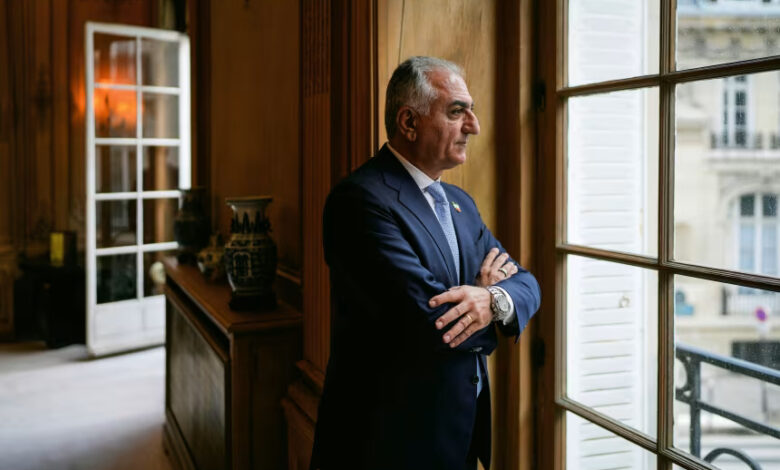

Reza Pahlavi was only 16 years old when Iran’s 1979 revolution toppled his father’s 40-year rule. The eldest son of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, he was the first in the line to inherit the oil-rich thousand-year-old empire.

Now at the age of 65, nearly half a century after the unravelling of his birthright, his wait may finally be coming to an end.

“This is the last battle. Pahlavi will return!” was one of the standout chants from nationwide protests that gripped Iran on Thursday night after the exiled former crown prince exhorted his compatriots to hit the streets.

“Javid Shah (long live the king)!” cried the protesters. “Reza Shah, God bless your soul!”

Thursday’s protests were the culmination of days of demonstrations that began in Tehran’s Grand Bazaar against economic grievances but have quickly taken on an anti-regime focus. Pahlavi, who is based in the US, has sought to position himself as a de facto leader.

Support for the deposed monarchy is taboo in Iran, a criminal offense, and a sentiment long frowned upon by a society that staged a popular uprising to overthrow the Shah’s dictatorship.

It is unclear what might be driving the renewed excitement for the royal family and its titular head in exile, analysts say. Do Iranians genuinely support the restoration of the monarchy or are they just fed up with their repressive theocracy?

“Reza Pahlavi has indubitably increased his clout and has turned himself into a frontrunner in Iranian opposition politics,” said Arash Azizi, an academic and author of the book “What Iranians Want.”

“But he also suffers from many problems. He is a divisive figure and not a unifying one.”

For decades, the Islamic Republic has neutered its domestic opposition, imprisoning its critics including former presidents. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the ultimate authority in Iran, circumscribes the powers of elected officials and views his mandate as the guardian of the regime, stamping out challenges to its rule.

This has empowered the external opposition, growing out of Iran’s large diaspora and pulling figures such as Pahlavi out of relative obscurity. Pahlavi first burst into the spotlight after Iran in 2020 accidentally shot down a commercial flight after it took off from Tehran bound for Ukraine. The incident galvanized the external opposition prompting them to coalesce into a council that had Pahlavi as a prominent member.

Disagreements between the patchwork of Iranian dissidents led to the council’s early demise. But Pahlavi endured as the most well-known face of the opposition. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has been his most high-profile backer. It’s an alliance that has polarized Iranians (Israeli strikes pummeled parts of Iran during a 12-day war between the two countries last June).

US President Donald Trump’s abduction of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro also may have energized an opposition hoping for a quick decapitation of the regime. Social media footage showed a protester changing a street name to “Trump Street.”

But analysts say those hopes may have been misplaced. Trump “is weighing his options and has no desire to lend credibility to someone before they’ve proved they can win,” said Azizi.

“Pahlavi personally doesn’t have qualities that appeal to Trump. He is rather bookish and lacks the kind of personal charisma that could appeal to someone like Trump,” said Azizi. “He will have a hard time winning over Trump.”

Pahlavi has been non-committal about stepping into the fray. He has said he is willing to lead Iran in a transition in case protesters succeed in ousting the regime in these demonstrations, the fifth anti-regime protests in nearly a decade. But he is sparse on the details of his plans and his critics say his inexperience may soon turn against him.

“He talks of being a transitional leader and having a transitional assembly, but who is going to be in the transitional government, who is going to run in the assembly, who are your candidates,” said Vali Nasr, an Iran expert and professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies.

“It’s one thing to look at crowds and say it would be great if Iran goes back to the Shah’s period but in terms of real mechanisms, how would he do that?”

The rallying around Pahlavi is the surest sign, analysts say, that Iran’s Islamic Republic appears to have hit a dead-end. Its economy has buckled under years of corruption and sanctions, and it has struggled to shake off its pariah status despite the efforts of a slew of reformist governments. Young people have chafed under conservative rule and the stifling of political freedoms. And if the regime tries to violently quash the uprising, as it has done previously, then it risks drawing Trump’s wrath.

“Iranians aren’t opting for (Pahlavi) because he is present in the community but because they are despondent,” said Nasr.

Pahlavi capitalizes on that nostalgia for a pre-Islamic Republic era. “Many older Iranians remember the day I was born and what a national frenzy there was,” he told The Wall Street Journal this week. “But now at the age of 65 … the young Iranians call me father. And that’s the best thing.”