LONDON — When Tarek and Amal do food deliveries, they get glimpses into the homes of the wealthy. Sometimes the door is closed abruptly as the customer or Filipina domestic worker goes to find money, or the door is left open allowing them to stare at opulence.

Tarek and Amal are the couple at the heart of “Cairo Exit.” Tarek is Muslim and Amal Christian. This relationship across religious — and therefore social — boundaries could be seen to be the crux of the film. When director Hesham Issawi has spoken in interviews and events, he has repeatedly recounted how “Cairo Exit” had to be filmed guerilla-style because of the censors.

And the reason for the censorship was the love story between a Christian and a Muslim. Indeed, this emphasis on the religious aspect of the film is reflected in the fact that at the London MENA Film Festival at the end of October, “Cairo Exit” was screened alongside “Jesus, Mary, Allah and the others,” a documentary following a multi-faith band in post-Mubarak Egypt.

But if the film has to be about something — and it is in a sense a social drama — then it is less about star-crossed love than the absence of social justice. It is not that they are of different religions that constrains them and their relationship as much as it is their poverty.

However hard they work, it is never enough. Tarek is fed up and has decided to leave Egypt. The escape —or exit — does not entail visas and paperwork. It entails risk, layered with more risk, as he saves up the money to pay the smugglers who will get him, with Amal he hopes, on a boat to Europe. Interestingly, in Arabic the film is simply called “The Exit,” while the English title makes Cairo explicit.

Amal’s choice is a stark one. Either she goes with Tarek or stays and loses him. She asks him to stay. He will not. One day, after they argue about this, she tells him she is pregnant. Theirs is a difficult relationship, but it is beautiful. The way they dance together on a roof one day, the way they laugh easily even when they have been fighting, attest to how their love provides them both with warmth and solace. At the end of her difficult days at work, after she gives money to her mother, she lies in bed, finally smiling as she thinks about him.

Tarek and Amal’s relationship is at the center of “Cairo Exit,” but it is Amal who is the film’s anchor. Tarek has decided to go. There is no dissuading him. We watch her struggle, her sense of obligation toward her mother pulling against her fear of losing Tarek. She has a depth that we do not see in the other characters.

It is through Amal that we meet most of these other characters, all looking for ways out of their predicaments. Her mother, widowed, married to an unstable gambler and unable to control her grandson. The mother of the grandson, Amal’s sister, rarely around. Later, when Amal is on a visit working for a hairdresser, she finds herself in a brothel and face to face with her sister. Her good friend Rania is entering into a sham marriage with a wealthier man, both to get away and to get enough money for an operation to restore her hymen.

It is somewhat cliché to describe a film like “Cairo Exit” as raw and gritty. These terms do not really capture the film, but it is certainly uncompromising. The issues which the threads of the plot tie in are multiple.

Though in places we can predict what will happen, in more fundamental ways, the film is far from predictable. We do not know what decisions the characters will make, nor what bad luck will befall them — though we know there will be bad luck. And, the key driving question of the plot, we do not know the answer to: will Amal join Tarek in leaving Egypt and taking the dangerous journey across the sea?

Co-written with Amal Afify, “Cairo Exit” is director Issawi’s second feature. It was finished just months before the uprising, and premiered at the end of 2010 at the Dubai International Film Festival.

It is beautifully filmed — the use of naturalistic lighting, the soundtrack and the camera create a sensitive gaze. It has the aesthetics of a film, with the plot and acting of a soap opera. Crucially, apart from the protagonists, the acting is melodramatic. Some people may like this; the consistently high viewership of soaps show there is certainly an audience for it. But it detracts from the film’s intensity.

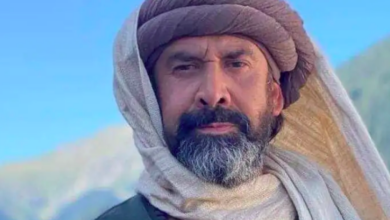

While most of the acting is melodramatic, the acting of the protagonists is of a different mold. Maryhan in the role of Amal is impressive; she has both depth and variety, maturity and girlishness. In comparison, Mohamed Ramadan, playing Tarek, is somewhat wooden, but this is his character. While Amal is more transparently loving, Tarek is often gruff. More than anything he expresses his love simply by always being there for Amal. Anything she asks, he does it. Any time she needs him, he drops everything for her. He is her rock in a harsh and unforgiving world.

The film humanizes its characters. And its humanity lies not in the way it asks us to sympathize with them. Rather, it is in the way they are doing the best they can in situations where they are pushed to their limits.

There is no moralizing in relation to Amal’s sister working in a brothel. An audience who might be inclined to condemn her is compelled to think twice. It is in the confrontation between the two sisters that the film is most explicit in its social messaging. Amal judges her sister, who defends herself, pulling apart the idea that marriage is a line of morality. Isn’t Rania also selling herself, she asks. She is doing the only job she could find that meant she could provide and save money for her son. “He’ll live like a human being. If the price is that I sell myself then I don’t mind,” she says to her sister. “If I could sell part of my body, I would.”

“Look around,” she says, “everyone is selling themselves.”

And while Amal is harsh in her judgment, you get a sense that she is harsh only because she knows her sister is right. One day she comes home to find her nephew begging, she grabs him by the ear, marching him home, bemoaning his lack of self-respect. When she gets a job at the hairdresser where Rania worked, Amal bites her lip as the owner of the salon, the archetypal mean, rich boss, is openly rude and disrespectful. She tells another of the employees to instruct Amal in her work, and Amal does indeed start imitating her. She takes on a moaning, whining tone, telling the women whose legs she is waxing and feet pedicuring about her sick husband and four children. She knows she is also begging.

The question of dignity is a recurring one. In a rare scene of tenderness between Tarek and his otherwise harsh and critical brother, his brother tries to convince him to stay, even if he does marry his Christian girlfriend. “What’s wrong with this work?” he says painting the walls of a flat. “Why go drown yourself.” But Tarek is determined. “There is nothing dignified here.”

“Life there wouldn’t be easy,” he says, “but you would have dignity.”