For over 40 years Egypt’s premier French research center has been been housed in the heart of downtown Cairo. The Centre d’Etudes et de Documentation Economiques, Juridiques et Sociales (CEDEJ) has been a hub of dynamic academic activity since 1968, but by the beginning of 2010 things will change dramatically for the center.

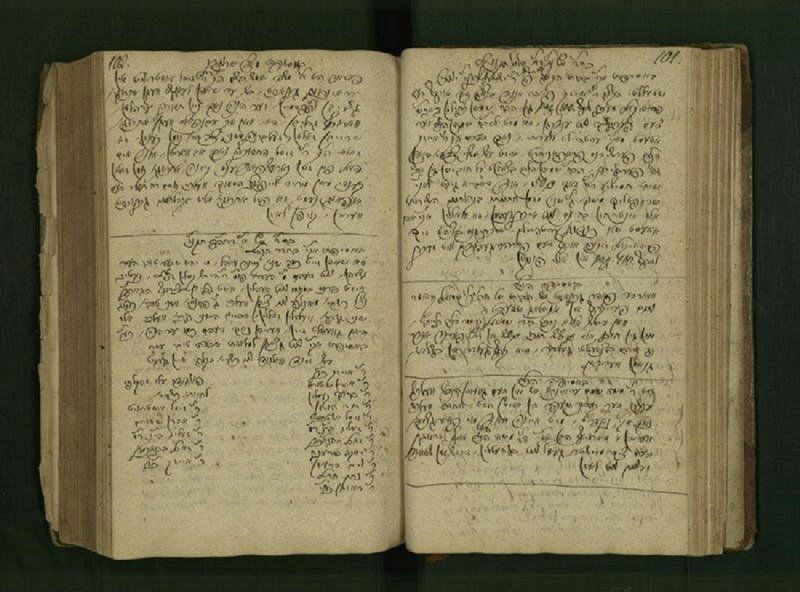

The CEDEJ will relocate its premises by next year, but perhaps more DRAMATIC for scholars will be the closure of its library, which is home to no less than 48,000 books, two thirds of which are in Arabic, as well as the collection from the French School of Law, and a press archive dating back to 1976 and indexed by 1200 issues. The closure will also entail firing seven employees who have worked at the library for years.

The CEDEJ’s leadership has a new vision for the center, but it’s not one that always appeals to researchers. “We need to modernize our tools,” says Marc Lavergne, head of the CEDEJ, who believes that the CEDEJ can play a central role in international understanding, particularly regarding controversies like the Swiss minaret ban and niqab in France. “The CEDEJ will fall very short if measures are not taken right away.”

Current research themes in the CEDEJ include waste management, pollution, Cairo’s urban development, the future of the Muslim Brotherhood, Internet laws, workers’ movement, women’s issues, globalization and patriarchy.

Modernization starts with the library, according to Lavergne. “The press archive is particularly specific to CEDEJ, because it involves the thematic classification of media clips. But this process is becoming incomplete and obsolete. On one hand, it’s expensive to hire staff to do this process. On the other hand, there is information that comes through other means than print media.”

That the archive can only be accessed on the premises of the CEDEJ makes it impractical, according to Lavergne. “We have to rethink all that. We have to find alternative methods with young intelligent people who are university graduates. Some of the current employees are not.”

On 14 December, employees working in the library of the CEDEJ were told that their term had come to an end. French ambassador to Egypt Jean Félix-Paganon told employees that the library will be closed altogether and that the center may be transferred to Alexandria, where it could engage more in Euro-Mediterranean projects.

According to the Egyptian Center for Economic and Social Rights, negotiations were arranged on 21 December between the seven employees, lawyers, and representatives of the CEDEJ and the French embassy. After the meeting, the employees were granted some financial compensations and a three-month notice. But certain issues are still pending, such as the exact value of the severance package and the question of arbitrary disbanding, which CEDEJ originally wanted to make a two-month salary for each year of service.

“Since the last meeting, the staff and their representatives are formulating their demands. I have little hope that our voice will be heard and that our colleagues will manage to have a better departure,” says Iman Farag, a sociologist who worked with the CEDEJ for 20 year and today represents its employees.

Academics, researchers, and former managers at CEDEJ have written petitions to the French ambassador in Cairo over the closure of the library.

“Shuttering any kind of library in Egypt is a real loss… In the spirit of knowledge building that CEDEJ has embodied for so many years, we strongly urge you to reconsider the decision and keep the library doors open. Generations of past and future researchers will be grateful,” reads one of the petitions.

But according to Lavergne, the library’s closure will only be temporary since the French Embassy will sell the CEDEJ building, along with the consulate. While the consulate will move to the embassy premises in Giza, CEDEJ has the option of relocating to the premises of the French consulate in Alexandria or renting a new space in Cairo.

“So far, CEDEJ does not have the money for rent. We’ve been hosted by the embassy for free,” says Lavergne. Finding a proper space is a challenging task with the library acquiring as many as 1200 titles every year and 5000 un-indexed books in storage. “Where to put all this? We are strangled and we have to find a proper space.”

Most of the CEDEJ’s funding comes from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. This mainly covers salaries. “This funding has been decreasing year after year, as has been the case with all French cultural and scientific establishments abroad. The financial crisis is not a secret,” says Lavergne. “We only survived through the reduction of our researchers. A research center without researchers is impossible.” Much of the current research at CEDEJ is funded through external partners.

The closure of the library and relocation of the CEDEJ are seen as part of a larger political and cultural policy shift. Malak Labib, a former intern with the CEDEJ and current PhD candidate in history in the Institut de Recherches et d’Etudes sur le Monde Arabe et Musulman, expressed her disappointment. “It’s very sad that the French Foreign Ministry is opting to stop spending on research in Egypt and the Middle East in general. It’s a disaster to transform the CEDEJ into a practical, business-oriented establishment.”

The possible relocation of the CEDEJ to Alexandria, with the aim of transforming it into a hub for Euro-Mediterranean research, is similarly problematic for many. “Is it normal to impose a research axis on a research institution as part of a political agenda? Can an establishment reduce its means and increase its field of activities at the same time?” reads the statement of one group of petitioners.

Lavergne maintains that he is fighting for the CEDEJ’s survival, and is accordingly planning for its re-conception. “I understand the nostalgia to the CEDEJ of the 1980s and 1990s, but Egypt is changing and many people do not know the CEDEJ. I am interested in those people.”