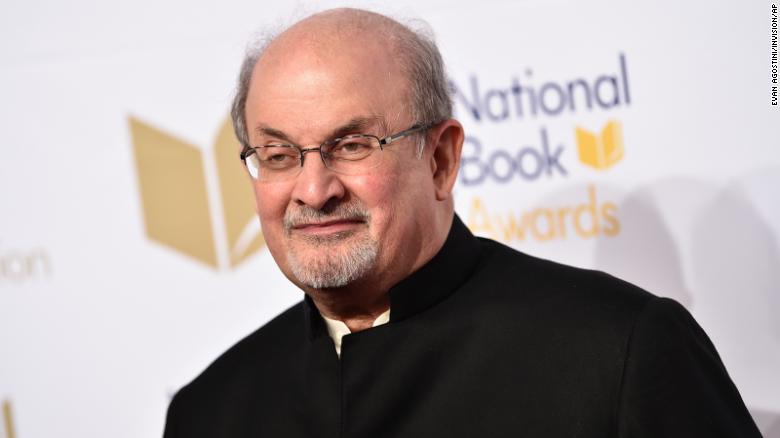

(CNN) – Nearly 10 years after he was driven underground, Salman Rushdie believed he was free. The author had been living under heavy security and highest secrecy in London. But in 1998, the Iranian government of President Mohammad Khatami publicly distanced itself from the religious fatwa calling for his murder.

The move was part of a landmark agreement with the United Kingdom. Iran issued a public guarantee not to push for Rushdie’s murder in exchange for an upgrade in diplomatic relations between London and Tehran.

“Well, it looks like it’s over,” Rushdie told reporters at the time. “It means everything. It means freedom.”

But there was a catch. The murderous 1989 decree over Rushdie’s satirical novel The Satanic Verses could not be officially revoked because the source of the fatwa — Iran’s first Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini — was dead. At least that’s what Rushdie was told, according to his memoir.

It was a deftly-crafted ambiguity that has defined Iran’s policy over the issue — and many other issues — in the intervening years. In 2006, Hassan Nasrallah, secretary general of Iran-backed Hezbollah, publicly lamented that the fatwa against the author had not been carried out, claiming it emboldened others to “insult” the Prophet Mohammed. In 2019, Iran’s current Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei reminded his followers that the ruling against Rushdie was “solid and irrevocable,” in a tweet that led to the shutting down of his account. Khamenei still tweets from other accounts.

Four months before Rushdie was brutally stabbed at an event in New York on Friday, an Iranian news outlet, Iran Online, published an article praising the fatwa.

Throughout it all, Iran appeared to insist on continuing to dangle the executioner’s sword in front of Rushdie.

Regardless of their motivations, Iran’s cynical exploitation of some Muslims sensibilities is plain to see. The Satanic Verses draws on a deeply controversial story in early Islamic tradition that claims that Satan momentarily intruded in the divine revelations to the Prophet Mohammed. Iran didn’t ban the book straightaway; the country’s rulers only took action several months later, after the book inspired protests in Pakistan.

The ensuing fatwa proved to be politically useful. It elevated Khomeini in the eyes of Islam’s fundamentalists across the Muslim world, including among Sunnis. Yet then, as now, it had its prominent Muslim and regional detractors.

The New Yorker’s Robin Wright reports that Khomeini’s closest protege at the time, Ayatollah Ali Montazeri, criticized the decree. Montazeri, who also opposed mass executions of Iran’s dissidents, fell out of favor with the regime and was placed under house arrest in 1997.

A 1989 letter published in The New York Review of Books signed by Arab and Muslim scholars also decried the campaign against Rushdie.

“This campaign is done in the name of Islam, although none of it does Islam any credit,” the letter signed by five prominent intellectuals including the late Indian-born poet Aga Shahid Ali and the late Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said.

“Certainly Muslims and others are entitled to protest against The Satanic Verses if they feel the novel offends their religion and cultural sensibilities,” the authors of the letter added. “But to carry protest and debate over into the realm of bigoted violence is in fact antithetical to Islamic traditions of learning and tolerance.”

In Rushdie’s memoir Joseph Anton, the Mumbai-born author is depicted openly questioning whether he was being “sold out” by the London-Tehran 1998 agreement only days after he declared the threats to his life “over.” Joseph Anton was his pseudonym during his time underground and he refers to himself in the book in the third person.

Despite acknowledging that the death warrant would continue to hang over his head, he opted to emerge from his life in hiding and settle in New York where decades later, he would be brutally attacked in front of horrified onlookers.

The suspect in last week’s attack was named by authorities as Hadi Matar, a 24-year-old from New Jersey.

Matar pleaded not guilty Saturday to attempted murder in the second degree and other charges.

True to form, Iran denied involvement in the attack and said Rushdie and his “supporters” had only themselves to blame. Hezbollah also said they had no information about the attacker and the plot in comments to CNN.

“Nothing was ever perfect, but there was a level of imperfection that was hard to take,” Rushdie wrote in his memoir of the 1998 decision. “Still, he remained resolved,” Rushdie added, referring to himself. “He had to take his life back into his own hands. He couldn’t wait any longer for the ‘imperfection factor’ to drop to a more acceptable level.”