For Samia Mehrez, “Translating Egypt’s Revolution: The Language of Tahrir” is not a project that could be begun now. Most of the book’s chapters originated in her “Translating Revolution” class at the American University in Cairo last spring.

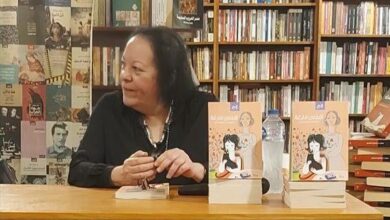

Mehrez, the head of the American University in Cairo’s Center for Translation Studies, discussed the book — published this month by AUC Press — after its launch Saturday evening. The chapters were authored by Mehrez, 10 members of the class and writer Menna Khalil, and edited by Mehrez.

Although the project went far beyond the classroom boundaries, Mehrez said it was motivated by the collective energy and commitment fostered within. That energy propelled them through many dark moments. It would be difficult to spark such enthusiasm for translating Egypt’s revolution now, she said.

Nonetheless, the downtown book launch was crowded with supporters and spectators. The book is an unusual collaboration between 12 people from very different linguistic, scholarly and cultural backgrounds. As Mehrez wrote in the introduction, the book was not crafted by a group of like-minded academics, but instead by “the poet, the musician, the technical translator, the journalist, the photographer, the security translator, the activist, the creative writer and the teacher.”

The group worked together, and discussions about various aspects of the work went on “late into the night,” contributor Laura Gribbon said at the launch.

“This project is very emotional for all of us,” said contributor Amira Taha.

Mehrez said that initially she had thought of writing such a book herself. However, she said that — as she was teaching the translation course last spring — it became “immediately obvious” that this was “not the moment for an individual” to take on such a project.

Mehrez emphasized, in the launch as in the book’s foreword, that the translations that came out of the project were a collective effort.

The eight essays are what Mehrez called “thick translations.” They are both translations of the “language of Tahrir” — its speeches and jokes, street art and poetry — and analyses of these translations.

Some of the chapters are too heavily descriptive; these rely on a discussion of creative production rather than on deep translation or analysis. Many of the book’s most successful chapters are those that use a framing metaphor, which itself works as a translation. This is the case in the chapters that overlay one image with another: the protests with traditional moulids, Egyptian political speeches with “performance” and myth making with the perceptions of Egypt’s army.

Perhaps the most thought-provoking chapter is the last — Sarah Hawas’ “Global Translations and Translating the Global,” which looks at how certain concepts were enacted in Egypt and then re-enacted in other linguistic and social imaginations: in Greece, in Israel, in Spain and in North America.

This chapter points toward the nature of translation as a multi-directional and many-stage process. What happens in Tahrir is continually translated and understood, or misunderstood, by influential speakers such as US President Barack Obama, whose translation is then repeated, echoed and re-translated in other contexts. In a new language and context, the once-Egyptian concepts become unrecognizable. Activists in Tel Aviv, for instance, stage a “Tahrir,” but theirs is a protest against certain economic policies, not a questioning of socio-political order.

This is because in creating a translation, Hawas writes, listeners often have a desire to “gravitate toward the familiar.” In so doing, she writes, listener-translators are often “silencing anything which is not” comfortable, thus “dismissing its potential to challenge power and to do so effectively.”

The meaning of the word “thawra” or “revolution” looks very different in Tahrir versus how it looks after it has been translated, familiarized and re-created into the words of, for instance, New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman.

The authors of “Translating Egypt’s Revolution” largely prioritized the politics of translation over its aesthetics. So, while the translations embedded in the text are generally interesting, they are not necessarily beautiful. Hawas said, during her presentation, that “these are open translations, and they should be read as artifacts.”

Both Hawas and Mehrez stressed the book’s emphasis on process and openness. This is, after all, a story that is still being told, and thus a translation that is still being written.

The book is now available from AUC Press for LE180. But, because it is a work “in progress,” it would be interesting to find it in other more accessible formats, in a space more open to continuing thoughts and contributions from these and other authors.