With a knife between his teeth, Salah Mahrous leaps down from the wall, an Amr Moussa banner trailing behind him. “The elections are over,” the frowning 19-year-old says, even though the polls aren’t set to close for several hours. “Happy New Year.”

Despite his repeated insistence that “nobody can open their mouths [to object],” he doesn’t waste time bundling the length of vinyl in his arms as his younger brother, Ahmed, keeps a casual lookout. The two rush off, heading down Dar al-Salam’s Ateya Beleila Street, and joking between themselves.

For the brothers, taking Moussa down isn’t a political, or even personal, issue. It’s just business. They know that after the election those thousands of banners costing millions of pounds will be ripped down and tossed out. To them, that doesn’t make much sense.

“I’m going to sell it,” he says of his newly acquired propaganda. “For LE50, maybe LE100.”

Mahrous estimates the banner cost more than LE100 to make, but to him that’s irrelevant. “What did it cost, a thousand? Nobody’s going to pay me that for it. Especially when it has this chump’s face on it.”

It’s a coincidence, Salah insists, that he neither supports, nor respects Moussa. “I voted for [Abdel Moneim] Abouel Fotouh,” he shrugs. “But I’ve sold him as well.” At the rate the brothers have been capitalizing on images of the next president, it’s more of a lucrative hobby than an actual business; they are making the most of a short-lived opportunity.

“I sold a banner for LE50 to a fruit vendor the other day; he used it to protect his stand from the dust storms,” Mahrous recalls. “It was [Muslim Brotherhood candidate Mohamed] Morsy. The fruit vendor asked me if I had anybody else.”

Besides disillusioned fruit vendors and other assorted stand owners, Salah asserts that there is a market for his banners, and a desperate one at that.

“This is the perfect material for a roof,” he says. “It’s waterproof and keeps the sun out. A lot of people need something like this to lie over the holes in their roofs.”

The thought of a candidate’s face physically shielding the otherwise roofless from rainy days and dust storms seems ironic only because, as Salah puts it, “It’s likely the one thing most of these men will ever do for us.”

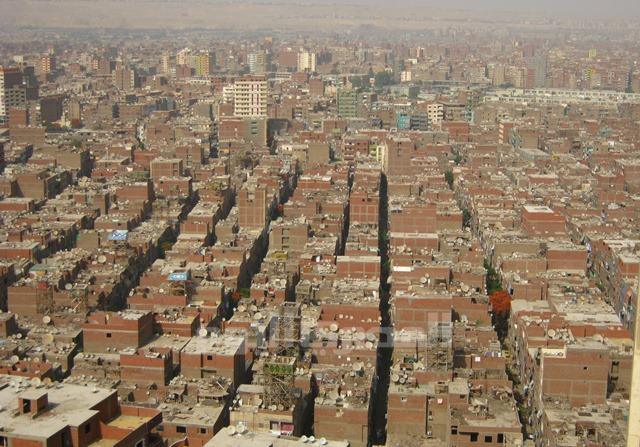

“Us” being residents of areas like Dar al-Salam, where the Mahrous boys were born and raised. It’s a district that Salah claims has never been on the former president’s map — although his police forces seemed to have no trouble finding it.

Even after the uprising, lifelong resident Hassan Yemeni remains resentful of the fact that “people say Dar al-Salam is full of thugs, when they only learned thuggery from the former regime, and the way it used to force them to live.

“This is damage that can’t just be erased with a new president,” the computer engineer says on the first day of voting. “Whoever wins these elections will have to make up for the former regime’s sins, starting with low-income neighborhoods and rebuilding the people’s faith in the police force.”

Mohamed Fadl, a 24-year-old resident of Dar al-Salam and volunteer on a presidential candidate’s campaign — he asked it remain anonymous — is familiar with the Mahrous brothers’ brand of entrepreneurship, having personally witnessed, and then contributed to it. He recalls a late night some weeks prior, when he and a group of volunteers were pasting their candidate’s posters down Haram Street. “We kept seeing this group of five or six kids — really young children — climbing lampposts, loosening banners and running off with them.”

When Fadl finally caught up with them, the children explained they were gathering the banners to use as blankets. “So we helped them bring a few more down,” Fadl says with a smile. “Win-win.”

This in a way also describes how Ahmed Radwan, better known as Hajj Bilal, views the election. In the same week — sometimes in the same plastic bag — the grocer has distributed promotional material for different candidates.

“My brother brought these,” he points to a thin stack of leaflets bearing images of scholars and football players who endorse Morsy, “and someone dropped these off,” he pulls a brick of Mohamed Selim al-Awa fliers out from under his counter. “I swear, for the first day I didn’t even notice they were different.” Not that that would have affected his opinion. “I keep saying let them all win. People want unity? Let them all win. And then each one of them can pick a problem to focus on and fix.”

Given his ideal solution, the 63-year-old has understandable differences narrowing his choice, so much that, four hours before polls are set to close for good, he has yet to cast his vote. “I’ll go, don’t worry,” he says, grinning. “I just haven’t made up my mind yet.”

Across the street, in a tiny restaurant named Feed Me, Thank You, Khaled Abu Steit explains why he’s been more decisive than the grocer. “He’s an older man who hasn’t seen anything good come out of politics in a long time,” the 26-year-old says. “But I knew who I was voting for a while back, and so did most of my friends and family. Unfortunately, we’re not all for the same candidate, even though we all want the same basic things.

“People in neighborhoods like this, we have the most to gain from these elections but only if they bring a president who introduces real change,” Abu Steit says. For this he placed his faith in Abouel Fotouh, stating his belief that “he shares all the other candidate’s strengths and none of their weaknesses.”

Despite what Abu Steit says, though, it’s not just Dar al-Salam’s older residents who have a hard time believing real change will ever come. In fact, one of his own closest friends, Sherif Ali Youssef, 27, remains undecided a few hours before the closing of the polls, admitting that he’s “likely to boycott.”

“Look,” Youssef says. “I don’t care who’s Islamist and who’s feloul. All I care is that of all those educated Muslim candidates, none saw fit to donate some of their campaign funds to the people whose votes they depend on, instead of spending all those millions on printing pictures of themselves. If a single candidate had stepped forward and provided shelter to a family in need, or even renovated a public park or cleaned up a neighborhood like this, I would have been the first in line to vote for them, be they man, woman, Copt, cat, dog, anything.”

When Abu Steit points out to Youssef that much of the promotional material has been either donated, or paid for by the donations of independent campaign supporters, Youssef frowns. “That’s even worse. We want a president who rights wrongs, and sets a good example,” he says.

“We’re already off to a bad start.”