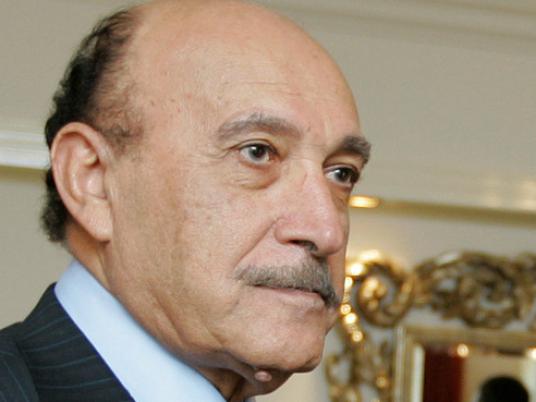

The scene of Omar Suleiman, Mubarak’s former intelligence chief, being escorted into the Presidential Elections Commission headquarters with the protection of military police on Sunday sent shock waves through both the revolutionaries who toppled Suleiman’s former boss a year ago and to Islamists who feel their grip on power is slowly slipping away.

While some believe the nomination and the possible success of Suleiman, who Mubarak appointed as vice president to shore up his rule when it was being challenged during the 18-day uprising, is tantamount to the revival of the old draconian regime. Many think it could spark another rebellion.

“This is not merely a counter-revolution; this marks the death of the revolution, or what [Suleiman] thinks is the death of the revolution. Having Suleiman in power means we will have to make another uprising,” said Yasser al-Hawary, an activist in the Youth for Justice and Freedom revolutionary movement.

Hawary was among the members of the opposition delegation that met with Suleiman when he was vice president during the early days of the revolution as part of the open dialogue called for by Mubarak during his last days in power.

“Suleiman was desperately defending Mubarak,” Hawary recounted.

Suleiman urged them not to insult the president and to save his face by accepting that he complete the six remaining months of his term, warning of a likely military coup if the president he left power right away, Hawary said.

The former head of the General Intelligence Services submitted his candidacy papers for the presidency on Sunday, 20 minutes before the door was closed to further nominations amid supporters’ chants of “The people want Suleiman for president.”

Suleiman surpassed the required 30,000 endorsement signatures from citizens across Egypt. Candidates running for president need to obtain 30,000 endorsements from citizens in 15 governorates or the support of 30 MPs.

Why did he run?

Suleiman denied his will to run for president during the revolution’s early days in February 2011, when he appeared on a TV interview done by ABC’s Christiane Amanpour.

“I don’t think so. I became an old man. I did a lot for the country and I have no ambition to be president of this country,” said Suleiman, after taking time to think about the answer.

But later, he claimed that he backtracked on his previous decision not to run because of strong popular demand.

“I cannot but meet the call and run in the presidential race despite the constraints and difficulties I made clear in my former statement,” he said in a statement Friday following a demonstration by hundreds of his supporters to persuade him to run.

However, this reason is quite unconvincing for Mohamed Qadry Saeed, military and technology adviser and head of the military studies unit at Al-Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies.

“I didn’t see the overwhelming masses that would persuade him to run for elections as [Suleiman] alleges,” Saeed told Egypt Independent. “He must have been pushed by the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces to make such a decision.”

Observers believe that the former vice president’s bid is related to the recent dispute between the Muslim Brotherhood and the military council that ensued after they allegedly failed to agree on a consensus candidate who would benefit both of their interests.

This feud has been primarily pronounced around the power-sharing dynamics, with the Brotherhood feeling increasingly that their control over Parliament alone is not enough without a share in the executive branch. The rift was most publicly articulated through the Brotherhood’s vehement demand to sack the military-appointed cabinet of Prime Minister Kamal al-Ganzouri.

Moreover, observers speak of the Brotherhood’s fear of the election of a president ahead of a constitutional arrangement that guarantees a mixed parliamentary and presidential system, which could endanger the current Parliament’s fate. From their side, the generals’ interests are often described as having a political arrangement that guarantees their safe exit from the presidency and the persistence of their political and economic immunity.

“Suleiman’s nomination reflects the widening gap between SCAF and the Brotherhood,” said Khalil al-Anani, a scholar at the Middle East Institute at Durham University and an expert on Islamist politics.

Anani said that when negotiations over a candidate reached a deadlock and it became evident to the Brotherhood that SCAF is not willing to genuinely hand over power to a civilian authority through seeking to maintain power behind the scenes, the Islamist group anticipated a strong reaction from SCAF — and that’s why it fielded Khairat al-Shater, its outgoing deputy supreme guide.

This is the first time in its history that the 84-year old organization will contest the highest executive authority in the country, in addition to claiming the majority of parliamentary seats in the recent elections, which is emblematic of their mounting power. This bodes ill with SCAF’s ambitions to maintain its heavy hand over power, forcing it to field Suleiman for the presidential election scheduled for 23 and 24 May, Anani said.

On the other hand, Bahey el-din Hassan, director of the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies, suggested a more politically intricate scenario that predates the Islamist-military feud. According to this scenario, Islamists, revolutionaries and liberals have been played by SCAF as pieces on a chessboard leading to the current situation.

Hassan argued that remnants of the Mubarak regime led by SCAF have been actually grooming Suleiman for the post a long time ago, even before the row between them and the Brotherhood came about.

“Someone in Suleiman’s position doesn’t just decide to run for elections days before the deadline for accepting nominations. This decision must be planned a long time based on prolonged deliberations with SCAF and [Ahmed] Shafiq [a presidential candidate who is also part of the military institution],” said Hassan, explaining that the Brotherhood responded by fielding their own candidates after discovering SCAF’s plan.

“The fluctuations reported in the media regarding Suleiman’s decision were meant to test the waters,” he added.

A third theory surrounds a conspiracy of a potential subtle agreement between the Brotherhood and SCAF over Suleiman’s candidacy. According to columnist Ahmed al-Sawy, the Brothers are only fielding candidates who stand to lose in the contest, which should give full legitimacy to Suleiman.

“The [Brotherhood] worked on dividing the revolutionary force from the beginning and on striking deals with the military, then on deliberately scaring society from it, in order for the silent majority of SCAF supporters and millions who strive for stability that has nothing to do with names and ideology to unite around a candidate from the heart of the old regime,” he wrote in Monday’s Al-Shorouk daily.

This multi-layered conspiracy, Sawy argues, goes back to the days when Suleiman sat down with the Brothers during the 18-day uprising to strike this deal days before the toppling of Mubarak.

Implications

Being the former intelligence chief, Suleiman played a key role in suppressing Islamists during Mubarak’s regime, as he is known to have personally overseen their torture in detention — which is why Anani predicted a tough confrontation between them in the election.

“The future is bleak and uncertain,” said Anani, who also envisaged a possible “radicalization of the Islamists’ youth in case Suleiman became the president.”

The Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party has nominated a second presidential candidate, party chairman Mohamed Morsy, in anticipation of Shater’s exclusion due to an outstanding sentence he received from a military court. Suleiman’s confirmation of his candidacy one day before prompted the group to take proactive measures, FJP sources told Al-Masry Al-Youm.

The FJP’s anxiety is justified, as Hassan believes that the path for Suleiman’s presidency was being paved during the past year. Recounting the events of the military-ruled transition period, Hassan argued that the orchestrated lack of security and the absence of serious steps to reform the oppressive police apparatus has forced the people to regard the restoration of security as a priority over any other calculations.

Last year was one of Egypt’s most turbulent years, with several bloody crackdowns on protesters by police and military forces, killing and injuring thousands, as well as the spread of street crime and dire economic conditions — providing reasons for average Egyptians to spurn protests and potentially look up to Suleiman.

Another discourse that was pushed through the media by SCAF was the fear of foreign conspiracies to infiltrate and divide Egypt, which was served by the legal case against the foreign-funded NGOs from the US and Europe, which were accused of implementing an external agenda.

“There is no one better than an intelligence or an army chief who is capable of restoring stability and protecting the country,” said Hassan.

Despite speculations that Islamists’ voting power is massive, measuring on the outcome of the parliamentary elections in which they secured about 70 percent of the seats, Hassan contends that Suleiman will cut from their constituency, because the above-mentioned reasons come as a priority for everyone, regardless of their ideological inclinations. Coupled with an already-divided Islamist constituency over four candidates with varying levels of conservatism, Suleiman’s success is closer than ever, added Hassan.

In addition, Amr Moussa — a candidate who also served in the Mubarak regime — doesn’t have the same patronage networks among public figures and corrupt businessmen as Suleiman does, as the former has been out of the local political scene for his 10 years as Arab League secretary general, said Anani.

However, Saeed downplayed Suleiman’s chances of success due to his lack of street popularity compared to Shafiq and Moussa, who had political posts in the past that brought them close to the people and have been working on organized campaigns for some time.

“Mubarak didn’t give him the chance to have a role in the public sphere. Although he was part and parcel of the regime, he was mainly working in the dark due to his sensitive role as the intelligence chief,” said Saeed.

On a different note, Anani considered Suleiman’s nomination an incentive for liberal and secular forces to unite on a pragmatic plan to stop the revival of the old regime by overcoming their dispute with the Islamists and possibly supporting an Islamist candidate, considering that they have the highest chances.

“It is definitely better than living with a military rule or that of the old regime,” said Anani.

Similarly, the revolutionary forces have been engaging in negotiations and discussions to consolidate their efforts toward the support of one candidate, such as Abdel Moneim Abouel Fotouh, a former Brotherhood leader who is considered the most moderate among Islamist candidates, said Hawary.

“The revolution can never die inside the heart of any true revolutionary, and everything that happens now only strengthens him and refuels his batteries,” Hawary said.