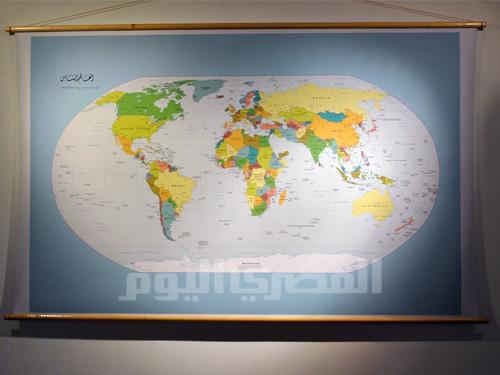

Remember the world map hanging on your classroom wall? You must have gathered around it with friends, trying to locate places you had heard of, read about, or were lucky enough to have travelled to. In fact, the first places people tend to search for, even as grown-ups, are those that they’ve visited. But what if you found that country to have disappeared? It’s that puzzlement that artist Osama Dawod plays on in his work “World Map,” part of the “Shift Delete 30” exhibition at Saad Zaghloul Center.

The artwork, a printout of a Photoshopped map with the Arabian Gulf countries erased, is a simple yet unconventional response to the show’s theme: a re-imagining of the past 30 years by 13 Egyptian artists who have added, deleted, and shifted things as they saw fit. All of the artists, born in the 1970s or 1980s, belong to the “Mubarak generation.”

Over the past year, we’ve been swamped with art responding to the ongoing revolution, from documentary photography to videos to straightforward text-based works. But very few have left a mark, and artists who have tried to develop longer-term projects have been constantly interrupted by the complex and fast-paced events of 2011. Few works stand out; Dawod’s “World Map” is one of them.

“I grew up listening to stories of my cousins and friends about their experience in the Gulf [countries],” says Dawod. Over the years, he realized how much of an impact the Gulf countries have had on Egypt in the past few decades. What struck him most were Arab rulers' offers of economic aid to Egypt on condition of Mubarak's release. “We need to rethink our relationship with that region, and know that we can live without them,” he explains, and the map helps explore that idea.

Another interesting work in the exhibition is Ahmed al-Samra’s “Angry Boys.” Samra introduced small changes to the “Angry Birds Peace Song” video by Finnish singer Osmo Ikonen to give new meaning to the story: The green little piggies steal the birds' eggs and fry them for their dinner with their king in “Sharm al-Sheikh.” As the angry birds set up their slingshot to fight the piggies for the eggs, they are drawn into violent confrontations, get injured, and call on the rest to join. In the segment entitled “Awaiting the sheep to join,” Samra adds footage of sheep running down from the back of a truck into the street, “recommending a different ending perhaps…” as the lyrics of the Christmas jingle suggests.

Also closely related to the challenges facing the ongoing revolution is Islam Kamal’s “The National Encyclopedia,” a 36-minute film showing young men and women practicing martial arts, interspersed with commentary from the media on recent events. The idea behind the work seems similar to that of the ongoing “Kazeboon” campaign, juxtaposing images with often nonsensical political commentary.

“Over time, people go numb when they see images of violence,” explains Kamal. But “The National Encyclopedia” is very raw in form, an attempt by Kamal to stay true to the online campaigns initiated by citizen journalists. In one scene, we see two youngsters practicing martial arts, while in the background we listen to a statement by Major General Hassan al-Roweiny on 23 July that triggered clashes between residents of Cairo's Abbasseya district and protesters heading to the Defense Ministry, resulting in scores of injuries.

Like others, Ibrahim Saad responded directly to the events of the past year in a didactic way. His multimedia installation, entitled “House of the Republic,” offers a collage of photographs from the 1989 Romanian revolution, along with footage of the street protests and a framed list of the reasons behind the revolution — most of which resonate with the Egyptian experience. Mostafa al-Banna’s timeline of the most significant events of the past three decades in Egypt cover the walls of the room, with footage from the Egyptian revolution shown on a screen at the center.

But these works weren’t the only ones reflecting a recent stir in the art scene. A few kilometers to the east of Saad Zaghloul Center, a group of 25 artists put on “Cairo Documenta 2” at Downtown’s Viennoise Hotel. In its second iteration, the exhibition presents a highly intriguing selection of works, although its original critique of art institutions seems to have waned somewhat.

Take, for instance, the untitled installation of Mahmoud Halawy, part of his “Foundation Defense” project. It comprises two framed works. The first is a fictitious clip from a Dutch magazine about the discovery of supernatural creatures in a sacred area in northern Siberia that humans cannot access; the second is an Autocad design of wall foundations. So many artists over the past decade have dealt with the phenomenon of gated communities for the rich surrounding the capital, but what’s unique about Halawy’s work-in-progress is its level of subtlety and reliance on myth to describe the relation between those living inside the residential compounds who feel a constant need to defend themselves and the public that wonders what it’s like inside.

This work could also be interpreted in relation to the current state of fear-mongering propagated by the ruling regime, tactically describing people who don’t fit the profile of the white-collar middle-class professional as “thugs.”

The media has played a large role in manipulating people and creating a scare, and last July, a group show entitled “Maspero” was devoted just to that idea. In “Cairo Documenta 2,” Ahmed Talal touches upon the issue in a simple yet intriguing way. In his painting series, he portrays TV aerials, a common scene on Egyptian rooftops. Yet it seems to the onlooker that they have been subtly metamorphosed into weapons.

Also playing on this idea of metamorphosis is Amr al-Kafrawy’s “Goddess of War.” The five prints show silhouettes of fantastical creatures evoking violence and war, morphed several times to reflect their various forms, faces and functions. The idea was triggered by the common scene of military tanks and soldiers over the past few months around the downtown area where Kafrawy lives. Looking at them more closely and how their meaning and the public perception of them changed over time, Kafrawy chose them as the starting point for his work that unpacks the mythical idea that “war goddesses are superior to the civilians they protect,” explains the artist. The prints seem almost like puppets in a shadow theater; in fact, turning them into a play will be the next step in Kafrawy’s project.

Much of the work in the two exhibitions deals with the revolution, but instead of earlier celebratory works, these reflect the state of unfinishedness that we feel. Perhaps what captures this most strongly is Jasmina Metwally's installation at “Cairo Documenta 2.” Entitled “About a Donkey that Wanted to Become a Painting,” the work juxtaposes a video image of a donkey lying dead on the side of a road in Fayoum with a fragment of a painting of the same donkey and an empty canvas painted in yellow, with small traces of dust and decay. “They’re fragments of things that I’ve been surrounded by recently, still trying to compose something out of them, make them work together.”

“Shift Delete 30” is shown until 30 January at Saad Zaghloul Center, 2 Saad Zaghloul Street, Sayeda Zeinab. And “Cairo Documenta 2” is on until 28 January at the Viennoise Hotel on Mahmoud Basiony Street, downtown Cairo.