongside the loss of Britons’ rights to live and work in Europe. Could Brexit precipitate a long-awaited move of the UK to the historian’s third stage. If Scotland quits the UK over Brexit, to rejoin the EU, maybe it will.

Ibn Khaldun described this stage of weakness as one where citizens lose their enthusiasm for a state, so the forces of coercion – in his time soldiers and officials – grow in significance, but do not generate public support. The economy is then increasingly oriented to the service of law enforcement and political power, losing the state more public support, increasing the political establishment’s reliance on force, in a downward spiral towards despotism.

Citizens then disengage from the state, which becomes vulnerable and open to influence by corrupt external and internal forces, making it less popular than ever. The fall of the USSR is a case in point – between 15 percent and 17 percent of spending went on military services in the early 1980s, leaving the country impoverished and hollowing out support for the communist state. By the time Mikhail Gorbachev took power in 1985 and started reforms, it was too late. By 1991, the USSR was dead.

There are other instances where history follows the Ibn Khaldun model. In Libya, army officers seized power form a king in 1969 and established a state on the foundations of Islam and Arabism. This was developed into an oil-rich state in which Colonel Gaddafi monopolized power. While popular support remained initially, by the end of the last century, it had eroded badly, with Gaddafi increasingly relying on mercenaries to man his army. Patronage and the corruption grew as citizens became less important, and political elites relied on force to stay in power. Eventually a revolt happened, and the Gaddafi regime fell, with a particularly ignominious end for its leader, hauled from a drain and stabbed by a bayonet. Of course, a new sustainable state has yet to be created in Libya. But under Ibn Khaldun’s system, that will come – the next Libyan revolution is coming.

Could this medieval model spell doom for the United States? It certainly does not bode well for American survival. It could be argued that the accession of Donald Trump to the presidency was a sign of weakness. Slogans such as ‘Make America Great Again’ or ‘America First’ bely weakness, showing many American voters fear the USA is no longer a real and strong state but rather a global gathering of people losing its cohesive identity. Does that signal an erosion of civic depth in America, or will the victory of Joe Biden herald the refashioning of the US state as a home for diverse peoples united by the rule of law? Time will tell.

Needless to say, the world today is far more complex than in Ibn Khaldun’s time. And the communications revolution represented by the internet and the spread of knowledge and information, has had contradictory influences. On the one hand, the tendency of social media to corral people sharing the same views on the same platforms has generated extremism because opposing views are rarely heard within organized online groups. But the internet has also created an explosion of accessible information and thought that was not available to even a remote degree before the worldwide web. Even communist China, despite its best efforts cannot wall off the world from differing opinions.

Will the internet undermine or strengthen the validity of Khaldun’s model? Maybe neither – it might just speed everything up. The self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in his native Tunisia during 2010 sparked internet-fuelled protests that ultimately felled a despot in the country and ushered in a new democratic state. Web services also encouraged right wing protestors to invade the US Capitol this month, highlighting the weaknesses and divisions of the US political system.

Furthermore, if we all live to pursue mass production, the easing of life, and the luxury of abundance, then the saying “knowledge for the sake of knowledge” regardless of any moral, ethical or teleological restrictions or conditions poses a concern. Will Ibn Khaldun’s prophecy be realized due to the reactionary effect of welfare and luxury?

Ibn Khaldun’s vision is supported by Alain Deneault’s position in his book “Mediocracy” in which he describes the current time as a unique stage in human history. However, this stance he takes is not a positive one.

Denault asserts that currently, “mediocre” control prevails in the world and has its grip on all aspects of society, spreading “mediocracy” via technological, economic and digital progress.

Might this lead to destruction that Ibn Khaldun warned us of centuries ago? Or is this merely the next stage of civilization that will bring about the benefits we need to make the world a better place?

_____________________

Hasan Abdullah Ismaik is the Chairman of the investment company Marya Group, a global multi-billion dollar investment headquartered in Abu Dhabi, the capital of the UAE. In 2018, Ismaik launched the STRATEGIECS Think Tank, a research center specialized in qualitative strategic studies related to political, economic, social, and demographic transformations in the Middle East. For more than twenty years, he has been dedicated to presenting his views via published op-eds on security, peace, and the future of stability in the Middle East and the world.

This is the second part of a two-part article. The first part is available here.