Several dog-eared issues of Al-Hilal magazine from the 1950s and 1960s came from Beirut to Cairo last week for Lebanese artist Marwa Arsanios’ workshop “Exercises in collective reading” at the Contemporary Image Collective. They are just here temporarily though – Arsanios will have to give them back soon to a friend in Lebanon. They’ve been on loan for a year and a half now.

Al-Hilal magazine was founded in 1892 by Jurji Zaydan, a Lebanese writer and a central figure of the Arab Renaissance, in Cairo. A monthly cultural magazine, it remained influential for decades despite major editorial shifts, including nationalization under former President Gamal Abdel Nasser. It is still produced today, but is now rather inconsequential.

“It was a semi-coincidence that I started this research,” Arsanios told an audience at CIC on Wednesday in a talk about exploring Al-Hilal. In 2010, 98 Weeks – a research project founded by Arsanios and Mirene Arsanios in Beirut that shifts its attention to a new topic every 98 weeks – began a research project called “On Publications.” Her friend then lent her a stash of old Al-Hilal magazines, which he had inherited from his grandfather at some point in the 1990s, in the midst of the fall of the Soviet Bloc, when he was 12 years old.

“Reading it was part of a specific culture in Beirut,” Arsanios said – it could be found in leftie, Communist circles.

98 Weeks organized a series of talks related to the content of the magazines. Issues had different themes, such as “The Intellectuals and the Revolution” (with Nasser on the cover), or “The Modernization of the Quran.”

A very critical talk was given by Al-Hayat newspaper editor and columnist Hazem Saghieh, who himself grew up during the golden age of pan-Arabism, on the August 1967 issue themed “Resistance.” Saghieh suggested that the magazine’s take on resistance was confused and propagandist, characteristics which caused Nasserism, despite increasing steps toward radicalization since the early 1960s and adherence to Soviet strategy since 1964, to hold on to private ownership, the family, and Islam. He also highlighted a romanticization of death as “happy martyrdom” that has a continuing legacy today in the region.

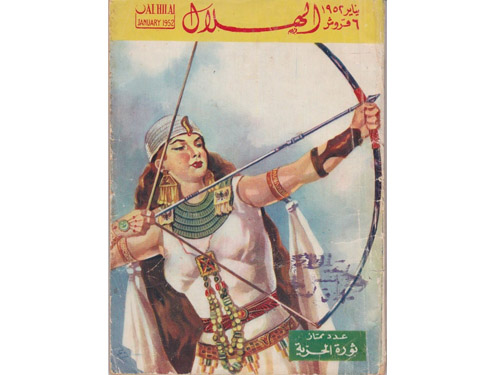

Lebanese novelist and journalist Rasha Al Atrash was another participant in the 98 Weeks series. She talked about the representation of women through three decades of Al-Hilal, having been surprised by women’s overwhelming presence on its covers. She found that its attitude toward women was also somewhat conflicted and propagandistic.

During the talks, 98 Weeks displayed the magazines. Arsenios said they “were trying to re-think them in the present tense” by having a diverse range of speakers offer their perspectives. The talks revealed a tendency in the writings from this optimistic time to sound naïve.

Arsenios has made other works involving Al-Hilal content, such as a lecture she gave wearing a costume made of strips of paper cut from copies of a section called “The News of Tomorrow and After Tomorrow.” The full-length costume almost covered the top of her head, and the talk therefore apparently sounded like mumbling. Another recent performance, called “Have You Ever Killed a Bear, or Becoming Jamila,” focused on women and socialism, questions on which, she said, often came together in Al-Hilal. While watching an actor playing the role of a female freedom fighter reading a story, people could look at the magazines.

This led to a project with Laurence Abu Hamdan, a London-based artist. They had been invited to participate in the most recent Jerusalem Show, an annual contemporary art festival in East Jerusalem. But they were not able to attend because they were Lebanese citizens. So they organized a marathon of three simultaneous five-hour collective readings, in Beirut, Ramallah, and Jerusalem, of Emile Habibi’s “The Pessoptimist,” a book Arsanios says is “very powerful in its political imagination.” A Candide-like Palestinian named Saeed is the main character, who having escaped Haifa for Lebanon in 1948, crossed illegally back to live in his now Israeli hometown.

“It became reading for the sake of reading,” Arsanios said of the marathon, unlike conventional reading groups which involve group reflection and learning.

Another literature-related performance Arsanios talked about was called “Carl and Olga, a Brief Encounter,” and grew out of a reading group on the writings of Karl Marx. She played her grandmother in an imaginary encounter with Marx in the downtown Cairo restaurant and bar Estoril.

For the workshop she is holding in Cairo, participants are choosing passages from the Al-Hilal stash to rewrite, and will then agree on a form in order to produce a collective text written together. “We will need to discuss all of that,” Arsanios said, “but that is the intention.”

The workshop started on 17 January and continues until 22 January. It is part of a program of library-related events and a project to create an online catalogue of Cairo’s art books, which is supported financially by the British Council. Other workshops under the same umbrella included one by Palestinian artist Shuruq Harb, and one by Irish photographer Ronnie Close, which led to the formation of a reading group that meets in the CIC library. There is also a forthcoming workshop by Lebanese-American photographer George Awde on coming of age and young people in Egypt at this historical moment.

While lots of artists visit Cairo, more often than not they are from Europe or America. One of the great things about talks by regional artists, though, is that they’re less likely to feel they should offer a take on what’s going on here or in the region. Also, audiences are more likely to get the references – critical talk of Arab Nationalist writings, for example, results in allusions that are inevitably more relevant here than nostalgic anecdotes about figures from the 1980s New York art scene.