In what appears to be a last-ditch effort for the government to settle several high-dollar deals domestically instead of paying out millions in international arbitration proceedings, government officials recently designated a special office of the Investment Ministry to examine complaints and worries of Saudi investors.

The government is involved in arbitration proceedings precipitated by the recent nationalization of several privatized Saudi-owned companies.

Saudi citizen investments have yet to return to the state they were in before the 25 January revolution, though Saudi Arabia’s rulers have given a series of loans and aid to help keep the Egyptian government afloat during the interim period.

In June, the kingdom transferred US$1.5 billion as direct budget support, in addition to $430 million in project aid and offering $750 million credit for importing oil products.

Now, amid a serious effort to court international investment, President Mohamed Morsy’s government is promising to look after Saudi investors.

Investment Minister Osama Saleh told state-run news agency MENA last week that the ministry had set aside a new office that would work in conjunction with the Saudi Embassy to swiftly resolve investors’ problems and issues.

His announcement emerged after a visit from Saudi businessmen and leaders from the Council of Saudi Chambers delegation in mid-September.

“The Saudi delegation received assurances and indications for positive cooperation from the Egyptian side and at the highest levels of the Egyptian leadership to solve the problems of Saudi investors,” a press release from the Council of Saudi Chambers issued after the visit said.

The establishment of a specific office to address Saudi investors’ complaints is indicative of how much the government values Saudi money. No such office exists for any other foreign country.

Among Egypt’s largest investors, Saudis currently hold LE43 billion in capital in the country, according to the council, and own up to 2,500 companies diversified in varying sectors, such as tourism, petrochemicals and agriculture.

Egypt’s economic dependence on the kingdom also goes beyond investments.

Estimates of Egyptians working in Saudi Arabia range between 900,000 to 2 million. Saudi Arabia is the main destination for Egyptian emigrants, and foreign remittances from them are critical for many local families.

Contentious nationalization

Though Saleh did not mention the nature of the issues or the particular investors whom the committee would be dealing with, the committee will likely be tackling Egyptian courts’ decision to nationalize several high-profile Saudi-held assets.

Saudi investors are currently in international arbitration proceedings, looking for compensation for the nationalization of assets that were formerly, if briefly, theirs.

In September last year, after years of intermittent workers’ protests, the Administrative Court in Cairo ruled that the 2005 privatization of Tanta Flax and Oils Company, Misr Shebin El Kom Spinning and Weaving Company and Marageel Steam Company had been illegitimate, and the companies had been sold for cheaper than their market values.

Also, in October last year, former Agriculture Minister Salah Youssef issued a decree to seize Noubaria Seed Production Company and have its assets handed over to the Agriculture Ministry. The firm’s customers were told to redirect their payments to the ministry’s account.

Both Tanta Flax and Oils Company and Noubaria belonged to Saudi investor Abdallah Mohamed Saleh Kaki. The Tanta Flax case is still in arbitration.

The Kaki family acquired Alexandria-based Noubaria, an exporter of fruit and vegetables, in 1999, after former President Hosni Mubarak’s government chose to privatize the company because of its poor performance.

“The company was offered for sale in 1997 but to no avail due to lack of interest. Two years later, and after a bidding process between three international firms, the company was sold to Sheikh Abdallah Kaki in April 1999,” Mohamed Abdel Latif, the company’s former general manager, says.

Abdel Latif maintains that Noubaria was valued at stock price based on the year-end financials for 1997, and the sale was approved by three main governmental bodies: the Central Auditing Agency, the Holding Company for Agricultural Development, and the Higher Ministerial Committee for Privatization under former Prime Minister Kamal al-Ganzouri.

Under due course of the new management, Abdel Latif says, Noubaria prospered. The Saudi owners installed new machinery, increased exports, increased wages and offered employment openings — from 19 employees in 1997 to more than 1,000 employees as of now. The company quadrupled profits in a little over 10 years.

But the popular uprising that removed Mubarak from power also sparked an increase in labor organization and opposition. Labor leaders filed cases against the privatization of Tanta Flax and Oils and other companies, saying they treated workers unfairly and were given away for too little money.

Noubaria, meanwhile, was taken over by the Agriculture Ministry despite there being no judicial ruling ordering it.

“Army and police officers broke down the company doors, and confiscated 17 computers and all legal documents. Lands were seized, and crops were carried away and sold off at cheaper than their market price,” says Abdel Latif.

Kaki has entered international arbitration proceedings seeking compensation for Tanta Flax and Oils and Noubaria, asking for $350 million in damages.

“Our clients will be vigorously pursuing their rights against the Egyptian authorities and believe they will get a more impartial and objective hearing at an international level rather than a local level,” Robert Lambert, a partner at Clifford Chance, the UK law firm representing Kaki and the other investors, told the Abu Dhabi-based publication The National in March.

Calming fears of further nationalization

After the nationalization and other decisions under the previous transitional government, Morsy seems to be trying to return to good terms with Kaki and other Saudis with deep pockets, in part to avoid getting fleeced by arbitration courts.

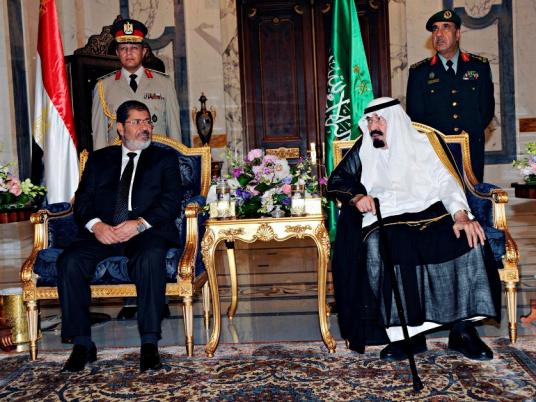

After being sworn into office, the president’s first official foreign visit was to Saudi Arabia.

Two months later, during the Council of Saudi Chambers delegation’s visit to the presidential palace, Morsy instructed his officials to thaw out all existing problems with Saudi investors, Al-Bowaba business news site reported.

“Possible annulment of privatization procedures” was the main problem facing Saudi investors, says Alaa Ezz, secretary general of the Federation of the Egyptian Chambers of Commerce, which hosted the Saudi delegation. “There was an obvious misinterpretation of privatization procedures on behalf of some government bodies.”

Ezz says the Saudi investors committee is not different from the Dispute Settlement Committee, which exists to resolve foreign investors’ complaints locally.

Saudi investors face the same problems as other international investors, he says, but due to the sheer size of some Saudi هnvestments and the significance of Egyptian-Saudi relations, the government deemed Saudis’ problems worthy of a specialized office at the Egyptian Investment Authority.

Reaching resolutions

The office for Saudi investors’ grievances already seems to have a fair amount of work ahead of it, but it remains to be seen whether Saudi investors will abandon the more lucrative international arbitration proceedings for local mediation.

“We worked out a matrix of the existing problems,” Ezz says. “Some were resolved immediately, while those still in court have to wait for legal procedures to ensue.”

"For example, Ezz says the Noubaria case had already been closed, as the public prosecutor declared the “legality of all sale constituents in the company’s privatization” in June 2008. However, other cases as Tanta Flax and Oil still remain in court."

The committee that examines the grievances, of which some members are judges, will operate mainly as a mediator between government bodies and foreign investors, Ezz says.

It will also have a large degree of autonomy and power.

Resolutions, once reached, can be immediately put into action, he says, as the body is both supervised and its decrees are coordinated through the Cabinet.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.