"Women's stories haven't yet been told,” said Afaf Alsayed, an Egyptian novelist and feminist who advocates for a more radical stance towards the position of women in Egyptian society. Alsayed was speaking at the fifth International Forum for the Arab Novel, which has been running in Cairo since Sunday under the theme “The Arab Novel… Where is it Going?”

Alsayed launched an ambitious project where young women from deeply conservative areas of the country such as Upper Egypt come together to learn how to tell and write their own experiences in a creative way. The goal is for the woman to "understand her pain though storytelling,” said Alsayed.

"It's storytelling that gives women their own existence,” Alsayed said. In her initiative to teach young women creative writing, “A large number of them [Upper Egyptian young women] were brave enough to address the ways in which they are being discriminated."

Despite the fact that Egyptian women in general are subjected to various means of discrimination in areas like employment and personal laws, challenges for Upper Egyptian women remain more severe than for women in other, less conservative parts of the country. In such geographical and cultural contexts of the southern part of the country, large numbers of women are denied the right to education, denied the right to work, denied the right to inherit agricultural land, and are subject to honor crimes and female genital mutilation (FGM).

In Upper Egypt the dominant scenes for women are of "inferiority, marginalization and alienation," said Alsayed.

She argued that the Salafi, whose way of thinking is more conservative toward the rights of women, saw Upper Egypt as a suitable environment to spread their ideas. "The Salafi thinking came and found the unchangeable nature of the existing roles of women and men and it was easier for them to exercise new forms of discrimination against women."

Those situations pushed young Upper Egyptian writers to write about their own difficult experiences, such as being refused an education and being forced into early marriages.

Another interesting component of the recent wave of storytelling from these women is that the "body,” according to Alsayed, is not portrayed as being shameful, as it is perceived by the conservative community.

"The body is against the siege," said Alsayed, who then traced some of the historical contexts for women as storytellers struggling to repossess representation of their own embattled bodies.

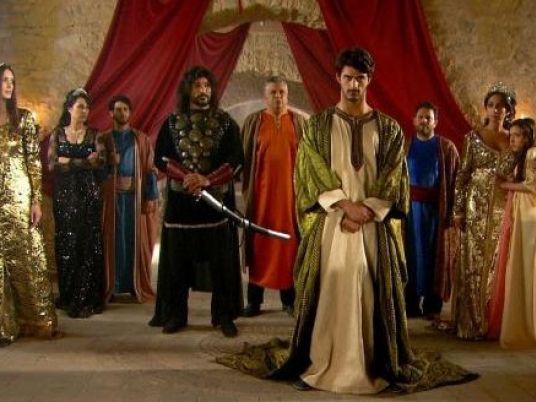

One of the main historical examples often used by Alsayed is Scheherazade, the talented storyteller of the legendary “One Thousand and One Nights.” Alsayed went further in exploring the ways in which the Persian queen was trying to change the course of history. “She was trying to revitalize the silent part of human history," said the novelist, adding that Shahryar (the Persian king) was the "bloody other" which Scheherazade was struggling against.

Alsayed elaborated that men, through their monopoly over the act of writing, have transformed woman from a real thing into a metaphor. Through Scheherazade's stories, women regained their position as a human. They are able to negotiate for and rescue themselves.

But the woman’s story does not end with “One Thousand and One Nights.” There are many other Scheherazades all throughout Egypt who are waiting to be able to take a stand and tell their story.