A tirade launched by the Salafi Nour Party’s usually diplomatic and collected spokesperson Nader Bakkar against the president and the Muslim Brotherhood at large has revealed a deepening rift between Egypt’s main Islamist powerhouses.

The souring relations come at a critical time with parliamentary elections looming, prompting high-level officials on both sides to say individual disputes must be put aside and the focus placed on rebuilding the country.

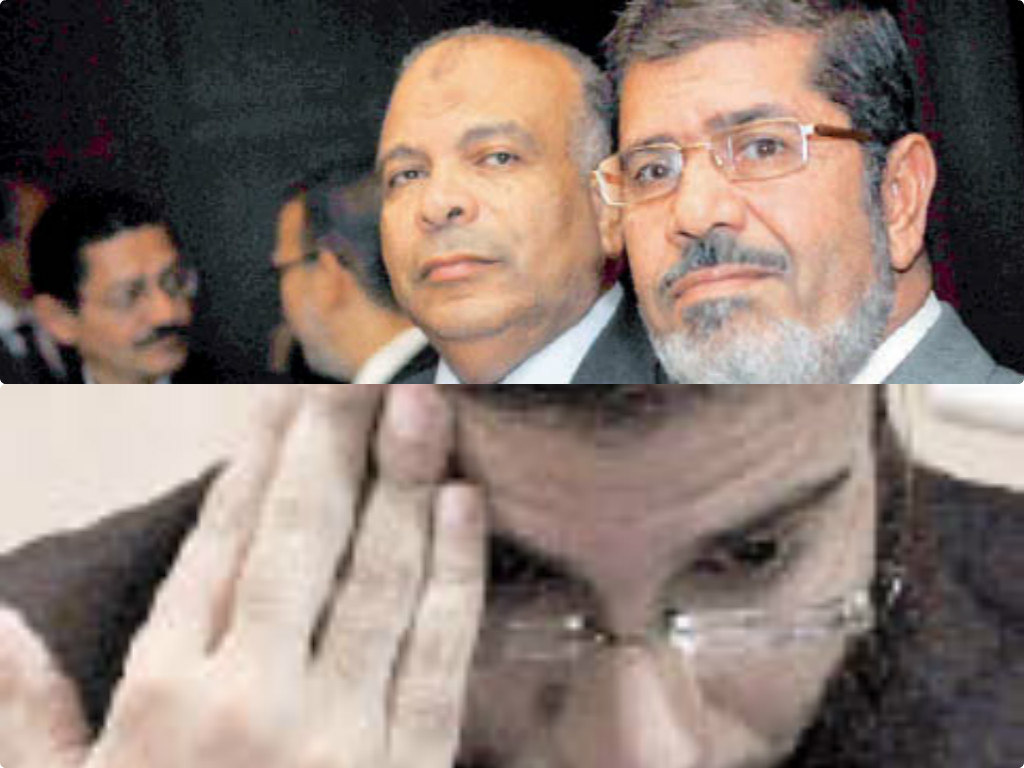

But the turbulent relationship between the Salafis and the Brotherhood suffered another blow Sunday night when President Mohamed Morsy dismissed his environmental adviser Khaled Alam Eddin of the Nour Party. The president apparently said he received reports that Alam Eddin was abusing his post for personal gain.

At a news conference Monday, an emotional Alam Eddin accused Morsy of defamation and demanded an apology, claiming the president sacked him because he refused to be a “puppet” and that he was openly critical of the Brotherhood-affiliated ruler.

During the same conference, Bassam al-Zarqa, another Nour Party leader and political adviser to the president, announced his resignation, leaving Morsy with a Brotherhood-dominated team of advisers, after his controversial November constitutional declaration triggered an earlier wave of resignations.

Earlier this week, Salafis called on the president’s office to present evidence against Alam Eddin. Khaled Saeed, a spokesperson for the Salafi Front, said if the accusations were true, Alam Eddin would be penalized by the party, the people and the law. On the other hand, he added, the president’s moral standing would permanently drop if his office couldn’t back up the allegations.

Meanwhile, Bakkar opened fire on the presidency and the Brotherhood in a Twitter rant. “If the presidency dismisses people based on suspicions and not investigations, then it might as well dismiss Yasser Ali, who has actually been summoned by prosecutors,” Bakkar wrote, suggesting the same for Aviation Minister Wael al-Maddawy, who was accused of hiring Morsy’s son for a job through nepotism.

Bakkar also alluded to Khairat al-Shater’s position in the Islamist movement and its political arm the Freedom and Justice Party. He also raised questions about FJP Vice President Essam al-Erian’s statements of “taping phone calls.”

He went as far as to say the president himself should step down on suspicion of the involvement of some subordinates in the killing of protesters — an area his Salafi party has long steered clear of commenting about.

Bakkar admits that while he has long criticized Morsy, his tone was exceptionally sharp following the sacking in light of “the president’s worsening performance.” “It has gone too far,” he tells Egypt Independent. “If you want to accuse [Alam Eddin] of something, you can file a complaint with the prosecutor general,” he says. Lamenting the presidential office’s lack of transparency, he urges Morsy to issue a clear apology.

The Nour Party has remained mum on the use of violence against protesters, which is why Bakkar’s statements came as a surprise to many. But Bakkar says he has been relentless in his criticism of the president’s office in several articles, citing his stance during the standoff between Morsy and the judiciary when former Prosecutor General Abdel Meguid Mahmoud was sacked.

“I criticized the president’s confused performance and stated that there were was an overlap in his advisers’ authorities,” he says.

Galal Mora, secretary general of the Salafi party, says, “Only the Nour Party knows what the Nour Party discusses and our stance toward the killing of protesters. We don’t always have to give statements to the press. The solution to any crisis is working on the ground, and the Nour Party has been doing just that.”

The unprecedented and bold attack on Morsy further complicates the relationship between the Brotherhood, from which he hails, and the Salafis, whose inconsistent attitude toward the ruling party raises questions.

The parties formed shortly after the 25 January uprising and were close to forming an electoral alliance in the 2011 parliamentary elections. However, they eventually decided to compete for seats separately, each banking on a broad and strong support base. Consequently, the FJP won 47 percent of the seats, while the Nour Party garnered 23 percent.

The fierce competition was palpable during the elections in 2011 and the short-lived parliament sessions themselves, he adds.

Having both won the majority of seats, the FJP and the Nour Party have repeatedly dismissed talks of an electoral alliance in the upcoming parliamentary elections.

In media statements, Nour Party Chairperson Younis Makhyoun said his party is in disagreement with the FJP, and that their “programs and views on managing the state are different.”

The Nour Party has also accused the Brotherhood of trying to “dominate” the country’s political scene and “monopolize” state institutions, a criticism also leveled by opposition bloc the National Salvation Front and protesters.

Earlier this week, the Nour Party joined forces with the liberal front since both agreed on the need for a Cabinet reshuffle and the replacement of new Prosecutor General Talaat Abdallah.

Last week, the Nour Party abstained from participating in a Brotherhood-organized rally dubbed “Together Against Violence,” saying it would only fuel the current political stalemate and do more harm than good.

However, both FJP and Nour Party members brush off ideas of an all-out rivalry, saying both parties should focus on rebuilding Egypt instead.

Ashraf El Sherif, a political science professor at the American University in Cairo, says the current standoff between the two is expected. The relationship between the Brotherhood and the Salafis at large is a “competitive” one, he says, as evidenced by the Salafis’ formation of its own, separate political party.

However, Azab Mostafa, a member of the FJP’s supreme authority, downplays any rift between the two. “Nour’s relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood is strong, based on coordination and alliances since before the revolution,” he says.

He adds Alam Eddin’s dismissal won’t have an effect on the relationship, saying both factions should focus on working toward a stronger Egypt. Regarding Bakkar’s statements, Mostafa says the Nour spokesperson should be held accountable for what he said as an individual.

“But the FJP is keen on keeping its relationship with the Nour Party at its best, especially during the coming period where we will be building Egypt,” he says. “The Nour Party is an addition to the FJP, not an adversary.”

Mora agrees, saying the main focus should be shifted to the current political impasse in Egypt, rather than the rift between the two Islamist groups, adding that they can “easily work things out through dialogue.”

Bakkar says that since “theoretically, we are supposed to distinguish between the president and the Muslim Brotherhood,” he will deal with the issue as a standoff with the president’s office alone.

The Nour Party will continue to criticize the administration, he adds, all the while maintaining its position as a mediator to find common ground between Morsy and his opposition.

Salafis have always been wary of a Brotherhood monopoly, Sherif says, which is why many supported former Brotherhood member Abdel Moneim Abouel Fotouh in the first round of the presidential elections.

“The Salafis are always worried about being excluded from the political as well as Islamist scene by the Muslim Brotherhood,” he says, adding that the two only join forces when there is a common agenda. Both parties had worked together to push for the ratification of a constitutional declaration in March 2011, under the rule of the military council.

The current dynamic is a far cry from the Nour Party’s solidly supportive stance during the controversy and tension surrounding Morsy’s constitutional declaration, as well as the draft constitution that was ratified in a snap referendum late last year. The Nour Party pushed for a “yes” vote to ratify a constitution drafted by an Islamist-dominated assembly.

At the time, Bakkar had said the president’s decisions were justified, and “it is clear to anyone following recent political events that there have been attempts to lead the country into a state of lawlessness.”

Bakkar had also called for pro-Morsy protests in Tahrir Square, where an ongoing sit-in had been in place against those very declarations. He was forced to retract his call following an online backlash and warnings of bloody clashes between opposing sides.

Sherif argues that the Nour Party recognizes the Brotherhood’s diminishing popularity and is choosing to distinguish itself from it. “They want voters to distinguish between them and the Muslim Brotherhood as the parliamentary elections loom. … They believe that the current standoff is not only justified, but is in the Nour’s best interest,” he says.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.