Copyright, as first envisioned, was a way to balance the rights of authors with the rights of their audiences. The public has a right to read both creative and academic works, and authors have a right to control aspects of their work and, perhaps, to earn a living.

But as others populated the space between author and reader, this relationship grew more complex. Publishers and other middlemen often took over managing authors’ rights. More books were well-produced, well-edited and attractive, but they were also priced out of the reach of many ordinary consumers. A parallel economy of illegal books sprang up, and powerful global coalitions were formed to stop them.

This has become a particularly thorny battle in Egypt, where public libraries are chronically understocked and in very short supply. In most cases, those who want to read a book must try to buy, borrow or copy it. Struggles have thus ensued between legal and “illegal” publishers.

Illegal copying is nothing new: It’s been a part of the Egyptian landscape ever since distinctions were made between legal and illegal book copying. But in the last year, with a combination of economic difficulties and the ease of digital copying, the issue has come more forcefully to Egyptian publishers’ doorsteps.

In recent months, the Egyptian Publishers Association has been working hard to promote its vision of copyright. During a two-day event that it called “Book Piracy and Author Copyright,” the association kicked off a high-profile attack on illegal book copying. Less than a week later, it announced that 18,900 illegal books had been seized.

The informal copying of books, as with other informal economic sectors, has grown rapidly in the last year. Photocopies of books can be found anywhere from universities to metro cars. For readers and authors, this has both ups and downs: For readers, it means flimsier products but better prices. For authors, it means smaller revenues but larger audiences.

For “legal” publishers, meanwhile, this has appeared to be a lose-lose situation. Their response has been to ask the government to clamp down on illegally copied books and on those who publish them.

However, Nagla Rizk, author of “Access to Knowledge in Egypt,” is urging publishers, authors and audiences to see things from a different angle.

“It is a waste of resources to continue to deal with [copyright infringement] from a policing perspective,” Rizk, who also heads the Access to Knowledge for Development Centre at the American University in Cairo, says.

The publishers’ association wants to convince the public that, for the good of writers and readers, illegal copying should not be tolerated. Association head Mohamed Rashad has called for greater penalties for copiers. Mohamed Salmawy, head of the Egyptian writers’ union, says the state needs to undertake raids on locations known to sell illegal books.

Rizk, on the other hand, says these efforts are a waste of both time and money.

“These resources would be better exercised in finding creative ways of remunerating the authors,” she says.

Rizk’s own book is “versioned.” The book, co-written with Lea Shaver, is available on Amazon for US$75 and in local bookstores for LE120. But, she says, it’s “also available free, legally free online.”

After all, Rizk says, books are expensive, and most Egyptian students are not wealthy. Also, new knowledge can only be created when there is access to existing works.

If Rizk were an Egyptian student, she says, and needed access to her research, “I can assure you that I would go and photocopy the whole book.”

This is not just an issue in Egypt. Around the world, authors, publishers and readers are working to define and redefine their rights. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights tries to address the needs of authors and readers. Article 27 states:

“(1) Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.”

This right is for all readers worldwide, regardless of their ability to pay. Article 27 also adds:

“(2) Everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.”

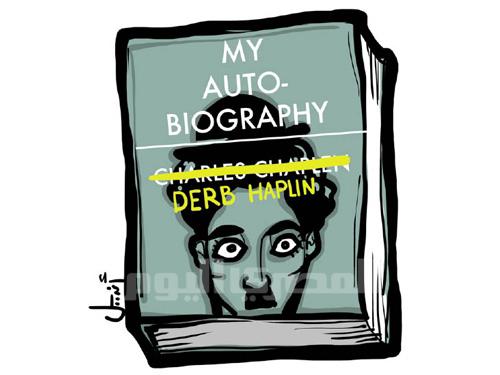

Lebanese writer and publisher Rania Zaghir, author of “Youmayyat Fikra Masrooka” (Diary of a Stolen Idea), addresses the formulation of authors’ moral rights.

“Moral rights,” Zaghir says, are such that “no one, including the publisher, has the right to change, alter [or] modify your work without your written approval.”

Rizk says no one really contests an author’s moral rights to his or her text. Authors should neither be plagiarized nor have their visions compromised. However, the landscape of material rights is more open to question. Who should pay for an author’s work, when and how much?

“Egypt is a special case, because quite a bit of Egypt’s culture relies on informality,” Rizk adds. Sharing and gift giving are very important in Egypt, she says. “If someone asks me to make a copy of my CD, which may by law be illegal, I will be happy to do it.”

Rizk advocates an approach to copyright law that takes into account the “needs and realities of the culture” rather than the top-down, one-size-fits-all approach of the internationally observed Berne Convention.

Zaghir, meanwhile, says she believes in a “middle ground” between traditional and new approaches to copyright.

“The real problem is that authors and illustrators, especially the novice ones … do not know their [existing legal] rights,” Zaghir says. “Only after this awareness is created, authors and illustrators can move on to more creative ways of publishing.”

These new methods are needed soon. Sharply restricting access to creative and intellectual works — whatever its benefits — has fed into an unhealthy cycle of less knowledge, fewer new works and fewer interested readers. New ways of sharing art and knowledge are needed in Egypt, now.