“When our mom passed away ten years ago in Rome, we thought it was natural to take her back home,” says Francesco Monaco as he walks around the Catholic Cemetery in Alexandria. At the edge of the central Chatby neighborhood, behind the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, lie four graveyards of the size of ten soccer fields, where over 100,000 Armenians, Greeks and Italians, who populated a quarter in the city for a century until 1960, are buried.

The tombs have been neglected with few descendants left to bring fresh flowers.

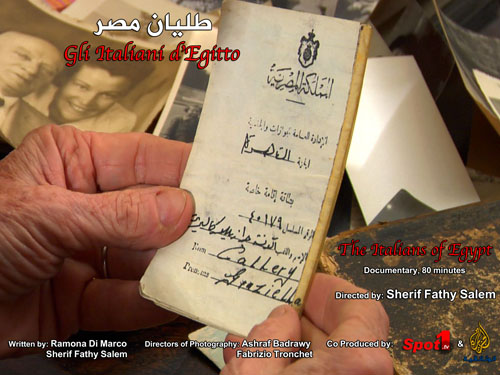

Monaco, and six other Italian men and women who Sherif Fathy follows in his latest documentary, are among those few. In “The Italians of Egypt,” he reconstructs an intimate story of families, friendships and work when the cultures and destinies of the two countries seemed closely tied, and how political changes over the past 50 years have changed the lives of the migrants.

We learn about Carlo Meratti, for instance, who founded the first postal company in Egypt in 1820, and we learn that Italy’s last king, Vittorio Emanuele, died in Alexandria as an exile, the same way King Farouk died in Rome.

Ahmed Abu Zeid, former dean of the University of Alexandria who was interviewed as an expert and witness to those years, remembers, “We were used to hearing many different languages on the street when we were kids. It was normal.”

World War II and the 1952 Revolution, which interrupted those apparently idyllic years, caught the Italians, like other foreign communities, in the middle of the conflicts. Hence they began their withdrawal from the country. Things got more complicated as some came to represent “problematic” and overlapping identities: 14 percent of Jews in Egypt had Italian origins, and rabbis were usually Italian. Others were fascists or sympathizers of fascism. And some simply saw themselves as Egyptians with Italian origins that would never support Egypt’s enemies. But they were in the wrong place at the wrong time, like architect and chief of Islamic Endowments Mario Rossi, who designed the famous Al-Morsy Abu al-Abbas Mosque in Alexandria and the Omar Makram Mosque in Cairo. He ended up in a concentration camp.

Historians in the film show us that the Italian and Egyptian national identities at the time were still developing and influenced by one another to the point that the Young Egypt Party’s green shirts got their inspiration from Mussolini’s black shirts.

“We fell in love with this young idea of Italy,” says 90-year old Yolanda Battigelli. “But we have to admit that to be Italian meant to be fascist… even schools were fascist. You had no choice.”

“We were fascinated by fascism because we didn’t have our own identity. Our families had migrated before Italy was united. So fascism felt like a celebration here. We didn’t fear the persecutions,” she adds, before showing a postcard her father sent on her 18th birthday from the concentration camp in Fayed in the Suez Canal area.

“It was not so sad after all… We [the Italians] recreated a small city inside the camp,” says Mr. Bicchi, a painter and heir of the renowned Bicchi School of Painting. “I was famous for my work and I made portraits for the British colonels in jail,” he says while laughing. “I made enough money to buy a Topolino car when I came out.”

The film is full of anecdotes that highlight the positive attitude of some of the “Awlad Misr” (Children of Egypt) generation, who grew up and still live in Egypt despite the massive transformations the country underwent.

“[To us] Egypt was like America,” says one community member.

Waves of migration from Italy to Egypt, as we learn from Fathy’s documentary, were mostly far from the stereotypical images of poverty and manual labor. It was rather a bourgeois migration of intellectuals, architects, artists, businessmen and craftsmen, to a country with very similar traditions, values and lifestyles.

The film’s narration focuses on this sense of solidarity and peace that emerged within the community, leaving controversial blind spots of history aside. As one audience member pointed out during the discussion that followed the screening last week at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, there are no stories of mixed marriages, suggesting that the stability of coexisting also depended on respecting diversity while also being separated.

One character in the film says, “We hardly talked about religion at all. It was considered inappropriate to question one’s beliefs.”

“The Italians of Egypt,” which is co-produced by Al-Jazeera Documentary and Fathy and his wife Ramona Di Marco’s company, Spot1 TV, is the result of two years of research undertaken by Fathy and Di Marco. The couple’s personal experience of living and working between Italy and Egypt seems to have encouraged them to dig into the histories of their respective countries of origin and choice. Fathy previously also made two related documentaries: “The New Italians,” which focuses on the second generation of Egyptian migrants to Italy, and “The History of Sicilian Muslims.”

The audience at the screening, mostly people affiliated with the surviving Italian community in Egypt, welcomed the film with enthusiasm. There was an informal atmosphere of family reunion. But even those not related to the Italians of Egypt welcomed the gesture. One audience member said, “All Egyptians should be aware of this. It’s our history. I’m 19 years old and had no idea about all this.”

Documentary films in Egypt are seldom rewarded with a good distribution, and their educational value is rarely built upon. They remain only in the memory of groups of audiences, often already interested in the topic.

Battigelli hoped in the film that one day people “would remember me and tell my story.” They might, if the film itself, like many others and the faded photos the characters show, doesn’t end up forgotten in a dusty archive for another 50 years.