The public outrage over the killing of Cecil, the Zimbabwean lion, followed by the online attacks on American hunter Sabrina Corgatelli's killing of a giraffe, has brought the fragility of our planet's wildlife to the forefront and shown the strong role social media has the potential to play in conservation.

Modern day technology can now facilitate individual efforts, which by themselves might not amount to much, but as a collective movement can make a difference.

Conservation efforts have evolved over the past 150 years to embrace new ways of approaching the environment and wildlife. Organizations have made great strides in involving individuals and communities to assist in protecting plant and animal life through the use of social media and other technological advances.

National Geographic published an online article earlier this year specifying different technologies people are using to help identify, track or research wildlife. This type of crowd sourcing, or crowd science as some call it, is helping scientists and conservationists cull information at rates they were never able to reach in the past.

Protecting endangered species: There’s an app for that

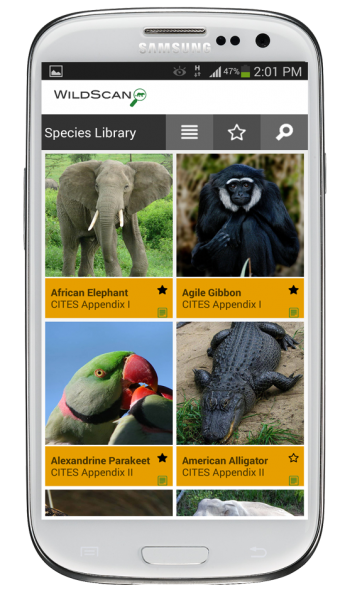

Screen capture of the WildScan app's species library section. Photo courtesy of Freeland/Matthew Pritchett

One way to crowd-source conservation is through mobile phone applications. The WildScan app, launched by Bangkok-based NGO Freeland in September 2014, consists of a catalogue of over 340 endangered species that both governments and individuals can use to identify the trafficking of wildlife, both in country and abroad.

Freeland, a self-described frontline counter-trafficking organization, has made the app available for free from Google Play on Android devices.

The organization worked closely with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ Wildlife Enforcement Network (ASEAN-WEN) and many other organizations to create the app. ASEAN-WEN is the biggest wildlife law enforcement network in the world and consists of 10 Southeast Asian countries dedicated to sharing information and using their resources to combat wildlife trafficking.

WildScan has, to date, been downloaded in over 20 countries worldwide, from Thailand, Vietnam and the United States, to France and Denmark. The app currently operates in English, Thai and Vietnamese. Three to four new languages will be added by the end of 2015 and further global expansion is expected in 2016. The purpose of the app is for people to be able to identify and report wildlife trafficking incidents worldwide.

Though WildScan was developed in Thailand, it is not, as some would assume, only referencing wildlife from that region. Egypt Independent spoke with Matthew Pritchett, Deputy Director of Communications for Freeland and Project Manager for WildScan.

“We looked at animals that are trafficked through Southeast Asia, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that they come from here,” said Pritchett.

A Hamilton’s turtle, which was one of more than 400 stuffed into a suitcase on board a plane headed for Southeast Asia. Photo courtesy of Freeland/Matthew Pritchett

“Don’t get me wrong, animals that originate from Southeast Asia, like the slow loris, gibbons, pythons, sea turtles, definitely those are in the app, but we also looked at animals say from South America, like parrots for the bird trade, or animals from Madagascar, like tortoises. Those are also trafficked through Southeast Asia, especially in big cities like Bangkok so those species and those species’ products, like elephant ivory, are incorporated in the app as well.”

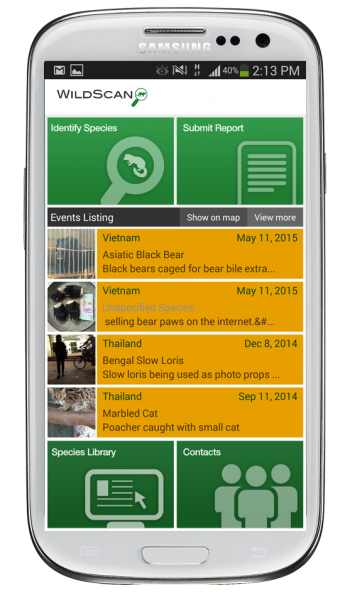

The WildScan app is divided into five sections consisting of the species library, the contacts directory, the identify species section, the event listing section and the submit report section. Both individuals and government officials can use it to help identify species they are unfamiliar with, look through the catalogue of species to see which plants and animals are protected or endangered, contact local officials to report trafficking incidents and even load a report on an illegal citing, whether in a local marketplace or in rural areas.

WildScan app. Photo courtesy of Freeland/Matthew Pritchett

Since its launch in September, WildScan has been downloaded over 700 times, both by individuals and law enforcement in several countries. Though the number may seem small to some, given the fact that many of the downloads have been made by wildlife officials who were attending workshops and are few in number, Freeland is encouraged by the response. The next step is to stimulate more individuals to help stop wildlife trafficking by downloading the app and reporting incidents they may be privy to.

Although statistics on the success of the app in helping with conservation efforts are not readily available, as the information belongs to individual governments, Freeland has nonetheless gotten some feedback from users.

“I do know one case in Thailand where there was a Thai ranger who phoned us up and said that he was able to use it to identify an orchid that somebody had just taken out of the forest, which did lead to the man’s arrest,” said Pritchett.

Despite the fact that the app was initially built for the ASEAN-WEN country governments in order to help support and empower wildlife-trafficking law enforcement officers in the region, Pritchett is clear on the bigger picture.

“I think it’s important for us to point out that WildScan is not a tool that is only available to law enforcement. It is an education tool. We do use it at schools, we take it to show kids. It’s an easy way for you to look at which animals are protected and threatened from trade. If you wanted to go buy an exotic pet at a pet store, WildScan would be able to show you the animals that you shouldn’t be buying.

“Even more than that, the public can use it for free and they can actually send in reports that will go right to the proper police station or wherever it needs to go. It’s pretty neat that the general public has access to the same tool as law enforcement to stop wildlife trafficking.”

A slow loris rescued in SE Asia from the pet trade. The small primates are becoming increasingly popular in Europe and Russia and their demand is fueling the illegal pet trade. Photo courtesy of Freeland/Matthew Pritchett

Conservation starts as top-down approach

The WildScan app seems to signal a gradual change in tactics for the conservation movement, which has not always been so open and inclusive to the community it affects, but rather run on decisions made by a select few with authority in the movement.

The origins of nature conservation date back to as early as 1662 when English writer John Evelyn submitted “Sylva, or A Discourse of Forest-Trees and the Propagation of Timber in His Majesty's Dominions” to the Royal Society in England. In it, Evelyn discussed the importance of conserving English forests, which were at that time being quickly depleted in favor of the timber industry.

The types of environmental organizations that are currently most familiar, however, such as Greenpeace, the National Audubon Society, the World Wildlife Fund and the National Geographic Society, were established between the late 1800s and the mid-1900s when conservation efforts began to intensify.

For decades prior to the technological advances the planet has undergone, governments and environmental organizations managed conservation efforts by focusing predominantly on saving the environment. The impact on local communities, unfortunately, was often overlooked in the process.

Illegal ivory discovered hidden in suitcases. Photo courtesy of Freeland/Matthew Pritchett

Governments and NGOs would traditionally adopt a top-down approach wherein they would study an area, determine what the problem was and attempt to solve it without actively involving the local communities. That meant that organizations would go into the area in question and inform communities about new laws. Fines or prison terms were then imposed and people would suffer the consequences if caught killing, poaching or smuggling wildlife.

This approach to conservation often ignored the motivations communities had for wildlife killing and trafficking. Some animals are deemed a pest, such as the snow leopard in Northern India which hunts and kills farm animals. Other animals may fulfill a black market demand often connected with traditional medicinal practices, like the Nepalese one-horned rhinoceros, whose horn is believed to heal certain ailments. Rare plants, such as exotic orchids, are also common trafficking goods that can be sold to collectors for personal enjoyment or to nurseries for cloning.

Since the possibility of earning a better living is a great motivator, many people have continued to risk fines or imprisonment in favor of supporting their families. As a result, an increasing number of organizations have realized that in order to truly protect fauna and flora from extinction, there must be a cohesive and integrated approach to conservation.

Conservation today

In the present day, hundreds of NGOs, as well as government entities, are making efforts to change the way in which they approach conservation. Rather than simply inform people of changes and restrictions, local communities are now being asked what the issues are and are being included in the decision-making process in order to change peoples’ mindset towards wildlife.

Freeland is one of those proactive organizations that adopts a multi-pronged approach.

Though often better known in the media as the creator of the WildScan app, Freeland is heavily involved in capacity building among local communities and seeks to change perceptions on a national scale throughout different countries.

“About 60 percent of the work that Freeland does focuses on creating awareness, reducing demand and behavior change campaigns,” said Pritchett.

Freeland works closely with local communities to raise awareness and teach youth to not consume wildlife. Photo courtesy of Freeland/Matthew Pritchett

“Together with leading wildlife conservation organizations in the region, we have started a large campaign called iTHINK,” he added.

Freeland, along with other organizations, created iTHINK as a campaign support platform. One of their first projects was in Bangkok. They set out to gather information from the public about their knowledge and enthusiasm for environmental issues. By essentially overloading city residents with banners, billboards and tv commercials, they were able to get a better sense of public interest.

Key opinion leaders and celebrities were also asked to participate in these media blitz events by recording messages of conservation and wildlife protection, which were then shown in high traffic areas. Surveys were subsequently conducted to gauge the public’s response and adjustments were made to later produce a more effective and thought-provoking campaign that would aid in changing the local mentality.

“We’ve actually been pretty successful,” said Pritchett. “Right now we’ve got it running in Thailand, Vietnam and China at the same time, and plans to expand iTHINK in those countries continue. Furthermore, within in a couple of years we are looking to expand iTHINK to other parts of the world with wildlife crime crises, including Africa and South America.

“The bottom line is Freeland truly believes in a completely holistic approach. We believe the best way to stop the mass slaughter of the world’s endangered animals for profit is to support law enforcement to increase arrests for enough time that behavior change campaigns like iTHINK can work and people no longer want to buy these animals or their products.”

Many song birds, including this Chattering lorry, are smuggled across the globe and sometimes very difficult for law enforcement officers to identify as protected or endangered. Photo courtesy of Freeland/Matthew Pritchett

The future of conservation

As organizations look toward crowd science and citizen involvement for help with conservation, it is becoming imperative for individuals to take part in protecting and improving the environmental landscape.

In this technology-driven world, people are more empowered than ever with apps and other tech-tools at their fingertips. Conservationists are calling for individuals to stop being bystanders and embrace the responsibility of being part of the solution. It is no longer enough to simply let law enforcement handle wildlife protection.

“If there is one thing I’d like to highlight,” Pritchett said, “it would be that everyone has a role to play in helping organizations like Freeland stop wildlife crime. Tell your friends not to buy wildlife, talk about it on social media and if you suspect wildlife crime, report it.”

Freeland’s WildScan app can be downloaded from Google Play for free and is available to anyone who has access to an Android device.